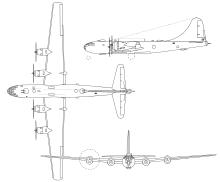

Boeing B-29 Superfortress

[2] In December 1939, the Air Corps issued a formal specification for a so-called "superbomber" that could deliver 20,000 lb (9,100 kg) of bombs to a target 2,667 mi (4,292 km) away, and at a speed of 400 mph (640 km/h).

[3] On 29 January 1940, the United States Army Air Corps issued a request to five major aircraft manufacturers to submit designs for a four-engine bomber with a range of 2,000 miles (3,200 km).

[12] The combined effects of the aircraft's highly advanced design, challenging requirements, immense pressure for production, and hurried development caused setbacks.

Unlike the unarmed first prototype,[14] the second was fitted with a Sperry defensive armament system using remote-controlled gun turrets sighted by periscopes and first flew on 30 December 1942, although the flight was terminated due to a serious engine fire.

[15] The crash killed Boeing test pilot Edmund T. Allen and his 10-man crew, 20 workers at the Frye Meat Packing Plant and a Seattle firefighter.

[17][18] This prompted an intervention by General Hap Arnold to resolve the problem, with production personnel being sent from the factories to the modification centers to speed availability of sufficient aircraft to equip the first bomb groups in what became known as the "Battle of Kansas".

[19] Although the Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radial engines later became a trustworthy workhorse in large piston-engined aircraft, early models were beset with dangerous reliability problems.

This problem was not fully cured until the aircraft was fitted with the more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-4360 "Wasp Major" in the B-29D/B-50 program, which arrived too late for World War II.

Oil flow to the valves was also increased, asbestos baffles were installed around rubber push rod fittings to prevent oil loss, thorough pre-flight inspections were made to detect unseated valves, and mechanics frequently replaced the uppermost five cylinders (every 25 hours of engine time) and the entire engines (every 75 hours).

[c] Five General Electric analog computers (one dedicated to each sight) increased the weapons' accuracy by compensating for factors such as airspeed, lead, gravity, temperature and humidity.

The affected aircraft had the same reduced defensive firepower as the nuclear weapons-delivery intended Silverplate B-29 airframes and could carry greater fuel and bomb loads as a result of the change.

[34] As a consequence of that requirement, Bell Atlanta (BA) produced a series of 311 B-29Bs that had turrets and sighting equipment omitted, except for the tail position, which was fitted with AN/APG-15 fire-control radar.

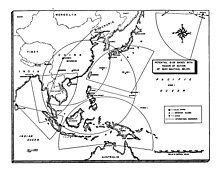

[45] The first B-29 combat losses occurred during this raid, with one B-29 destroyed on the ground by Japanese fighters after an emergency landing in China,[46] one lost to anti-aircraft fire over Yawata, and another, the Stockett's Rocket (after Capt.

Although less publicly appreciated, the mining of Japanese ports and shipping routes (Operation Starvation) carried out by B-29s from April 1945 reduced Japan's ability to support its population and move its troops.

[57][58] However, the superior range and high-altitude performance of the B-29 made it a much better choice, and after the B-29 began to be modified in November 1943 for carrying the atomic bomb, the suggestion for using the Lancaster never came up again.

Pilot Charles Sweeney credits the reversible props for saving Bockscar after making an emergency landing on Okinawa following the Nagasaki bombing.

[62] Enola Gay is fully restored and on display at the Smithsonian's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, outside Dulles Airport near Washington, D.C. Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney, dropped the second bomb, called Fat Man, on Nagasaki three days later.

In September 1945, a long-distance flight was undertaken for public relations purposes: Generals Barney M. Giles, Curtis LeMay, and Emmett O'Donnell Jr. piloted three specially modified B-29s from Chitose Air Base in Hokkaidō to Chicago Municipal Airport, continuing to Washington, D.C., the farthest nonstop distance (6,400 miles or 10,300 kilometers) to that date flown by U.S. Army Air Forces aircraft and the first-ever nonstop flight from Japan to Chicago.

[g][66] Two months later, Colonel Clarence S. Irvine commanded another modified B-29, Pacusan Dreamboat, in a world-record-breaking long-distance flight from Guam to Washington, D.C., traveling 7,916 miles (12,740 km) in 35 hours,[67] with a gross takeoff weight of 155,000 pounds (70,000 kg).

[68] Almost a year later, in October 1946, the same B-29 flew 9,422 miles (15,163 km) nonstop from Oahu, Hawaii, to Cairo, Egypt, in less than 40 hours, demonstrating the possibility of routing airlines over the polar ice cap.

The use of YB-29-BW 41-36393, the so-named Hobo Queen, one of the service test aircraft flown around several British airfields in early 1944,[70] was part of a "disinformation" program from its mention in an American-published Sternenbanner German-language propaganda leaflet from Leap Year Day in 1944, meant to be circulated within the Reich,[71] with the intent to deceive the Germans into believing that the B-29 would be deployed to Europe.

[76] On 31 July 1944, Ramp Tramp (serial number 42-6256), of the United States Army Air Forces 462nd (Very Heavy) Bomb Group was diverted to Vladivostok, Russia, after an engine failed and the propeller could not be feathered.

On 11 November 1944, during a night raid on Omura in Kyushu, Japan, the General H. H. Arnold Special (42-6365) was damaged and forced to divert to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union.

[78] The interned crews of these four B-29s were allowed to escape into American-occupied Iran in January 1945, but none of the B-29s were returned after Stalin ordered the Tupolev OKB to examine and copy the B-29 and produce a design ready for quantity production as soon as possible.

More importantly, in 1950 numbers of Soviet MiG-15 jet fighters appeared over Korea, and after the loss of 28 aircraft, future B-29 raids were restricted to night missions, largely in a supply-interdiction role.

The later B-50 Superfortress variant (initially designated B-29D) was able to handle auxiliary roles such as air-sea rescue, electronic intelligence gathering, air-to-air refueling, and weather reconnaissance.

A notable example was the eventual 65 airframes (up to 1947's end) for the Silverplate and successor-name "Saddletree" specifications built for the Manhattan Project with Curtiss Electric reversible pitch propellers.

These roles included cargo carriers (CB); rescue aircraft (SB); weather ships (WB); and trainers (TB); and aerial tankers (KB).

This included being rigged for carrying the experimental parasite fighter aircraft, such as the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin and Republic F-84 Thunderjets as in flight lock on and offs.

Superfortress 44-86292 Enola Gay (nose number 82), which dropped the first atomic bomb, was fully restored and placed on display at the Smithsonian's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air & Space Museum near Washington Dulles International Airport in 2003.