Authoritarian socialism

Lipow argues that this inherently leads to authoritarianism, writing: "If the workers and the vast majority were a brutish mass, there could be no question of forming a political movement out of them nor of giving them the task of creating a socialist society.

[47] Chicago School economists such as Milton Friedman also equated socialism with centralized economic planning as well as authoritarian socialist states and command or state-directed economies, referring to capitalism as the free market.

[68] On this basis, some Marxists and non-Marxists alike, including academics, economists, and intellectuals, argue that the Soviet Union et al. were state capitalist countries and that rather than being socialist planned economies, they represented an administrative-command system.

[103] By the time of sustained growth, the Chilean government had "cooled its neo-liberal ideological fever" and "controlled its exposure to world financial markets and maintained its efficient copper company in public hands".

[108] Kristen Ghodsee, ethnographer and Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, posits that the triumphalist attitudes of Western powers at the end of the Cold War in particular the fixation with linking all socialist political ideals with the excesses of authoritarian socialism such as Stalinism had marginalized the left's response to the fusing of democracy with neoliberal ideology which helped undermine the former.

This allowed the anger and resentment that came with the ravages of neoliberalism (i.e. economic misery, hopelessness, unemployment and rising inequality throughout the former Eastern Bloc and much of the West) to be channeled into right-wing nationalist movements in the decades that followed.

Placing authoritarian socialist ideologies such as Stalinism in an international context, he argues that many forms of state interventionism used by the Stalinist government, including social cataloging, surveillance, and concentration camps, predated the Soviet regime and originated outside of Russia.

He further argues that technologies of social intervention developed in conjunction with the work of 19th-century European reformers and were greatly expanded during World War I, when state actors in all the combatant countries dramatically increased efforts to mobilize and control their populations.

[132] In Latin America, Che Guevara represented and acted on the idea that socialism was an international struggle by operating Radio Rebelde and having his station transmitted from Cuba to as far north as Washington D.C.[133] There are several elemental characteristics of the authoritarian socialist economic system that distinguish it from the capitalist market economy, namely the communist party has a concentration of power in representation of the working class and the party's decisions are so integrated into public life that its economic and non-economic decisions are part of their overall actions; state ownership of the means of production in which natural resources and capital belong to society; central economic planning, the main characteristic of an authoritarian-state socialist economy; the market is planned by a central government agency, generally a state planning commission; and socially equitable distribution of the national income in which goods and services are provided for free by the state that supplement private consumption.

This has been attributed to the Era of Stagnation, a more tolerant central government and increasing military spending caused by the nuclear arms race with the United States, especially under Ronald Reagan, whose administration pursued more aggressive relations with the Soviet Union instead of détente that was preferred in the 1970s.

[227][228][229][230][231][232] Critics also argue that neoliberal policies of liberalization, deregulation and privatisation "had catastrophic effects on former Soviet Bloc countries" and that the imposition of Washington Consensus-inspired "shock therapy" had little to do with future economic growth.

[236] For Parenti, there were clear differences between fascist and socialist regimes as the latter "made dramatic gains in literacy, industrial wages, health care and women's rights" and in general "created a life for the mass of people that was far better than the wretched existence they had endured under feudal lords, military bosses, foreign colonizers and Western capitalists".

Those regions, characterized by authoritarian traits such as uncontested party leadership, restricted civil liberties and strong unelected officials with non-democratic influence on policy, share many commonalities with the Soviet Union.

[253][254] Rather than moving in the direction of democratic capitalism followed by the majority of Eastern European countries, China and its allies, including Hungary, Nicaragua, Russia, Singapore, Turkey and Venezuela, are described as authoritarian capitalist regimes.

[257] Lenin's use of terror (instilled by a secret police apparatus) to exact social obedience, mass murder and disappearance, censoring of communications and absence of justice was only reinforced by his successor Joseph Stalin.

Conversely, the majority of Western historians have perceived him as a person who manipulated events in order to attain and then retain political power, moreover considering his ideas as attempts to ideologically justify his pragmatic policies.

[360] Through the Cultural Revolution and the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, Mao attempted to purge any subversive idea—especially capitalist or Western threat—with heavy force, justifying his actions as the necessary way for the central authority to keep power.

It builds on earlier, state-centered Asian models of development such as in South Korea and Taiwan, while taking uniquely Chinese steps designed to ensure that the Communist Party remains central to economic and political policy-making".

China developed "a hybrid form of capitalism in which it has opened its economy to some extent, but it also ensures the government controls strategic industries, picks corporate winners, determines investments by state funds, and pushes the banking sector to support national champion firms".

Dieterich argued in 1996 that both free-market industrial capitalism and 20th-century authoritarian socialism have failed to solve urgent problems of humanity like poverty, hunger, exploitation, economic oppression, sexism, racism, the destruction of natural resources and the absence of a truly participatory democracy.

[400] Leaders who have advocated for this form of socialism include Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, Néstor Kirchner of Argentina, Rafael Correa of Ecuador, Evo Morales of Bolivia and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil.

[8] In 2014, The Washington Post also argued that "Bolivia's Evo Morales, David Ortega of Nicaragua and the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez [...] used the ballot box to weaken or eliminate term limits".

Latin American countries have primarily financed their social programs with extractive exports like petroleum, natural gas and minerals, creating a dependency that some economists claim has caused inflation and slowed growth.

[431] The Bolivarian government used "centralized decision-making and a top-down approach to policy formation, the erosion of vertical power-sharing and concentration of power in the presidency, the progressive deinstitutionalization at all levels, and an increasingly paternalist relationship between state and society" in order to hasten changes in Venezuela.

[433][434] Using record-high oil revenues of the 2000s, his government nationalized key industries, created communal councils and implemented social programs known as the Bolivarian missions to expand access to food, housing, healthcare and education.

[447] By the end of Chávez's presidency in the early 2010s, economic actions performed by his government during the preceding decade such as deficit spending[448][449][450][451][452] and price controls[453][454][455][456][457] proved to be unsustainable, with the economy of Venezuela faltering while poverty,[436][444][458] inflation[454] and shortages increased.

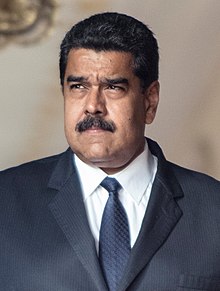

[465][non-primary source needed] In 2015, The Economist argued that the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela—now under Nicolás Maduro after Chávez's death in 2013—was devolving from authoritarianism to dictatorship as opposition politicians were jailed for plotting to undermine the government, violence was widespread and independent media shut down.

Scholars in the first camp tended to adhere to a classical liberal ideology that valued procedural democracy (competitive elections, widespread participation defined primarily in terms of voting and civil liberties) as the political means best suited to achieving human welfare.

Preceding the Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia, many socialist groups—including reformists, orthodox Marxist currents such as council communism and the Mensheviks as well as anarchists and other libertarian socialists—criticized the idea of using the state to conduct planning and nationalization of the means of production as a way to establish socialism.

According to this view, the Stalinist regimes that came into existence after 1945 were extending the bourgeois nature of prior revolutions that degenerated as all had in common a policy of expropriation and agrarian and productive development which those left communist considered negations of previous conditions and not the genuine construction of socialism.