Russians in the Baltic states

Most of the present-day Baltic Russians are migrants from forcible population transfers in the Soviet occupation era (1944-1991) and their descendants[1], though a relatively small fraction of them can trace their ancestry in the area back to previous centuries.

Communist party members who had arrived in the area with the initial annexation in 1940 and the puppet regimes established evacuated to other parts of the Soviet Union; those who fell into German hands were treated harshly or murdered.

[4] Immediately after the war, a major influx from other USSR republics primarily of ethnic Russians took place in the Baltic states as part of a de facto process of Russification.

[3] However, the flow of immigrants did not stop entirely in Lithuania, and there were further waves of Russian workers who came to work on major construction projects, such as power plants.

This continuity of the Baltic states with their first period of independence has been used to re-adopt pre-World War II laws, constitutions, and treaties and to formulate new policies, including in the areas of citizenship and language.

Those that failed to request Russian citizenship during the time window it was offered were granted permanent residency "non-citizen" status.

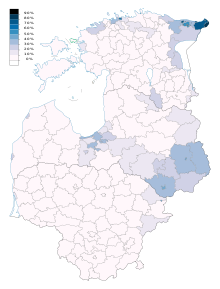

In all three countries, the rural settlements are inhabited almost entirely by the main national ethnic groups, except some areas in eastern Estonia and Latvia with a longer history of Russian and mixed villages.

Thousands of Russians from Riga, Tallinn and Vilnius, holding EU passports, now live in London, Dublin and other cities in the UK and Ireland.

However, the purported difficulty of the initial language tests became a point of international contention, as the government of Russia, the Council of Europe, and several human rights organizations claiming that they made it impossible for many older Russians who grew up in the Baltic region to gain citizenship.

As a result, the tests were altered,[20][citation needed] but a large percentage of Russians in Latvia and Estonia still have non-citizen or alien status.

Some representatives of the ethnic Russian communities in Latvia and Estonia have claimed discrimination by the authorities, these calls frequently being supported by Russia.

[24] In recent years, as the Russian political leaders have begun to speak about the "former Soviet space" as their sphere of influence,[25] such claims are a source of annoyance, if not alarm, in the Baltic countries.

[24][26] Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have since 2004 become members of NATO and the European Union (EU) to provide a counterbalance to Russia's claims to speak for the interests of ethnic Russian residents of these countries.

[citation needed] There are a number of political parties and politicians in the Baltic states who claim to represent the Russian-speaking minority.

These forces are particularly strong in Latvia represented by the Latvian Russian Union which has one seat in the European Parliament held by Tatjana Ždanoka and the more moderate Harmony party which is currently the largest faction in the Saeima with 24 out of 100 deputies, the party of the former Mayor of Riga Nils Ušakovs and with one representative in the European Parliament currently Andrejs Mamikins.

In 2011 pro-Russian groups in Latvia collected sufficient signatures to initiate the process of amending the Constitution to give Russian the status of an official language.