Cossacks

They inhabited sparsely populated areas in the Dnieper, Don, Terek, and Ural river basins, and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of both Ukraine and parts of Russia.

[12][16] It is unclear when people other than the Brodnici and Berladnici (which had a Romanian origin with large Slavic influences) began to settle in the lower reaches of major rivers such as the Don and the Dnieper after the demise of the Khazars.

Cossacks such as Stenka Razin, Kondraty Bulavin, Ivan Mazepa and Yemelyan Pugachev led major anti-imperial wars and revolutions in the Empire in order to abolish slavery and harsh bureaucracy, and to maintain independence.

By the end of the 16th century, they began to revolt, in the uprisings of Kryshtof Kosynsky (1591–1593), Severyn Nalyvaiko (1594–1596), Hryhorii Loboda (1596), Marko Zhmailo (1625), Taras Fedorovych (1630), Ivan Sulyma (1635), Pavlo Pavliuk and Dmytro Hunia (1637), and Yakiv Ostrianyn and Karpo Skydan (1638).

For the Muscovite tsar, the Pereiaslav Agreement signified the unconditional submission of his new subjects; the Ukrainian hetman considered it a conditional contract from which one party could withdraw if the other was not upholding its end of the bargain.

Accordingly, he concluded a treaty with representatives of the Polish king, who agreed to re-admit Cossack Ukraine by reforming the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to create a third constituent, comparable in status to that of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The native land of the Cossacks is defined by a line of Russian town-fortresses located on the border with the steppe, and stretching from the middle Volga to Ryazan and Tula, then breaking abruptly to the south and extending to the Dnieper via Pereyaslavl.

[72] The Don Cossack Host (Russian: Всевеликое Войско Донское, Vsevelikoye Voysko Donskoye) was either an independent or an autonomous democratic republic, located in present-day Southern Russia.

The government's efforts to alter their traditional nomadic lifestyle resulted in the Cossacks being involved in nearly all the major disturbances in Russia over 200 years, including the rebellions led by Stepan Razin and Yemelyan Pugachev.

[78]: 52 The Code increased tax revenue for the central government and put an end to nomadism, to stabilize the social order by fixing people on the same land and in the same occupation as their families.

[82] By the 19th century, the Russian Empire had annexed the territory of the Cossack Hosts, and controlled them by providing privileges for their service such as exemption from taxation and allowing them to own the land they farmed.

In 1840, the Cossack hosts included the Don, Black Sea, Astrakhan, Little Russia, Azov, Danube, Ural, Stavropol, Mesherya, Orenburg, Siberian, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseisk, Irkutsk, Sabaikal, Yakutsk, and Tartar voiskos.

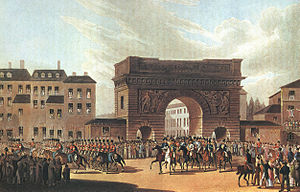

[83] Increasingly as the 19th century went on, the Cossacks served as a mounted para-military police force in all of the various provinces of the vast Russian Empire, covering a territory stretching across Eurasia from what is now modern Poland to the banks of the river Amur that formed the Russian-Chinese border.

The need for the government to call up Cossack men to serve either with the Army or a mounted police force caused many social and economic problems, which compounded by the growing impoverishment the communities of the Hosts.

Although they comprised only a fraction of the 300,000 troops in the proximity of the Russian capital, their general defection on the second day of unrest (10 March) enthused raucous crowds and stunned the authorities and remaining loyal units.

[101]: 112–120 In the Russian Far East, anticommunist Transbaikal and Ussuri Cossacks undermined the rear of Siberia's White armies by disrupting traffic on the Trans-Siberian Railway and engaging in acts of banditry that fueled a potent insurgency in that region.

In late 1918 and early 1919, widespread desertion and defection among Don, Ural, and Orenburg Cossacks fighting with the Whites produced a military crisis that was exploited by the Red Army in those sectors.

Although hostile to communism, the Cossack émigrés remained broadly divided over whether their people should pursue a separatist course to acquire independence or retain their close ties with a future post-Soviet Russia.

[115]: 110–126, 150–169 In late 1943, the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories and Wehrmacht headquarters issued a joint proclamation promising the Cossacks independence once their homelands were "liberated" from the Red Army.

[99]: 252–254 In early May 1945, in the closing days of WWII, both Domanov's "Cossachi Stan" and Pannwitz's XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corps retreated into Austria, where they surrendered to the British.

Many Cossack accounts collected in the two volume work The Great Betrayal by Vyacheslav Naumenko allege that British officers had given them, or their leaders, a guarantee that they would not be forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union,[116] but there is no hard evidence that such a promise was made.

At the end of the month, and in early June 1945, the majority of Cossacks from both groups were transferred to Red Army and SMERSH custody at the Soviet demarcation line in Judenburg, Austria.

The movement supported the re-establishment of the Hetman state of Pavlo Skoropadskyi and devoted a lot of energy to military training of Ukrainian emigrés for the future liberation of their homelandgoing as far as to acquire a number of airplanes.

[120] The journalist Hal McKenzie described Nazarenko as having "cut a striking figure with his white fur cap, calf-length coat with long silver-sheathed dagger and ornamental silver cartridge cases on his chest".

The American journalist Christoper Simpson in his 1988 book Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War called Nazarenko a leading Republican activist who made "explicit pro-Nazi, anti-semitic" statements in his speeches.

In 1654, when Macarius III Ibn al-Za'im, the Patriarch of Antioch, traveled to Moscow through Ukraine, his son, Deacon Paul Allepscius, wrote the following report: All over the land of Rus', i.e., among the Cossacks, we have noticed a remarkable feature which made us marvel; all of them, with the exception of only a few among them, even the majority of their wives and daughters, can read and know the order of the church-services as well as the church melodies.

[137] In the literature of Western Europe, Cossacks appear in Byron's poem "Mazeppa", Tennyson's "The Charge of the Light Brigade", and Richard Connell's short story "The Most Dangerous Game".

In marked contrast the two Caucasian hosts (Kuban and Terek) wore the very long, open-fronted, cherkesska coats with ornamental cartridge loops and coloured beshmets (waistcoats).

[148] The Combined Cossack Guard Regiment, comprising representative detachments from each of the remaining hosts, wore red, light blue, crimson, or orange coats, according to squadron.

French propaganda portrayed the inhabitants of the Scottish Highlands as barbarian with non-human bodily functions, who allegedly felt great joy when destroying civilian housing, farmland, and even entire human settlements.