Axial compressor

They do, however, require several rows of airfoils to achieve a large pressure rise, making them complex and expensive relative to other designs (e.g. centrifugal compressors).

The stationary airfoils, also known as vanes or stators, convert the increased kinetic energy into static pressure through diffusion and redirect the flow direction of the fluid to prepare it for the rotor blades of the next stage.

[3] The cross-sectional area between rotor drum and casing is reduced in the flow direction to maintain an optimum Mach number axial velocity as the fluid is compressed.

[citation needed] The increase in pressure produced by a single stage is limited by the relative velocity between the rotor and the fluid, and the turning and diffusion capabilities of the airfoils.

Higher stage pressure ratios are also possible if the relative velocity between fluid and rotors is supersonic, but this is achieved at the expense of efficiency and operability.

Modern jet engines use a series of compressors, running at different speeds; to supply air at around 40:1 pressure ratio for combustion with sufficient flexibility for all flight conditions.

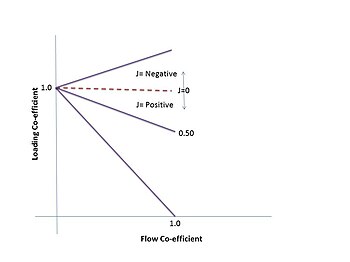

He found a non-dimensional parameter which predicted which mode of compressor instability, rotating stall or surge, would result.

The parameter used the rotor speed, Helmholtz resonator frequency of the system and an "effective length" of the compressor duct.

It had a critical value which predicted either rotating stall or surge where the slope of pressure ratio against flow changed from negative to positive.

Axial compressors, particularly near their design point are usually amenable to analytical treatment, and a good estimate of their performance can be made before they are first run on a rig.

[5] Not shown is the sub-idle performance region needed for analyzing normal ground and in-flight windmill start behaviour.

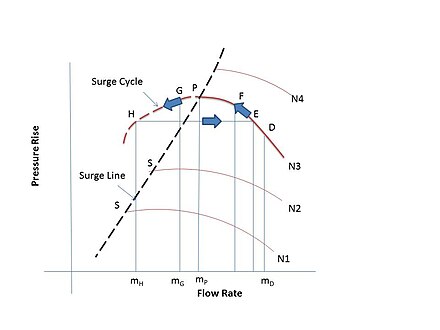

The following explanation for surging refers to running a compressor at a constant speed on a rig and gradually reducing the exit area by closing a valve.

What happens, i.e. crossing the surge line, is caused by the compressor trying to deliver air, still running at the same speed, to a higher exit pressure.

When the compressor is operating as part of a complete gas turbine engine, as opposed to on a test rig, a higher delivery pressure at a particular speed can be caused momentarily by burning too-great a step-jump in fuel which causes a momentary blockage until the compressor increases to the speed which goes with the new fuel flow and the surging stops.

That is why left portion of the curve from the surge point is called unstable region and may cause damage to the machine.

An analysis is made of rotating stall in compressors of many stages, finding conditions under which a flow distortion can occur which is steady in a traveling reference frame, even though upstream total and downstream static pressure are constant.

A. Griffith published a seminal paper in 1926, noting that the reason for the poor performance was that existing compressors used flat blades and were essentially "flying stalled".

He showed that the use of airfoils instead of the flat blades would increase efficiency to the point where a practical jet engine was a real possibility.

The only obvious effort was a test-bed compressor built by Hayne Constant, Griffith's colleague at the Royal Aircraft Establishment.

Other early jet efforts, notably those of Frank Whittle and Hans von Ohain, were based on the more robust and better understood centrifugal compressor which was widely used in superchargers.

Griffith had seen Whittle's work in 1929 and dismissed it, noting a mathematical error, and going on to claim that the frontal size of the engine would make it useless on a high-speed aircraft.

In England, Hayne Constant reached an agreement with the steam turbine company Metropolitan-Vickers (Metrovick) in 1937, starting their turboprop effort based on the Griffith design in 1938.

In the United States, both Lockheed and General Electric were awarded contracts in 1941 to develop axial-flow engines, the former a pure jet, the latter a turboprop.

As Griffith had originally noted in 1929, the large frontal size of the centrifugal compressor caused it to have higher drag than the narrower axial-flow type.

In the centrifugal-flow design the compressor itself had to be larger in diameter, which was much more difficult to fit properly into a thin and aerodynamic aircraft fuselage (although not dissimilar to the profile of radial engines already in widespread use).

On the other hand, centrifugal-flow designs remained much less complex (the major reason they "won" in the race to flying examples) and therefore have a role in places where size and streamlining are not so important.

Additionally the compressor may stall if the inlet conditions change abruptly, a common problem on early engines.

This condition, known as surging, was a major problem on early engines and often led to the turbine or compressor breaking and shedding blades.

The General Electric J79 was the first major example of a variable stator design, and today it is a common feature of most military engines.

By incorporating variable stators in the first five stages, General Electric Aircraft Engines has developed a ten-stage axial compressor capable of operating at a 23:1 design pressure ratio.