Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The expedition was marred by the deaths of two members during an attempt to reach Oates Land: Belgrave Edward Ninnis, who fell into a crevasse, and Xavier Mertz, who died on the harrowing return journey.

Mawson, their sledging partner, was then forced to make an arduous solo trek back to base; he missed the ship, and had to spend an extra year at Cape Denison, along with a relief party of six.

The scientific studies provided copious, detailed data – which took thirty years to completely publish – and the expedition's broad exploration program laid the groundwork for Australia's later territorial claims in Antarctica.

[7][8] Mawson's feelings of uncertainty were renewed as months of silence followed; Shackleton was still trying to float the gold mining venture and struggling to raise funds for the expedition.

[21][23] Davis supervised an extensive refit, which included alterations to her rigging and much internal reorganisation to provide appropriate accommodation, laboratories and extra storage space.

[25] The plane was shipped to Australia, where it was badly damaged during a demonstration flight, whereupon Mawson abandoned the idea of an aircraft, removing the wings and adapting the fuselage body and engine to create a motor-sledge, known as the "air-tractor".

[28][29] Before returning to Australia, Mawson recruited "the oldest resident of Antarctica",[30] the polar veteran Frank Wild, as leader of one of the proposed mainland bases.

[35] He was to be assisted by another novice dog handler, Xavier Guillaume Mertz, a Swiss ski-jumping champion and mountaineer, whose skiing expertise Mawson thought would be an important asset.

[49][n 4] On 28 July 1911, Aurora – her deck teeming with the 48 dogs that had survived the trip from Greenland,[52][n 5] laden with sledges and with more than 3,000 cases of stores on board – left London for Cardiff, where she loaded 500 tons of coal briquettes.

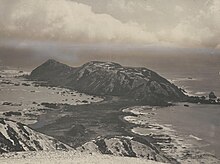

[68] On 8 January 1912, rounding a large glacier, they sailed into a gulf which Mawson later named Commonwealth Bay,[69] and on further exploration they discovered a long sheltered inlet which they dubbed Boat Harbour.

[74] The main base quarters provided a spacious living space, 7.3 by 7.3 metres (24 by 24 ft), with an attached workshop and a wide verandah for storage and housing the dogs.

[76] The party quickly discovered that their chosen location was an exceptionally windy spot; powerful katabatic winds swept down to the bay from the ice sheet, storms frequently pummelled the coast, and intense localised whirlwinds battered the men and equipment.

In rare lulls, efforts were made to erect the wireless masts and establish contact with Macquarie Island, but after repeated failures, these attempts were temporarily abandoned at the end of April.

[88] Several sledging journeys were possible in September before the weather closed in again;[89] on 9 October a particularly violent wind brought the recently erected wireless masts crashing down.

[91][92] The longest journey would be undertaken by a Far Eastern Party, consisting of Mertz, Ninnis and Mawson, which would take the dogs and attempt to reach Oates Land, some 560 kilometres (350 mi) distant in the vicinity of Cape Adare.

Mawson and Mertz retraced their steps and found a crevasse about 3.4 metres (11 ft) across; tracks on the far side made it clear that Ninnis, with his sledge and dogs, had fallen into the depths.

[97][98] Their remaining ropes were far too short of reaching even the first ledge which they measured to be at a depth of 46 metres (150 ft), so they had no option except to hope that Ninnis would answer their shouts.

Bad weather meant he could not set out again until 8 February, but during this time he managed to make a pair of homemade crampons out of the wood from packing crates and loose nails which he then used for the final leg of his journey.

When he arrived at the base, he found that the ship had indeed sailed, earlier that day, leaving a group of five – Bickerton, Bage, Madigan, Alfred Hodgeman and Archibald McLean – and a new wireless technician, Sidney Jeffryes, as a rescue party for the missing men.

This was alarming enough for the rest of the group, but when the wireless masts were re-erected early in August, Jeffryes began sending out wild messages, claiming that all the others apart from Mawson had gone insane and were trying to murder him.

[141] As the weather was improving, Mawson decided that he would take out a final sledging party with Madigan and Hodgeman, primarily to recover equipment that had been dumped or cached during the journeys of the previous year.

[150] Attempts to establish wireless contact with Cape Denison failed; they were unable to erect a suitable mast and discovered that vital parts of the transmitting equipment were missing.

[n 9] A party led by Sydney Evan Jones travelled 377 kilometres (234 mi) west to reach Gaussberg, the extinct volcano discovered by Drygalski's expedition in 1902.

[171] After the remaining members of the Cape Denison party had been picked up in December 1913, Mawson decided that, before returning home, they would conduct a coastal and seabed survey to the west, as far as the Shackleton Ice Shelf.

[175] For the next month, Mawson was engaged in a busy round of receptions and scientific meetings, before sailing for London on 1 April, accompanied by his bride, Paquita Delprat, whom he had married the previous day.

In London, he lectured to the Royal Geographical Society, visited the parents of Ninnis, and was received at Marlborough House by Alexandra, the Queen Mother, and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia.

[176] On 29 June, before his return to Australia, he was knighted at Buckingham Palace by King George V and was later the recipient of many further honours,[177] including the Royal Geographical Society's Founder's Medal in 1915.

He proposed that the Australian government should purchase Aurora and the other artefacts and equipment from the expedition for £15,000 – an amount, he reckoned, that would not only meet all outstanding debts but would finance the production of the scientific reports.

[180] Many of the expedition's personnel enlisted in the armed forces when war broke out; Bage – already an officer in the Royal Australian Engineers – was killed during the Gallipoli campaign in 1915,[181] and Leslie Blake, the cartographer and geologist of the Macquarie Island party, died after being badly wounded by a shell in France in 1918.

[140] The scientific work of the expedition covered the fields of geology, biology, meteorology, terrestrial magnetism and oceanography;[189] the vast amounts of data filled multiple reports published over a period of 30 years.