Bandura

The use of the term bandore (or bandora) stems from a now discredited assumption, initially made by Russian musicologist A. Famintsyn, that the word was borrowed directly from England.

In that year, Byzantine Greek chronicles mention Bulgar warriors who travelled with lute-like instruments they called kitharas.

The invention of an instrument combining organological elements of lute and psaltery is sometimes credited to Francesco Landini, an Italian lutenist-composer during the trecento.

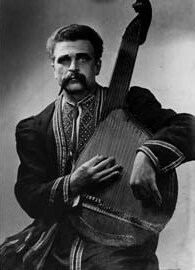

In the Hetman state in left-bank Ukraine, the bandura underwent significant transformations with the development of a professional class of itinerant blind musicians called kobzars.

Empress Elisabeth of Russia (the daughter of Peter the Great) had a long-standing relationship and maybe a morganatic marriage with her Ukrainian court bandurist, Olexii Rozumovsky.

[7] In 1908, the Mykola Lysenko Institute of Music and Drama in Kyiv began offering classes in bandura playing, instructed by kobzar Ivan Kuchuhura Kucherenko.

In the major Russian speaking cities, they were often treated like common street beggars by the non-Ukrainian population, being arrested and having their instruments destroyed.

This was because of the association of the bandura with specific aspects of Ukrainian history, and also the prevalence of religious elements in the kobzar repertoire that eventually was adopted by the latter-day bandurists.

A significant section of the repertoire consisted of para-liturgical chants (kanty) and psalms sung by the kobzari outside of churches as the latter were often suspicious of, and sometimes hostile to, the kobzars' moral authority.

Because of these restrictions and the rapid disappearance of kobzars and bandurists, the topic of the minstrel art of the itinerant blind bandura players was again brought up for discussion at the XIIth Archeological Conference held in Kharkiv in 1902.

After the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich, the instrument continued to be played by wandering, blind musicians known as kobzari in Right-bank Ukraine.

With the growing appreciation of bandurist capellas as an art form came the accelerated development of technology related to the performance on the bandura.

By 1928, restrictions came into force that directly affected the lifestyle of the traditional kobzars, and stopped them from traveling without a passport and performing without a license.

In this period, documents attest to the fact that a large number of non-blind bandurists were also arrested at this time, however they received relatively light sentences of 2–5 years in penal colonies or exile.

When these sanctions proved to have little effect on the growth in interest in such cultural artifacts, the carriers of these artefacts, such as bandurists, often came under harsh persecution from the Soviet authorities.

At the height of the Great Purge in the late 1930s, the official State Bandurist Capella in Kyiv was changing artistic directors every 2 weeks because of these political arrests.

In recent years evidence of this has emerged, pointing to an event (often masked as an ethnographic conference) that was held in Kharkiv, the capital of the Ukrainian SSR, in December 1933 – January 1934.

Many itinerant street musicians from all over the country, specifically blind kobzars and lirnyks, were invited to attend, amounting to an estimated 300 participants.

In 1978, evidence came to light (Solomon Volkov's Testimony: The Memoirs of Shostakovych and Leonid Plyushch's History's Carnival) (1978) about the mass murder of the Ukrainian blind musicians by the Soviet authorities.

The location of this atrocity has recently been discovered on the territory of recreation building owned by the KGB (or the NKVD) in the area of Piatykhatky, Kharkiv Oblast.

After World War II, and particularly after the death of Joseph Stalin, these restrictions were somewhat relaxed and bandura courses were again re-established in music schools and conservatories in Ukraine, initially at the Kyiv conservatory under the direction of Khotkevych's student Volodymyr Kabachok, who had returned to Kyiv after being released from a gulag labour camp in Kolyma.

Conservatory courses were re-established and, in time, the serial manufacture of banduras was rekindled by musical instrument factories in Chernihiv and Lviv.

In Germany in 1948, the Honcharenko brothers in the workshops of the Ukrainian Bandurist Chorus continued to refine the mechanism to make it more reliable for the concert stage and also even out the tone of the instrument.

Although direct and open confrontation ceased, the Communist party continued to control and manipulate the art of the bandurist through a variety of indirect means.

(e.g. Serhiy Bashtan was the first secretary of the Communist Party at the Kyiv conservatory for over 30 years and, in that position, restricted the development of many aspects of Ukrainian culture in the premier music establishment in Ukraine).

In the 1960s the foundation of the modern professional bandura technique and repertoire were laid by Bashtan based on work he had done with students from the Kyiv Conservatory.

Significant contributions to modern bandura construction were made by Khotkevych, Leonid Haydamaka, Peter Honcharenko, Skliar, Herasymenko and William Vetzal.

Several notable, present-day makers of the instrument include the late Budnyk, Tovkailo, Rusalim Kozlenko, Vasyl Boyanivsky, Fedynskyj, and Bill Vetzal.

A category for authentic bandura playing has been included in the Hnat Khotkevych International Folk Instruments competition held in Kharkiv every 3 years.

Another line of Kyiv-style banduras was developed by Vasyl Herasymenko and continues to be made by the Trembita Musical Instrument Factory in Lviv.