Australia–Timor-Leste spying scandal

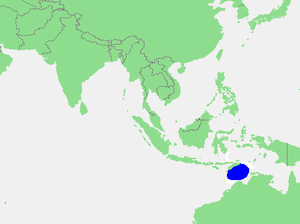

The Australia–Timor-Leste spying scandal began in 2004 when the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) clandestinely planted covert listening devices in a room adjacent to the Timor-Leste (East Timor) Prime Minister's Office at Dili, to obtain information in order to ensure Australia held the upper hand in negotiations with Timor-Leste over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap.

"[2] "Witness K", a former senior ASIS intelligence officer who led the bugging operation, confidentially noted in 2012 the Australian Government had accessed top-secret high-level discussions in Dili and exploited this during negotiations of the Timor Sea Treaty.

[4] Lead negotiator for Timor-Leste, Peter Galbraith, laid out the motives behind the espionage by ASIS: "What would be the most valuable thing for Australia to learn is what our bottom line is, what we were prepared to settle for.

The first public allegation about espionage in Timor-Leste in 2004 appeared in 2013 in an official government press release and subsequent interviews by Australian Foreign Minister Bob Carr and Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus.

However, in December 2013 the homes and office of both Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery were raided and searched by ASIO and Australian Federal Police, and many legal documents were confiscated.

[7] In June 2018 the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions filed criminal charges against Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery under the National Security Information (NSI) Act which was introduced in 2004 to deal with classified and sensitive material in court cases.

[13] In 2002, the Australian Government withdrew from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) clauses which could bind Australia to a decision of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague on matters of territorial disputes.

Over 50 members of the US Congress sent a letter to Prime Minister John Howard calling for a "fair" and "equitable" resolution of the border dispute, noting Timor-Leste's poverty.

[18] The Gillard government, in response to a letter sent by Timor-Leste's Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão requesting an explanation and a bilateral resolution to the dispute, authorised the installation of listening devices in Collaery's Canberra office.

[14] After the story became public in 2012, the Gillard government inflamed tensions with Timor-Leste by denying the alleged facts of the dispute and sending as a representative to Dili someone who was known by Gusmão to have been involved in the bugging.

[7] Attorney-General George Brandis, under lengthy questioning by a panel of Australian senators, admitted that new national security laws could enable prosecution of Witness K and his lawyer, Collaery.

[23] In September 2016, The Age newspaper in Australia published an editorial claiming Timor-Leste's attempts to resolve this matter in international courts "is an appeal to Australians' sense of fairness".

[24] On 26 September 2016, Labor Foreign Affairs spokesperson Senator Penny Wong said, "In light of this ruling [that the court can hear Timor-Leste's claims], we call on the government to now settle this dispute in fair and permanent terms; it is in both our national interests to do so".

[27] Three months after the election of the Abbott government in 2013, ASIS was authorised by Attorney-General George Brandis to raid the office of Bernard Collaery and the home of Witness K, whose passport was seized.

[30][15][31] On 4 March 2014, in response to an East Timorese request for the indication of provisional measures, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Australia not to interfere with communications between Timor-Leste and its legal advisors in the arbitral proceedings and related matters.

[34] In 2013, Timor-Leste launched a case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague to withdraw from a gas treaty that it had signed with Australia on the grounds that ASIS had bugged the East Timorese cabinet room in Dili in 2004.