History of the telescope

[1] Isaac Newton is credited with building the first reflector in 1668 with a design that incorporated a small flat diagonal mirror to reflect the light to an eyepiece mounted on the side of the telescope.

He had a local magistrate in Middelburg follow-up on Boreel's childhood and early adult recollections of a spectacle-maker named "Hans", who he remembered as the inventor of the telescope.

The magistrate was contacted by a then-unknown claimant– the Middelburg spectacle-maker Johannes Zachariassen, who testified that his father– Zacharias Janssen, invented the telescope and the microscope as early as 1590.

[18] Boreel's conclusion that Zacharias Janssen invented the telescope a little ahead of another spectacle maker, Hans Lippershey, was adopted by Pierre Borel in his 1656 book De vero telescopii inventore.

[24][25] Thomas described it as "by proportional Glasses duly situate in convenient angles, not only discovered things far off, read letters, numbered pieces of money with the very coin and superscription thereof, cast by some of his friends of purpose upon downs in open fields, but also seven miles off declared what hath been done at that instant in private places."

[27] The optical performance required to see the details of coins lying about in fields, or private activities seven miles away, seems to be far beyond the technology of the time,[31] and it may be that the "perspective glass" being described was a far simpler idea, originating with Bacon, of using a single lens held in front of the eye to magnify a distant view.

[32] A 1959 research paper by Simon de Guilleuma claimed that evidence he had uncovered pointed to the French born spectacle maker Juan Roget (died before 1624) as another possible builder of an early telescope that predated Hans Lippershey's patent application.

Bettini also noted the writings of Italian scholar and professor Girolamo Fracastoro in 1538, about combining lenses in eyeglasses to make the "moon or at another star" "so near that they would appear not higher than the towers".

[35] The Italian polymath Galileo Galilei was in Venice in June 1609[36] and there heard of the "Dutch perspective glass", a military spyglass,[37] by means of which distant objects appeared nearer and larger.

[38] A few days afterwards, having succeeded in making a better telescope than the first, he took it to Venice where he communicated the details of his invention to the public and presented the instrument itself to the doge Leonardo Donato, who was sitting in full council.

The name was invented by the Greek poet/theologian Giovanni Demisiani at a banquet held on April 14, 1611, by Prince Federico Cesi to make Galileo Galilei a member of the Accademia dei Lincei.

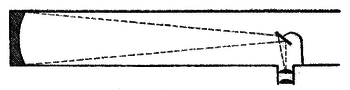

The objective was mounted on a swiveling ball-joint on top of a pole, tree, or any available tall structure and aimed by means of string or connecting rod.

Cassini discovered Saturn's third and fourth satellites in 1684 with aerial telescope objectives made by Giuseppe Campani that were 100 and 136 ft (30 and 41 m) in focal length.

[51] Niccolò Zucchi, an Italian Jesuit astronomer and physicist, wrote in his book Optica philosophia of 1652 that he tried replacing the lens of a refracting telescope with a bronze concave mirror in 1616.

No further practical advance appears to have been made in the design or construction of the reflecting telescopes for another 50 years until John Hadley (best known as the inventor of the octant) developed ways to make precision aspheric and parabolic speculum metal mirrors.

[61] After remarking that Newton's telescope had lain neglected for fifty years, they stated that Hadley had sufficiently shown that the invention did not consist in bare theory.

[62] Bradley and Samuel Molyneux, having been instructed by Hadley in his methods of polishing speculum metal, succeeded in producing large reflecting telescopes of their own, one of which had a focal length of 8 ft (2.4 m).

In 1845 William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse built his 72-inch (180 cm) Newtonian reflector called the "Leviathan of Parsonstown" with which he discovered the spiral form of galaxies.

After devoting some time to the inquiry he found that by combining two lenses formed of different kinds of glass, he could make an achromatic lens where the effects of the unequal refractions of two colors of light (red and blue) was corrected.

Adopting a hypothetical law of the dispersion of differently colored rays of light, he proved analytically the possibility of constructing an achromatic objective composed of lenses of glass and water.

[64] All of Euler's efforts to produce an actual objective of this construction were fruitless—a failure which he attributed solely to the difficulty of procuring lenses that worked precisely to the requisite curves.

[67] John Dollond agreed with the accuracy of Euler's analysis, but disputed his hypothesis on the grounds that it was purely a theoretical assumption: that the theory was opposed to the results of Newton's experiments on the refraction of light, and that it was impossible to determine a physical law from analytical reasoning alone.

[64] Dollond did not reply to this, but soon afterwards he received an abstract of a paper by the Swedish mathematician and astronomer, Samuel Klingenstierna, which led him to doubt the accuracy of the results deduced by Newton on the dispersion of refracted light.

Klingenstierna showed from purely geometrical considerations (fully appreciated by Dollond) that the results of Newton's experiments could not be brought into harmony with other universally accepted facts of refraction.

[70] In 1856–57, Karl August von Steinheil and Léon Foucault introduced a process of depositing a layer of silver on glass telescope mirrors.

The silver layer was not only much more reflective and longer lasting than the finish on speculum mirrors, it had the advantage of being able to be removed and re-deposited without changing the shape of the glass substrate.

Adaptive optics works by measuring the distortions in a wavefront and then compensating for them by rapid changes of actuators applied to a small deformable mirror or with a liquid crystal array filter.

AO was first envisioned by Horace W. Babcock in 1953, but did not come into common usage in astronomical telescopes until advances in computer and detector technology during the 1990s made it possible to calculate the compensation needed in real time.

Also, with a single star or laser the corrections are only effective over a very narrow field (tens of arcsec), and current systems operating on several 8-10m telescopes work mainly in near-infrared wavelengths for single-object observations.

Radio astronomers soon developed the mathematical methods to perform aperture synthesis Fourier imaging using much larger arrays of telescopes —often spread across more than one continent.