Augustan prose

Since periodicals were inexpensive to produce, quick to read, and a viable way of influencing public opinion, their numbers increased dramatically after the success of The Athenian Mercury (flourished in the 1690s but published in book form in 1709).

However, one periodical outsold and dominated all others and set out an entirely new philosophy for essay writing, and that was The Spectator, written by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele.

The highly Latinate sentence structures and dispassionate view of the world (the pose of a spectator, rather than participant) was essential for the development of the English essay, as it set out a ground wherein Addison and Steele could comment and meditate upon manners and events, rather than campaign for specific policies or persons (as had been the case with previous, more political periodical literature) and without having to rely upon pure entertainment (as in the question and answer format found in The Athenian Mercury).

However, Button's and Will's coffee shops attracted writers, and Addison and Steele became the center of their own Kit-Kat Club and exerted a powerful influence over which authors rose or fell in reputation.

Compared to the extraordinary energy that produced Richard Baxter, George Fox, Gerrard Winstanley, and William Penn, the literature of dissenting religious in the first half of the 18th century was spent.

Charles Davenant, writing as a radical Whig, was the first to propose a theoretical argument on trade and virtue with his A Discourse on Grants and Resumptions and Essays on the Balance of Power (1701).

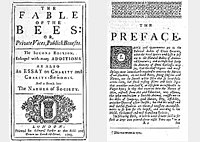

However, in 1714 he published it with its current title, The Fable of the Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits and included An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue.

Although there was a serious political and economic philosophy that derived from Mandeville's argument, it was initially written as a satire on the Duke of Marlborough's taking England to war for his personal enrichment.

These ideas had been satirized already by wits like Jonathan Swift (who insisted that readers of his A Tale of a Tub would be incapable of understanding it unless, like him, they were poor, hungry, had just had wine, and were located in a specific garret), but they were, through Smith and David Hartley, influential on the sentimental novel and even the nascent Methodist movement.

However, unlike Charles Davenant and the other radical Whig authors (including Daniel Defoe), it also did not begin with a desired outcome and work backward to deduce policy.

However, the most important single satirical source for the writing of novels came from Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605, 1615), which had been quickly translated from Spanish into other European languages including English.

It would never go out of print, and the Augustan age saw many free translations in varying styles, by journalists (Ned Ward, 1700 and Peter Motteux, 1712) as well as novelists (Tobias Smollett, 1755).

Travel writing sold very well during the period, and tales of extraordinary adventures with pirates and savages were devoured by the public, and Defoe satisfied an essentially journalistic market with his fiction.

Specifically, Fielding thought that Richardson's novel was very good, very well written, and very dangerous, for it offered serving women the illusion that they might sleep their way to wealth and an elevated title.

Women, rather than men, are the sexual aggressors, and Joseph seeks only to find his place and his true love, Fanny, and accompany his childhood friend, Parson Adams, who is travelling to London to sell a collection of sermons to a bookseller in order to feed his large family.

His own basic good nature blinds him to the wickedness of the world, and the incidents on the road (for most of the novel is a travel story) allow Fielding to satirize conditions for the clergy, rural poverty (and squires), and the viciousness of businessmen.

Instead, it is a highly tragic and affecting account of a young girl whose parents try to force her into an uncongenial marriage, thus pushing her into the arms of a scheming rake named Lovelace.

The novel is a masterpiece of psychological realism and emotional effect, and, when Richardson was drawing to a close in the serial publication, even Henry Fielding wrote to him, begging him not to kill Clarissa.

Fielding answers Richardson by featuring a similar plot device (whether a girl can choose her own mate) but by showing how family and village can complicate and expedite matches and felicity.

Laurence Sterne and Tobias Smollett held a personal dislike for one another, and their works similarly offered up oppositional views of the self in society and the method of the novel.

These two translated works show to some degree Smollett's personal preferences and models, for they are both rambling, open-ended novels with highly complex plots and comedy both witty and earthy.

They exhibit numerous voices, from the witty and learned Oxford University student, Jerry (who is annoyed to accompany his family), to the eruptive patriarch Matthew Bramble, to the nearly illiterate servant Wynn Jenkins (whose writing contains many malapropisms).

In keeping with the philosophy of Hartley (see above), the sentimental novel concentrated on characters who are quickly moved to labile swings of mood and extraordinary empathy.

A burlesque or lampoon in prose would imitate a despised author and quickly move to reductio ad absurdum by having the victim say things coarse or idiotic.

These projectors would slavishly write according to the rules of rhetoric that they had learned in school by stating the case, establishing that they have no interest in the outcome, and then offering a solution before enumerating the profits of the plan.

Gulliver then moves beyond the philosophical kingdom to the land of the Houyhnhnms, a society of horses ruled by pure reason, where humanity itself is portrayed as a group of "yahoos" covered in filth and dominated by base desires.

"Projectors" of all sorts live in the Academy of Lagado, a flying island (London) that saps all the nourishment from the land below (the countryside) and occasionally crushes, literally, troublesome cities (Dublin).

Jonathan Swift's satires obliterated hope in any specific institution or method of human improvement, but some satirists instead took a bemused pose and only made lighthearted fun.

Tom D'Urfey's Wit and Mirth: or Pills to Purge Melancholy (1719 for last authorial revision) was another satire that attempted to offer entertainment, rather than a specific bit of political action.

Martinus Scribblerus is a Don Quixote figure, a man so deeply read in Latin and Greek poetry that he insists on living his life according to that literature.