Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

[5] Himarë had already been under Greek control since 5 November 1912, after a local Himariote, Gendarmerie Major Spyros Spyromilios, led a successful uprising that met no initial resistance.

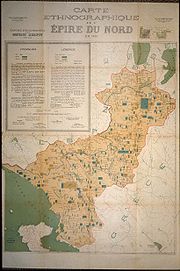

[6] By the end of the war, Greek armed forces controlled most of the historical region of Epirus, from the Ceraunian mountains along the Ionian coast to Lake Prespa in the east.

[14] Both powers were seeking to control Albania, which, in the words of Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni, would give whichever managed this "incontestable supremacy in the Adriatic".

Free of all ties, unable to live united under these conditions with Albania, Northern Epirus proclaims its independence and calls upon its citizens to undergo every sacrifice to defend the integrity of the territory and its liberties from any attack whatsoever.The flag of the new state was a variant of the Greek national flag, consisting of a white cross centred upon the blue background surmounted by the imperial Byzantine eagle in black.

Colonel Dimitrios Doulis, a local from Nivice, resigned from his post in the Greek army and joined the provisional government as minister of military affairs.

Korytsá) asking them to join the movement; however, the Greek military commander of the city, Colonel Alexandros Kontoulis, followed his official orders strictly and declared martial law, threatening to shoot any citizen raising the Northern Epirote flag.

[29] On 1 March, Kontoulis ceded the region to the newly formed Albanian gendarmerie, consisting mainly of former deserters of the Ottoman army and under the command of Dutch and Austrian officers.

[29] However, Zografos, seeing that the Great Powers would not approve the annexation of Northern Epirus to Greece, suggested three possible diplomatic solutions:[28] On 7 March, Prince William of Wied arrived in Albania, and intense fighting occurred north of Gjirokastër, in the region of Cepo, in an attempt to take control over Northern Epirus; Albanian gendarmerie units tried unsuccessfully to infiltrate southwardly, facing resistance from the Epirotes.

Albania was prepared to accept a limited Northern Epirote government, but Karapanos insisted on complete autonomy, a condition rejected by the Albanian delegates, and negotiations reached a deadlock.

On 22 March, a Sacred Band unit from Bilisht reached the outskirts of Korçë and joined the local guerillas, and fierce street fighting took place.

By the time the cease-fire order was received, the Epirote forces had secured the Morava heights near Korçë, making the city's Albanian garrison's surrender imminent.

According to its terms, the two provinces of Korçë and Gjirokastër that constituted Northern Epirus would acquire complete autonomous existence (as a corpus separatum) under the nominal Albanian sovereignty of Prince Wied.

[34] The execution of and adherence to the Protocol was entrusted to the International Control Commission, as was the organization of public administration and the departments of justice and finance in the region.

[38] The Epirote representatives, in an assembly in Delvinë, gave the final approval to the terms of the Protocol, although the delegates from Himara protested, claiming that union with Greece was the only viable solution.

[26] After the outbreak of World War I, the situation in Albania became unstable, and political chaos emerged as the country was split into a number of regional governments.

As a consequence of the anarchy in central and northern Albania, sporadic armed conflicts continued to occur in spite of the Protocol of Corfu's ratification,[40] and on 3 September Prince Wilhelm departed the country.

[41] These events worried Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, as well as the possibility that the unstable situation could spill over outside Albania, triggering a wider conflict.

During the Greek administration at the time of the First World War, it had been agreed to by Greece, Italy and the Great Powers that the final settlement of the Northern Epirote issue would be left for the post-war future.

Upon Venizelos' resignation in December, however, the succeeding royalist governments were determined to exploit the situation and predetermine the region's future by formally incorporating it into the Greek state.

This situation, according also to the development of the Balkan Front, led Italian forces in Gjirokastër to enter the area in September 1916, after gaining the approval of the Triple Entente, and to take over most of Northern Epirus.

However, the Declaration, contrary to the Protocol of Corfu, recognized minority rights only in a limited area (parts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë district and 3 villages in Himarë), without implementing any form of local autonomy.

[47] From the Albanian perspective, adopted also by Italian and Austrian sources of that time, the Northern Epirote movement was directly supported by the Greek state, with the help of a minority of inhabitants in the region, resulting in chaos and political instability in all of Albania.

However, after the region's cession to Albania, these terms were considered associated with Greek irredentist action and not granted legal status by the Albanian authorities;[51] anyone making use of them was persecuted as an enemy of the state.

[55][56] In 1991, after the collapse of the communist regime in Albania, the chairman of Greek minority organization Omonoia called for autonomy for Northern Epirus, on the basis that the rights provided for under the Albanian constitution were highly precarious.