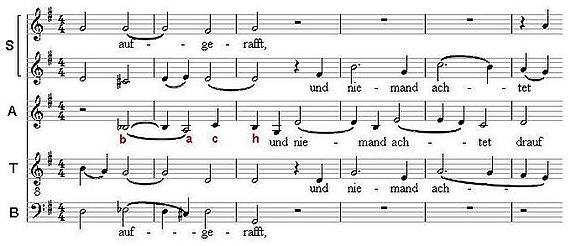

BACH motif

One of the most frequently occurring examples of a musical cryptogram, the motif has been used by countless composers, especially after the Bach Revival in the first half of the 19th century.

There the motif is mentioned thus:[1]...all those who carried the name [Bach] were as far as known committed to music, which may be explained by the fact that even the letters b a c h in this order form a melody.

[4] Later commentators wrote: "The figure occurs so often in Bach's bass lines that it cannot have been accidental.

[15] The motif's wide popularity came only after the start of the Bach Revival in the first half of the 19th century.

[4] A few mid-19th century works that feature the motif prominently are: Composers found that the motif could be easily incorporated not only into the advanced harmonic writing of the 19th century, but also into the totally chromatic idiom of the Second Viennese School; so it was used by Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and their disciples and followers.

Note that C and H are transposed down, leaving the spelling unaffected but changing the melodic contour .

The motif may be used in different ways: here it is only the beginning of an extended melody. [ 13 ]

The BACH motif from The Art of Fugue Contrapunctus XIXc is the "1st Theme'/fugue subject" of Ives' combined sonata-allegro and fugal procedures. [ 14 ]