Babylonian astronomy

This was an important contribution to astronomy and the philosophy of science, and some modern scholars have thus referred to this approach as a scientific revolution.

Classical Greek and Latin sources frequently use the term Chaldeans for the philosophers, who were considered as priest-scribes specializing in astronomical and other forms of divination.

Babylonian astronomy paved the way for modern astrology and is responsible for its spread across the Graeco-Roman empire during the 2nd Century, Hellenistic Period.

First presumed to be describing rules to a game, its use was later deciphered to be a unit converter for calculating the movement of celestial bodies and constellations.

[6] The MUL.APIN contains catalogues of stars and constellations as well as schemes for predicting heliacal risings and settings of the planets, and lengths of daylight as measured by a water clock, gnomon, shadows, and intercalations.

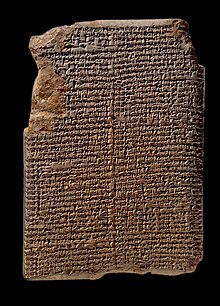

[10] The Enuma anu enlil, written during the Neo-Assyrian period in the 7th century BC,[11] comprises a list of omens and their relationships with various celestial phenomena including the motions of the planets.

[16] The Enuma Anu Enlil is a series of cuneiform tablets that gives insight on different sky omens Babylonian astronomers observed.

[18] The astrolabes (not to be mistaken for the later astronomical measurement device of the same name) are one of the earliest documented cuneiform tablets that discuss astronomy and date back to the Old Babylonian Kingdom.

[19] The thirty-six stars that make up the astrolabes are believed to be derived from the astronomical traditions from three Mesopotamian city-states, Elam, Akkad, and Amurru.

The increased use of science in astronomy is evidenced by the traditions from these three regions being arranged in accordance to the paths of the stars of Ea, Anu, and Enlil, an astronomical system contained and discussed in the MUL.APIN.

It was comprised in the general time frame of the astrolabes and Enuma Anu Enlil, evidenced by similar themes, mathematical principles, and occurrences.

A potential blend between the two that has been noted by some historians is the adoption of a crude leap year by the Babylonians after the Egyptians developed one.

He was a priest for the moon god and is credited with writing lunar and eclipse computation tables as well as other elaborate mathematical calculations.

[22] A team of scientists at the University of Tsukuba studied Assyrian cuneiform tablets, reporting unusual red skies which might be aurorae incidents, caused by geomagnetic storms between 680 and 650 BC.

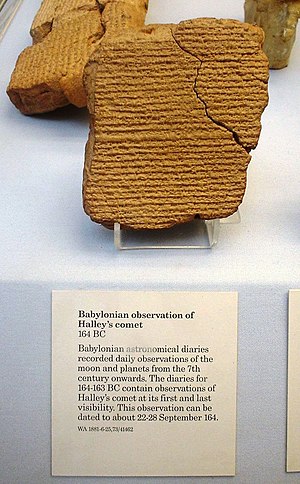

The systematic records in Babylonian astronomical diaries allowed for the observation of a repeating 18-year Saros cycle of lunar eclipses.

The Greek geographer Strabo lists Seleucus as one of the four most influential astronomers, who came from Hellenistic Seleuceia on the Tigris, alongside Kidenas (Kidinnu), Naburianos (Naburimannu), and Sudines.

[32] Seleucus, however, was unique among them in that he was the only one known to have supported the heliocentric theory of planetary motion proposed by Aristarchus,[33] where the Earth rotated around its own axis which in turn revolved around the Sun.

However, achievements in these fields by earlier ancient Near Eastern civilizations, notably those in Babylonia, were forgotten for a long time.

Since the discovery of key archaeological sites in the 19th century, many cuneiform writings on clay tablets have been found, some of them related to astronomy.

Herodotus writes that the Greeks learned such aspects of astronomy as the gnomon and the idea of the day being split into two halves of twelve from the Babylonians.

[19] Other sources point to Greek pardegms, a stone with 365-366 holes carved into it to represent the days in a year, from the Babylonians as well.

[5] In 1900, Franz Xaver Kugler demonstrated that Ptolemy had stated in his Almagest IV.2 that Hipparchus improved the values for the Moon's periods known to him from "even more ancient astronomers" by comparing eclipse observations made earlier by "the Chaldeans", and by himself.