Augmentative and alternative communication

During the 1960s and 1970s, spurred by an increasing commitment in the West towards the inclusion of disabled individuals in mainstream society and emphasis on them developing the skills required for independence, the use of manual sign language and then graphic symbol communication grew greatly.

Message generation through AAC is generally much slower than spoken communication, and as a result rate enhancement techniques have been developed to reduce the number of selections required.

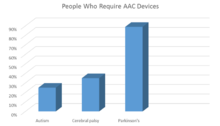

[13] Prevalence data vary depending on the country and age/disabilities surveyed, but typically between 0.1 and 1.5% of the population are considered to have such severe speech-language impairments that they have difficulty making themselves understood, and thus could benefit from AAC.

For example, the Amer-Ind code is based on Plains Indian Sign Language, and has been used with children with severe-profound disabilities, and adults with a variety of diagnoses including dementia, aphasia and dysarthria.

[22][29] Sign languages require more fine-motor coordination and are less transparent in meaning than gestural codes such as Amer-Ind; the latter limits the number of people able to understand the person's communication without training.

[32] Communication books and devices are often presented in a grid format;[58] the vocabulary items displayed within them may be organized by spoken word order, frequency of usage or category.

[71] AAC evaluations are often conducted by specialized teams which may include a speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, rehabilitation engineer, physiotherapist, social worker and a physician.

[95][96] Several reviews have found that the use of AAC does not impede the development of speech in individuals with autism or developmental disabilities, and in fact, may result in modest gains being observed.

[99] Researchers hypothesize that using an AAC device relieves the pressure of having to speak, allowing the individual to focus on communication, and that the reduction in psychological stress makes speech production easier.

[117] Depending on the location of the brain lesion, individuals with cerebral palsy can have a wide variety of gross and fine motor challenges, including different forms and areas of the body affected.

[131] AAC approaches may be used as part of teaching functional communication skills to non-speaking individuals as an alternative to "acting out" for the purpose of exerting independence, taking control, or informing preferences.

[133] AAC intervention in this population is directed towards the linguistic and social abilities of the child,[134] including providing the person with a concrete means of communication, as well as facilitating the development of interactional skills.

[146] Depending on their language and cognitive skills, those with aphasia may use AAC interventions such as communication and memory books, drawing, photography, written words, speech generating devices and keyboards.

[150] In some individuals, intensive practice, even long after the initial stroke, has been shown to increase the accuracy and consistency of head movements,[151] which can be used to access a communication device.

[156] Since cognition and vision are typically unaffected in ALS, writing-based systems are preferred to graphic symbols, as they allow the unlimited expression of all words in a language.

Low-tech systems, such as eye gazing or partner assisted scanning, are used in situations when electronic devices are unavailable (for example, during bathing) and in the final stages of the disease.

The individual may be taught to point to the first letter of each word they say on an alphabet board, leading to a reduced speech rate and visual cues for the listener to compensate for impaired articulation.

[163][164] Individuals with MS vary widely in their motor control capacity and the presence of intention tremor, and methods of access to AAC technology are adapted accordingly.

Visual impairments are common in MS and may necessitate approaches using auditory scanning systems, large-print text, or synthetic speech feedback that plays back words and letters as they are typed.

[19][172] The use of manual alphabets and signs was recorded in Europe from the 16th century, as was the gestural system of Hand Talk used by Native Americans to facilitate communication between different linguistic groups.

[8] The modern era of AAC began in the 1950s in Europe and North America, spurred by several societal changes; these included an increased awareness of individuals with communication and other disabilities, and a growing commitment, often backed by government legislation and funding, to develop their education, independence and rights.

[8][172] With improved technology, keyboard communication devices developed in Denmark, the Netherlands and the US increased in portability; the typed messages were displayed on a screen or strip of paper.

[8] Countries such as Sweden, Canada and the United Kingdom initiated government-funded services for those with severe communication impairments, including developing centres of clinical and research expertise.

[172] The International Society for Alternative and Augmentative Communication (ISAAC) was founded in 1983; its members included clinicians, teachers, rehabilitation engineers, researchers, and AAC users themselves.

From the 1980s, improvements in technology led to a greatly increased number, variety, and performance of commercially available communication devices, and a reduction in their size and price.

[172] AAC services became more holistic, seeking to develop a balance of aided and unaided strategies with the goal of improving functioning in the person's daily life, and greater involvement of the family.

[173] Increasingly, individuals with acquired conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, head injury, and locked-in syndrome, received AAC services.

[196] In addition, in numerous cases disabled persons have been assumed by facilitators to be typing a coherent message while the patient's eyes were closed or while they were looking away from or showing no particular interest in the letter board.

As noted by Stuart Vyse, although RPM differs from facilitated communication in some ways, "it has the same potential for unconscious prompting because the letter board is always held in the air by the assistant.

[211][212] Vyse has noted that rather than proponents of RPM subjecting the methodology to properly controlled validation research, they have responded to criticism by going on the offensive, claiming that scientific criticisms of the technique rob people with autism of their right to communicate,[209] while the authors of a 2019 review concluded that "until future trials have demonstrated safety and effectiveness, and perhaps more importantly, have first clarified the authorship question, we strongly discourage clinicians, educators, and parents of children with ASD from using RPM.