Balalaika

All have three-sided bodies; spruce, evergreen, or fir tops; and backs made of three to nine wooden sections (usually maple).

[2][4][3]: 18 Peter the Great requested balalaika performers to play at the wedding celebrations of N.M. Zotov in Saint Petersburg.

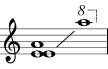

The piccolo, prima, and secunda balalaikas were originally strung with gut with the thinnest melody string made of stainless steel.

[12] An important part of balalaika technique is the use of the left thumb to fret notes on the lower string, particularly on the prima, where it is used to form chords.

Traditionally, the side of the index finger of the right hand is used to sound notes on the prima, while a plectrum is used on the larger sizes.

Because of the large size of the contrabass's strings, it is not uncommon to see players using a plectrum made from a leather shoe or boot heel.

Similarly, frets on earlier balalaikas were made of animal gut and tied to the neck so that they could be moved around by the player at will (as is the case with the modern saz, which allows for the playing distinctive to Turkish and Central Asian music).

A guard's logbook from the Moscow Kremlin records that two commoners were stopped from playing the Balalaika whilst drunk.

[18] In the 1880s, Vasily Vasilievich Andreyev, who was then a professional violinist in the music salons of St Petersburg, developed what became the standardized balalaika, with the assistance of violin maker V. Ivanov.

[19] The result of Andreyev's labours was the establishment of an orchestral folk tradition in Tsarist Russia, which later grew into a movement within the Soviet Union.

The concept of the balalaika orchestra was adopted wholeheartedly by the Soviet government as something distinctively proletarian (that is, from the working classes) and was also deemed progressive.

Significant amounts of energy and time were devoted to support and foster the formal study of the balalaika, from which highly skilled ensemble groups such as the Osipov State Russian Folk Orchestra emerged.

The movement was so powerful that even the renowned Red Army Choir, which initially used a normal symphonic orchestra, changed its instrumentation, replacing violins, violas, and violoncellos with orchestral balalaikas and domras.