Aubrey holes

25 of the pits contained later cremation burials inserted into their upper fills along with long bone pins which may have secured leather or cloth bags used to hold the remains.

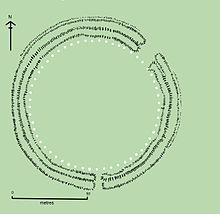

The holes are in an accurate, 271.6m circumference circle, distributed around the edge of the area enclosed by Stonehenge's earth bank, with a standard deviation in their positioning of 0.4m.

[citation needed] That sarsen stone chips have only been found in the upper fills of the excavated pits implies that the digging of the holes predates the megalithic phases of Stonehenge.

It was formerly thought that when the Aubrey holes were first dug, the only standing feature at Stonehenge was the Heelstone, which marked the point of the midsummer sunrise, viewed from the centre of the henge.

In a survey of twentieth-century excavations at Stonehenge, English Heritage's Stonehenge in its landscape, archaeologist Karen Walker collated and studied the surviving records from all the earlier work on the holes and concluded that "Although the evidence is inconclusive, and will no doubt be the subject of continued debate, the authors are inclined to support the view that the Aubrey Holes held posts, which were removed, rather than burnt in situ or left to decay.

An early attempt to analyse the positions of the Aubrey holes was undertaken by Gerald Hawkins, a professor of astronomy at Boston University in the 1960s, using an IBM 7090 computer.

As the motion of the Moon's orbit also causes it to work its way across the sky on an 18.61 year cycle in what is known as the journey between major and minor standstill and back, the theory that this period was both measurable and useful to Neolithic peoples seemed attractive.

Lunar movements may have had calendrical significance to early peoples, especially farmers who would have benefited from the division of the year into periods which indicated the best times for planting.

Hawkins argued that the Aubrey Holes were used to keep track of this long time period and could accurately predict the recurrence of a lunar eclipse on the same azimuth, that which aligned with the Heel Stone, every 56 years.

Going further, by placing marker stones at the ninth, eighteenth, twenty-eighth, thirty-seventh, forty-sixth and fifty sixth holes, Hawkins deduced that other intermediate lunar eclipses could also be predicted.

More recent examination, notably by Richard Atkinson, has proved Hawkins largely wrong,[citation needed] as it is now established that the different features at the monument that he tried to incorporate into many of his alignment theories were in use at different times and could not have worked alone, the lateness of the installation of the Heel Stone being the final nail in the coffin.

[citation needed] Furthermore, the 56-year period is not in fact a reliable method of predicting eclipses and it is now accepted that they never repeat their date and position over three consecutive 18.61 year-long lunar cycles.

It has also been pointed out by R. Colton and R. L. Martin that simpler methods exist, based on observing the position of each moonrise, which would have worked just as well and which would not require moving numerous markers amongst 56 holes.

According to the astrologers Bruno and Louise Huber the Aubrey holes were an astronomical abacus to mark the positions and calculate the movement of lunar nodes.

In fact, early Stonehenge may have been barely different from the other Neolithic timber circles of the British Isles, which had varying numbers of postholes and orientations and could therefore not have been used for in island-wide eclipse predicting.

The interpretation of such timber circles is unclear, although parallels were drawn with Native American totem poles by Stuart Piggott in a 1946 BBC radio lecture.

[citation needed] Another possible explanation for the holes, suggested by Richard Atkinson, is that they were excavated in turn in some unknown ritual involving a procession around the inside of the monument.