Attempted schisms in the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith was formed in the late 19th-century Middle East by Baháʼu'lláh, and teaches that an official line of succession of leadership is part of a divine covenant that assures unity and prevents schism.

[4][5][2] The largest extant sect is related to Mason Remey's claim to leadership in 1960, which has continued with two or three groups numbering less than 200 collectively,[6] mostly in the United States.

[14] With ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as the head of the Baháʼí community, soon Muhammad ʻAli started working against his elder brother, at first subtly and then in open opposition.

He formed the Society of Behaists, a religious denomination promoting Unitarian Bahaism in the U.S., which was later led by Shua Ullah Behai, son of Mirza Muhammad ʻAlí, after he emigrated to the United States in June 1904 at the behest of his father.

Initially, like Baháʼu'lláh,[23] he made no public statements but communicated with his brother Muhammad ʻAlí and his associates directly, or through intermediaries, in seeking reconciliation.

When it became clear that reconciliation was not possible, and fearing damage to the community, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote to the Baháʼís explaining the situation, identifying the individuals concerned and instructing the believers to sever all ties with those involved.

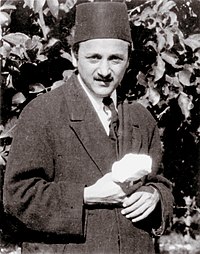

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá died, his Will and Testament explained in some detail how Muhammad ʻAlí had been unfaithful to the Covenant, identifying him as a Covenant-breaker and appointing Shoghi Effendi as leader of the Faith with the title of Guardian.

[24] The Behaists rejected the authority of the Will and Testament of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, claiming loyalty to the leadership succession as they inferred it from Baha'u'llah's Kitab-i-Ahd.

[4] In the ʻAkká area, the followers of Muhammad ʻAlí represented six families at most, they had no common religious activities,[22] and were almost wholly assimilated into Muslim society.

[25] He seized the keys of the Tomb of Baháʼu'lláh at the mansion of Bahjí, expelled its keeper, and demanded that he be recognized by the authorities as the legal custodian of that property.

However, the Palestinian authorities, after having conducted some investigations, instructed the British officer in ʻAkká to deliver the keys into the hands of the keeper loyal to Shoghi Effendi.

[26] After the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Ruth White questioned the Will's authenticity as early as 1926,[27] and openly opposed Shoghi Effendi's Guardianship, publishing several books on the subject.

Another division occurred primarily within the American Baháʼí community, which increasingly consisted of non-Persians with an interest in alternative spiritual pursuits.

When Shoghi Effendi made clear his position that the Baháʼí Faith was an independent religion with its own distinct administration through local and national spiritual assemblies, a few felt that he had overstepped the bounds of his authority.

Most prominent among them was a New York group including Mirza Ahmad Sohrab, Lewis and Julia Chanler, who founded the "New History Society", and its youth section, the Caravan of East and West.

[36] Furthermore, the Universal House of Justice had not yet been elected, which represented the only Baháʼí institution authorized to adjudicate on matters not covered by the religion's three central figures.

[38] To understand the transition following the death of Shoghi Effendi in 1957, an explanation of the roles of the Guardian, the Hands of the Cause, and the Universal House of Justice is useful.

[40][b] Among these were: In their deliberations following Shoghi Effendi's passing they determined that they were not in a position to appoint a successor, only to ratify one, so they advised the Baháʼí community that the Universal House of Justice would consider the matter after it was established.

"[46][47] The recognition as a religious court was never achieved, and the International Baháʼí Council was reformed in 1961 as an elected body in preparation for forming the Universal House of Justice.

[48] Upon the election of the Universal House of Justice at the culmination of the Ten Year Crusade in 1963, the nine Hands acting as interim head of the religion closed their office.

His followers later referred to letters and public statements of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá calling him "my son" as evidence that he had been implicitly adopted[58] but these claims were almost universally rejected by the body of the Baháʼís.

[38] In response, and after having made many prior efforts to convince Remey to withdraw his claim,[59][60] the Custodians took action and sent a cablegram to the National Spiritual Assemblies on 26 July 1960.

[49] In a 9 August 1960 letter to the other Hands, the Custodians seem to acknowledge that Remey was not senile or unbalanced, but he was carrying out a "well thought out campaign" to spread his claim.

[41] A short time later it elaborated on the situation in which the Guardian would die without being able to appoint a successor, saying that it was an obscure question not covered by Baháʼí scriptures, that no institution or individual at the time could have known the answer, and that it therefore had to be referred to the Universal House of Justice, whose election was confirmed by references in Shoghi Effendi's letters that after 1963 the Baháʼí world would be led by international plans under the direction of the Universal House of Justice.

Likewise, Remey at one point declared that the Hands of the Cause were Covenant-breakers, that they lacked any authority without a Guardian, that those following them "should not be considered Baháʼís", and that the Universal House of Justice that they helped elect in 1963 was not legitimate.

In 1966, Remey asked the Santa Fe assembly to dissolve, as well as the second International Baháʼí Council that he had appointed with Joel Marangella, residing in France, as president.

[73] The followers of Mason Remey were not organized until several of them began forming their own groups based on different understandings of succession, even before his death in 1974.

An unverified website claiming to represent Orthodox Baháʼís indicates followers in the United States and India, and a fourth Guardian named Nosrat’u’llah Bahremand.

In 1969 he was convicted of "a lewd and lascivious act" for sexually molesting a 15-year-old female patient,[87] and he served four years of a twenty-year sentence in the Montana State Prison.

Other small groups have broken away from the main body from time to time, but none of these has attracted a sizeable following.They call themselves Orthodox Bahais, and their following is small – a mere 100 members, with the largest congregation, a total of 11, living in Roswell, N.M.Rejected by his fellow Hands and the overwhelming majority of Bahá'ís, Remey was expelled from the Bahá'í Faith.