Stimulated emission

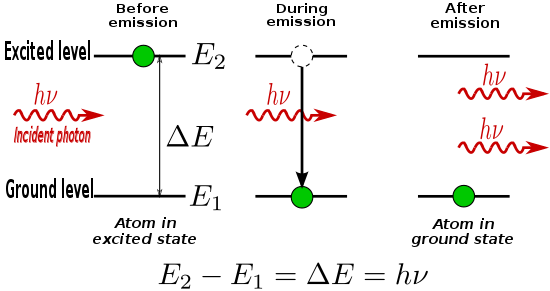

Stimulated emission is the process by which an incoming photon of a specific frequency can interact with an excited atomic electron (or other excited molecular state), causing it to drop to a lower energy level.

This is in contrast to spontaneous emission, which occurs at a characteristic rate for each of the atoms/oscillators in the upper energy state regardless of the external electromagnetic field.

According to the American Physical Society, the first person to correctly predict the phenomenon of stimulated emission was Albert Einstein in a series of papers starting in 1916, culminating in what is now called the Einstein B Coefficient.

[1][2][3][4] The process is identical in form to atomic absorption in which the energy of an absorbed photon causes an identical but opposite atomic transition: from the lower level to a higher energy level.

However, when a population inversion is present, the rate of stimulated emission exceeds that of absorption, and a net optical amplification can be achieved.

Lacking a feedback mechanism, laser amplifiers and superluminescent sources also function on the basis of stimulated emission.

Electrons and their interactions with electromagnetic fields are important in our understanding of chemistry and physics.

However, quantum mechanical effects force electrons to take on discrete positions in orbitals.

When an electron is excited from a lower to a higher energy level, it is unlikely for it to stay that way forever.

When such an electron decays without external influence, emitting a photon, that is called "spontaneous emission".

A material with many atoms in such an excited state may thus result in radiation which has a narrow spectrum (centered around one wavelength of light), but the individual photons would have no common phase relationship and would also emanate in random directions.

An external electromagnetic field at a frequency associated with a transition can affect the quantum mechanical state of the atom without being absorbed.

In response to the external electric field at this frequency, the probability of the electron entering this transition state is greatly increased.

[5][6] Stimulated emission can also occur in classical models, without reference to photons or quantum-mechanics.

According to physics professor and director of the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms Daniel Kleppner, Einstein's theory of radiation was ahead of its time and prefigures the modern theory of quantum electrodynamics and quantum optics by several decades.

Alternatively, if the excited-state atom is perturbed by an electric field of frequency ν0, it may emit an additional photon of the same frequency and in phase, thus augmenting the external field, leaving the atom in the lower energy state.

The rate of emission is thus proportional to the number of atoms in the excited state N2, and to the density of incident photons.

The B coefficients can be calculated using dipole approximation and time dependent perturbation theory in quantum mechanics as:[9][10]

Einstein showed from the form of Planck's law,[citation needed] that the coefficient for this transition must be identical to that for stimulated emission:

Thus absorption and stimulated emission are reverse processes proceeding at somewhat different rates.

In order for this to be a positive number, indicating net stimulated emission, there must be more atoms in the excited state than in the lower level:

is known as a population inversion, a rather unusual condition that must be effected in the gain medium of a laser.

The notable characteristic of stimulated emission compared to everyday light sources (which depend on spontaneous emission) is that the emitted photons have the same frequency, phase, polarization, and direction of propagation as the incident photons.

the strength of stimulated (or spontaneous) emission will be decreased according to the so-called line shape.

Considering only homogeneous broadening affecting an atomic or molecular resonance, the spectral line shape function is described as a Lorentzian distribution

The population inversion, in units of atoms per cubic metre, is where g1 and g2 are the degeneracies of energy levels 1 and 2, respectively.

Grouping the first two factors together, this equation simplifies as where is the small-signal gain coefficient (in units of radians per metre).

We can solve the differential equation using separation of variables: Integrating, we find: or where The saturation intensity IS is defined as the input intensity at which the gain of the optical amplifier drops to exactly half of the small-signal gain.

The general form of the gain equation, which applies regardless of the input intensity, derives from the general differential equation for the intensity I as a function of position z in the gain medium: where

To solve, we first rearrange the equation in order to separate the variables, intensity I and position z: Integrating both sides, we obtain or The gain G of the amplifier is defined as the optical intensity I at position z divided by the input intensity: Substituting this definition into the prior equation, we find the general gain equation: In the special case where the input signal is small compared to the saturation intensity, in other words, then the general gain equation gives the small signal gain as or which is identical to the small signal gain equation (see above).