Australia–China relations

Wavering between its two traditional allies, Australia chose to follow the lead of the United States, rather than Britain, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, France, Canada, and Italy (all of which switched recognition to the PRC before 1970).

As part of this political strategy, Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt explicitly recognised the continuing legitimacy of the ROC government in Taiwan in 1966, by sending an ambassador to Taipei for the first time.

[25] Although China was not specifically mentioned in the news announcements, critics interpreted it as a major blow to the Australian-Chinese relationship, by firmly allying Australia with the US in military terms in the region.

[58] In February 2018, over fears of rising Chinese influence, the Australian Government announced tougher rules on foreign buyers of agricultural land and electricity infrastructure.

[60] In April 2020, Australian Border Force intercepted faulty masks and other personal protective equipment kits that had been imported from China to help stop the spread of coronavirus.

"[113] Despite Gillard's rapprochement with the US and increased US-Australian military cooperation, Rudd's decision to leave the Quadrilateral remained an object of criticism from Tony Abbott and the Liberal Party.

[114] Gillard government's action to station US troops in Australia has been strongly criticised and viewed with suspicion by China as it asserted that the defense pact could undermine regional security.

[119] At the time, conservative commentators raised concerns that Australia may lose control over key assets, such as dairy farms, but Prime Minister Abbott gave assurances that no one would be forced into any deals.

[120] Chinese leader Xi Jinping addressed a joint-sitting of the Upper and Lower Houses of Australian Parliament in November 2014, lauding Australia's 'innovation and global influence'.

[128] In public settings, relations appeared to be warm, the main political friction coming from the farming sector, losing patience that China was slow in opening its markets.

[129] In June 2017 after a Four Corners investigation into purported Chinese attempts to influence Australian politicians and exert pressure on international students studying in Australia, Turnbull ordered a major inquiry into espionage and foreign interference laws.

[140] Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang rejected the alleged plot and said that some Australian politicians, institutions and media outlets "reached a state of hysteria and extreme nervousness".

According to Zoya Sheftalovich and Stuart Lau in September 2021: Nearly 10 years ago, Australia thought it was on the cusp of a beautiful friendship with China: It was opening up its economy to Beijing, wanted to teach Mandarin in schools and invited the Chinese president to address parliament.

These days, Australia is buying up nuclear-powered submarines to fend off Beijing, barring the country from key markets and bristling at its relentless attempts to coerce Australian politicians and media.

[142][143]The Australian ambassador to the UN was among the 22 nations that signed a letter condemning China's arbitrary detention and mistreatment of the Uyghurs and other minority groups, urging the Chinese government to close the Xinjiang internment camps, in July 2019.

[146] On 9 July 2020, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said that in response to the fear over China's new national security law, Australia has suspended the extradition treaty with Hong Kong.

In response, the Chinese Embassy in Canberra claimed that the members of the Hong Kong Legislative Council had been "elected smoothly" and criticised Australia for alleged foreign interference.

[151][152] In June 2020, China's foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying criticised Prime Minister Morrison after responding to a European Union report alleging that Beijing was disseminating disinformation about the pandemic.

[154] Western commentators, including those at The Washington Post, identified China's subsequent targeting of Australian trade, particularly beef, barley, lobsters and coal, as being "de facto economic sanctions".

[155] A spokesman for China's ministry of foreign affairs, Geng Shuang, said, "The urgent task for all countries is focusing on international cooperation rather than pointing fingers, demanding accountability and other non-constructive approaches.

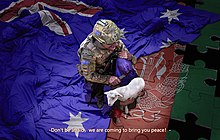

[163] On 30 November 2020, the Australian prime minister Scott Morrison demanded a formal apology from the government of China for posting an "offensive" and "outrageous" computer image of an Australian soldier holding a bloodied knife against the throat of an Afghan child, a reference to the Brereton Report in which two 14-year-old Afghanistan boys had their throats slit by Australia soldiers and covered up, which was originally created by the Chinese internet political cartoonist Wuheqilin and shared by the Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian.

[179] Although China was not specifically mentioned in the news announcements, critics interpreted it as a major blow to Australian-Chinese relationship, by firmly allying Australia with the United States in military terms in the region.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told the press that the deal would:seriously damage regional peace and stability, exacerbate an arms race and harm international nuclear nonproliferation agreements....This is utterly irresponsible conduct.

"[183] Under AUKUS, Sheftalovich and Lau say, the three allies will share advanced technologies "including artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, quantum computing, underwater systems and long-range strike capabilities."

Michael Shoebridge, a director at the influential Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) think tank, says, "It's a remarkable collapse in Australia-China relations and a massive deterioration in Australia's security outlook that's led to this outcome.

"[184] Australian opposition to the AUKUS submarine announcement has included Former Prime Minister Paul Keating's National Press Club address,[185] and in culture, Jennifer Maiden's poetry collection The China Shelf.

Marles and Wei discussed the recent Chinese interception of a Royal Australian Air Force Boeing P-8 Poseidon over the South China Sea and Oceania.

[196] At the Shangri-La Dialogue, Marles reiterated the Albanese government's desire to pursue a "productive relationship" with China while still upholding its own national interests and regional security within a rules-based system.

[211] While operating in Japan's waters in November 2023, Royal Australian Navy divers from HMAS Toowoomba were preparing to clear away fishing nets from the propellers of the ship.

[216][217] During the meeting Wong, Marles and their New Zealand counterparts Winston Peters, and Judith Collins issued a joint statement expressing concerns about human rights violations in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong.