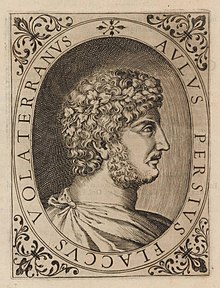

Persius

In his works, poems and satire, he shows a Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he considered to be the stylistic abuses of his poetic contemporaries.

His works, which became very popular in the Middle Ages, were published after his death by his friend and mentor, the Stoic philosopher Lucius Annaeus Cornutus.

According to the Life contained in the manuscripts, Persius was born into an equestrian family at Volterra (Volaterrae, in Latin), a small Etruscan city in the province of Pisa, of good stock on both parents' side.

He has been described as having "a gentle disposition, girlish modesty and personal beauty", and is said to have lived a life of exemplary devotion towards his mother Fulvia Sisennia, his sister and his aunt.

The manuscripts say it came from the commentary of Valerius Probus, no doubt a learned edition of Persius like those of Virgil and Horace by this same famous "grammarian" of Berytus, the poet's contemporary.

One of the points of harmony is, however, too subtle for us to believe that a forger evolved it from the works of Persius: the Life gives the impression of a "bookish" youth, who never strayed far from home and family.

[1] A keen observer of what occurs within his narrow horizon, Persius did not shy away from describing the seamy side of life (cf.

Perhaps the sensitive, homebred nature of Persius can also be glimpsed in his frequent references to ridicule, whether of great men by street gamins or of the cultured by philistines.

Persius strikes the highest note that Roman satire reached; in earnestness and moral purpose he rises far superior to the political rancour or good-natured persiflage of his predecessors and the rhetorical indignation of Juvenal.

Indeed, in some of its worst failings, straining of expression, excess of detail, exaggeration, he outbids Seneca, whilst the obscurity, which makes his little book of not seven hundred lines so difficult to read and is in no way due to great depth of thought, compares poorly with the terse clearness of the Epistolae morales.

The description of the recitator and the literary twaddlers after dinner is vividly natural, but an interesting passage which cites specimens of smooth versification and the languishing style is greatly spoiled by the difficulty of appreciating the points involved and indeed of distributing the dialogue (a not uncommon crux in Persius).

[1] The Life tells us that the Satires were not left complete; some lines were taken (presumably by Cornutus or Bassus) from the end of the work so that it might be quasi finitus.

The same authority says that Cornutus definitely blacked out an offensive allusion to the emperor's literary taste, and that we owe to him the reading of the manuscripts in Sat.

Examples of bold language or metaphor: i.25, rupto iecore exierit caprificus, 60, linguae quantum sitiat canis; iii.42, intus palleat, 81, silentia rodunt; v.92, ueteres auiae de pulmone reuello.