Balance puzzle

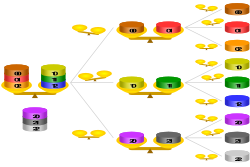

The solution to the most common puzzle variants is summarized in the following table:[1] For example, in detecting a dissimilar coin in three weighings (

weighings, one can always determine the identity and nature of a single dissimilar coin if there are

In the case of three weighings, it is possible to find and describe a single dissimilar coin among a collection of

This twelve-coin version of the problem appeared in print as early as 1945[2][3] and Guy and Nowakowski explain it "was popular on both sides of the Atlantic during WW2; it was even suggested that it be dropped over Germany in an attempt to sabotage their war effort".

[3] A well-known example has up to nine items, say coins (or balls), that are identical in weight except one, which is lighter than the others—a counterfeit (an oddball).

To find the lighter one, we can compare any two coins, leaving the third out.

It then takes only one more move to identify the light coin from within that lighter stack.

So in two weighings, we can find a single light coin from a set of 3 × 3 = 9.

One is easily scalable to a higher number of coins by using base-three numbering: labelling each coin with a different number of three digits in base three, and positioning at the n-th weighing all the coins that are labelled with the n-th digit identical to the label of the plate (with three plates, one on each side of the scale labelled 0 and 2, and one off the scale labelled 1).

It is less straightforward for this problem, and the second and third weighings depend on what has happened previously, although that need not be the case (see below).

Picking out the one counterfeit coin corresponding to each of the 27 outcomes is always possible (13 coins one either too heavy or too light is 26 possibilities) except when all weighings are balanced, in which case there is no counterfeit coin (or its weight is correct).

If coins 0 and 13 are deleted from these weighings they give one generic solution to the 12-coin problem.

In a relaxed variation of this puzzle, one only needs to find the counterfeit coin without necessarily being able to tell its weight relative to the others.

It is not possible to do any better, since any coin that is put on the scales at some point and picked as the counterfeit coin can then always be assigned weight relative to the others.

A method which weighs the same sets of coins regardless of outcomes lets one either The three possible outcomes of each weighing can be denoted by "\" for the left side being lighter, "/" for the right side being lighter, and "–" for both sides having the same weight.

Except for "–––", the sets are divided such that each set on the right has a "/" where the set on the left has a "\", and vice versa: As each weighing gives a meaningful result only when the number of coins on the left side is equal to the number on the right side, we disregard the first row, so that each column has the same number of "\" and "/" symbols (four of each).

The rows are labelled, the order of the coins being irrelevant: Using the pattern of outcomes above, the composition of coins for each weighing can be determined; for example the set "\/– D light" implies that coin D must be on the left side in the first weighing (to cause that side to be lighter), on the right side in the second, and unused in the third: The outcomes are then read off the table.

For example, if the right side is lighter in the first two weighings and both sides weigh the same in the third, the corresponding code "//– G heavy" implies that coin G is the odd one, and it is heavier than the others.

[5] In another generalization of this problem, we have two balance scales that can be used in parallel.

th object is greater (smaller) by a constant (unknown) value if

The incompleteness of initial information about the distribution of weights of a group of objects is characterized by the set of admissible distributions of weights of objects

which is also called the set of admissible situations, the elements of

an algorithm of identification the types identifies also the situations in

As an example the perfect dynamic (two-cascade) algorithms with parameters

At the same time, it is established that a static WA (i.e. weighting code) with the same parameters does not exist.

In this case the uncertainty domain (the set of admissible situations) contains

situations, i.e. the constructed WA lies on the Hamming bound for

To date it is not known whether there are other perfect WA that identify the situations in

(corresponding to the Hamming bound for ternary codes) which is, obviously, necessary for the existence of a perfect WA.

which determines the parameters of the constructed perfect WA.