Australian Army during World War II

[3] This expansion had little impact on improving the readiness of Australian forces upon the outbreak of the war,[4] though, as the provisions of the Defence Act 1903 restricted the pre-war Army to service in Australia and its territories including Papua and New Guinea.

While a substantial proportion of these men were granted exemptions on medical grounds or because they would suffer financial hardship if forced to enter the military, the remainder were liable for three months training followed by ongoing reserve service.

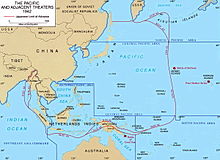

[37] After the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Act 1943 was passed Militia units were able to serve outside Australian territory in the South West Pacific Area from January 1943, though the 11th Brigade was the only major formation to do so.

Previously force structure had been heavily influenced by the British Army, and the decision to adopt an organisation to suit local conditions reflected a growing maturity and independence.

[69] In addition to the force which was sent to North Africa, two AIF brigades (the 18th and 25th) were stationed in Britain from June 1940 to January 1941 and formed part of the British mobile reserve which would have responded to any German landings.

The corps' commander, Lieutenant General Thomas Blamey, and Prime Minister Menzies both regarded the operation as risky, but agreed to Australian involvement after the British Government provided them with briefings which deliberately understated the chance of defeat.

In June the British Eighth Army made a stand just over 100 kilometres (62 mi) west of Alexandria, at the railway siding of El Alamein and the 9th Division was brought forward to reinforce this position.

[90] Meanwhile, in July 1941 the 1st Independent Company was deployed to Kavieng on New Britain in order to protect the airfield, while sections were sent to Namatanai in central New Ireland, Vila in the New Hebrides, Tulagi on Guadalcanal, Buka Passage in Bougainville, and Lorengau on Manus Island to act as observers.

While the Commonwealth forces in Johore achieved a number of local tactical victories, most notably around Gemas, Bakri, and Jemaluang,[95] they were unable to do more than slow the Japanese advance and suffered heavy casualties in doing so.

[98] The commander of the Singapore fortress, Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival, believed that the Japanese would land on the north-east coast of the island and deployed the near full-strength British 18th Division to defend this sector.

He later justified his actions saying that he had gained an understanding of how to defeat the Japanese and needed to return to Australia to pass his knowledge on, but two post-war inquiries found that he was unjustified in leaving his command.

As Japanese forces advanced through Burma towards India in early 1942, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, attempted to divert the 6th and 7th Divisions while they were en route to Australia, but Curtin refused to authorise this movement.

[106] At the start of the Pacific War the strategic port town of Rabaul in New Britain was defended by "Lark Force", which comprised the 2/22nd Battalion reinforced with coastal artillery and a poorly equipped RAAF bomber squadron.

Few members of Lark Force survived the war, as at least 130 were murdered by the Japanese on 4 February and 1,057 Australian soldiers and civilian prisoners from Rabaul were killed when the ship carrying them to Japan, the transport Montevideo Maru, was sunk by a US submarine on 1 July 1942.

The Japanese attack was successful, and resulted in the deaths of 251 civilians and military personnel, most of whom were non-Australian Allied seamen, and heavy damage to RAAF Base Darwin and the town's port facilities.

[117] Instead, in March 1942 the Japanese military adopted a strategy of isolating Australia from the United States by capturing Port Moresby in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Samoa and New Caledonia.

[117] A series of Japanese air raids against northern Australia occurred during 1942 and 1943, and while the main defence was provided by RAAF and Allied fighters, a number of Australian Army anti-aircraft batteries were also involved in dealing with this threat.

[127][128] On 26 August two AIF battalions from the 7th Division reinforced the remnants of Maroubra Force but the Japanese continued to advance along the Kokoda Track and by 16 September they reached the village of Ioribaiwa near Port Moresby.

In late 1942 and early 1943 Curtin overcame opposition within the Labor Party to extending the geographic boundaries in which conscripts could serve to include most of the South West Pacific and the necessary legislation was passed in January 1943.

[144] In the latter half of 1943 the Australian Government decided, with MacArthur's agreement, that the size of the military would be decreased to release manpower for war-related industries which were important to supplying Britain and US forces in the Pacific.

[153] While the US units had largely conducted a static defence of their positions, their Australian replacements mounted offensive operations designed to destroy the remaining Japanese forces in these areas.

The goals of this campaign were to capture Borneo's oilfields and Brunei Bay to support the US-led invasion of Japan and British-led liberation of Malaya which were planned to take place later in 1945.

[167] Although the Borneo campaign was criticised in Australia at the time, and in subsequent years, as pointless or a waste of soldiers' lives, it did achieve a number of objectives, such as increasing the isolation of significant Japanese forces occupying the main part of the NEI, capturing major oil supplies and freeing Allied prisoners of war, who were being held in deteriorating conditions.

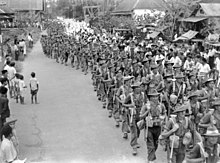

[171] Following the surrender the Australian Army faced a number of immediate operational and administrative issues, including the need to maintain security in the areas it occupied, the disarming and administration of surrendered Japanese forces in these areas, organising the return of approximately 177,000 soldiers (including prisoners of war) to Australia, the demobilisation and discharge of the bulk of the soldiers serving in the Army, and the raising of an occupation force for service in Japan.

[176] Relations between the Australian troops and Indonesians were generally good, due in part to the decision by the Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia to not load Dutch ships which were carrying military supplies bound for the NEI.

[195] Following the outbreak of war with Japan, many senior officers with distinguished records in the Middle East were recalled to Australia to lead Militia formations and fill important staff posts as the Army expanded.

Operational experience demonstrated the need for larger landing craft, so the ALCV III, an enlarged version of the ALCM II with four Ford V8 engines and twice the cargo capacity, was produced.

[229] Training for the Militia and the VDC was also hampered in the early war years by a lack of small arms, particularly after the Dunkirk evacuation when Australia dispatched its reserve stock of rifles to Britain, in an effort to help replace equipment lost by the British Army, amidst concerns of an invasion of the United Kingdom after the Fall of France.

7 Infantry Training Centre, was opened at Wilsons Promontory, Victoria, which was described as "an isolated area of high, rugged and heavily timbered mountains, precipitous valleys, swiftly running streams, and swamps."

[240] During 1943 and 1944, combined training with the RAAF and RAN was also carried out at Trinity Beach, near Cairns in preparation for amphibious operations in the South West Pacific as the Allies advanced.