Attrition warfare against Napoleon

[2][3] On 11 October 1810, Massena with 61,000 men found Wellington behind an almost impenetrable defensive position, the Lines of Torres Vedras consisting of forts and other military defences built in absolute secrecy to defend the only path to Lisbon from the north.

[4] The lack of food and fodder meant that Masséna was forced to retreat northwards, starting on the night of 14/15 November 1810, to find an area that had not been subjected to the scorched earth policy.

The French held out through February although the Iberian peninsula had suffered one of the coldest winters it had ever known, but when starvation and diseases really set in, Masséna ordered a retreat at the beginning of March 1811 having lost another 21,000 men.

On 7 September 1812, Napoleon with 115,000 men found Kutuzov in Borodino in a bad defensive position blocking the only path to Moscow from the west.

But Napoleon was forced to retreat, starting on the 19 October 1812, and tried to find southwards an area that had not been subjected to the scorched earth policy.

[6] The constant retreat of the Russian Army in the beginning of the war forced Napoleon to rapid marches in great heat to catch up with them.

During the constant retreat from Moscow to Poland of the Grande Armée, Kutuzov with his main army avoided following Napoleon directly.

Kutuzov escorted the Grande Armée on parallel roads in unspoilt regions of the south thus saving great parts of his army.

It was a rebellion by the people of Madrid against the occupation of the city by Napoleon's troops, provoking repression by the French Imperial forces using the Mamelukes of the Imperial Guard of Napoleon to fight residents of Madrid wearing turbans and using curved scimitars, thus provoking memories of the Muslim Spain.

[9] In the Patriotic War of 1812, Lieutenant-Colonel Denis Davydov suggested to his general, Pyotr Bagration to attack the supply trains of Napoleon's invading Grande Armée with a small force.

The guerrilla fighters tied down large numbers of French troops over a wide area with a much lower expenditure of men, energy, and supplies.

After probing the Lines of Torres Vedras in the Battle of Sobral on 14 October, Masséna found them too strong to attack and withdrew into winter quarters.

Using the reverse slope, as he had many times in the Peninsular War, Wellington concealed his strength from Napoleon, with the exception of his skirmishers and artillery.

3 May 1811: When he eventually returned to Spain in April 1811 and before he fought the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, he had lost a further 21,000 men, mostly from starvation, severe illness and disease.

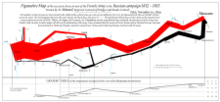

[16] To estimate the attrition rate caused by the Russian Fabian strategy, the numbers of soldiers of the Grande Armée are roughly taken from Minard's Map that were based on French sources.

26 June 1812, 3rd bulletin: The Grande Armée had crossed the Neman River supported by logistics based on water transport of food for the troops up to Wilna, consisting mainly of flour, brandy and biscuit.

[22] The first main problem for the French army was the feeding of the horses as it was not possible to find enough fodder in sufficient quality for all of them as they passed a poor countryside.

As the speed of the supply trains had to be higher than that of the marching army, the transport from Wilna to the advancing troops nearly collapsed because of the bad roads and the decreasing number of horses.

[24] The forage expeditions of the Grande Armée and now in growing number its lawless deserters increased the hatred of the poor peasants preparing the emotional ground for a merciless people's war.

The young, inexperienced conscripts were not used to live off the land that already had been devastated by the retreating Russian army and a second time by their own leading French troops like the Guard.

[34] 10 September 1812, 18th bulletin: After the lost Battle of Borodino the Russian army opened the road to Moscow for the Grande Armée.

He increased the guerrilla warfare of the Cossacks and the people's war of the peasants slowly weakening the French army.

His own army was reinforced with men, horses, weapons, ammunition, food, fodder and water, warm clothes and boots from the rich south of Moscow.

[18] The Grande Armée did not forge caulkined shoes for all horses besides the experienced Polish cavalry to enable them to walk over roads that had become iced over.

The detour enforced a delay of a couple of days until he reached the road to Smolenzk that his own Grande Armée had cleaned from anything useful on the way to Moscow.

Many soldiers without a fur, heavy boots and food but loaded with loot died of cold and fatigue and the standard night bivouac without a protecting tent became a death trap.

A lot of French soldiers died by starvation as no supply was available and foraging was extremely dangerous because of the peasants and the large distances to be covered to find anything in the devastated landscape.

In the thinly populated areas of Russia the lack of food and water in combination with extreme temperatures and the Russians' scorched earth strategy led to a catastrophe that was ignored by Napoleon.

[55] The guerilla warfare of the Cossacks against supply trains implicitly led to the death of many soldiers and their horses as they were forced to eat and drink from contaminated sources, exposing thousands to disease.

The army was simply unable to raise the vast amount of supplies needed by foraging in the poor and devastated Russian countryside against a cruel people's war.