Bank War

favored merchants and speculators at the expense of farmers and artisans, appropriated public money for risky private investments and interference in politics, and conferred economic privileges on a small group of stockholders and financial elites, thereby violating the principle of equal opportunity.

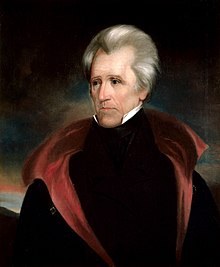

His veto message was a polemical declaration of the social philosophy of the Jacksonian movement that pitted "the planters, the farmers, the mechanic and the laborer" against the "monied interest", benefiting the wealthy at the expense of the common people.

A reaction set in throughout America's financial and business centers against Biddle's maneuvers, compelling the Bank to reverse its tight money policies, but its chances of being rechartered were all but finished.

[11] In 1815, Secretary of State James Monroe told President Madison that a national bank "would attach the commercial part of the community in a much greater degree to the Government [and] interest them in its operations…This is the great desideratum [essential objective] of our system.

"[12] Support for this "national system of money and finance" grew with the post-war economy and land boom, uniting the interests of eastern financiers with southern and western Republican nationalists.

[26] Andrew Jackson, previously a major general in the United States Army and former territorial governor of Florida, sympathized with these concerns, privately blaming the Bank for causing the Panic by contracting credit.

However, he was also Speaker of the House, and he maneuvered the election in favor of Adams, who in turn made Clay Secretary of State, an office that in the past had served as a stepping stone to the presidency.

Inflation caused during the Revolutionary War by printing enormous amounts of paper money added to the distrust, and opposition to it was a major reason for Hamilton's difficulties in securing the charter of the First Bank of the United States.

This would lead to lenders demanding that the banks take back their devalued paper in exchange for specie, as well as debtors trying to pay off loans with the same deflated currency, seriously disrupting the economy.

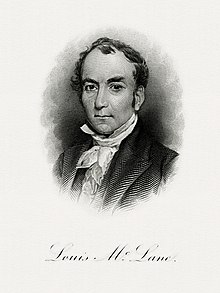

[74] In January 1829, John McLean wrote to Biddle urging him to avoid the appearance of political bias in light of allegations of the Bank interfering on behalf of Adams in Kentucky.

Biddle responded that the "great hazard of any system of equal division of parties at a board is that it almost inevitably forces upon you incompetent or inferior persons in order to adjust the numerical balance of directors".

[88] Jackson's criticisms were shared by "anti-bank, hard money agrarians"[89] as well as eastern financial interests, especially in New York City, who resented the national bank's restrictions on easy credit.

[99] Lewis and other administration insiders continued to have encouraging exchanges with Biddle, but in private correspondence with close associates, Jackson repeatedly referred to the institution as being "a hydra of corruption" and "dangerous to our liberties".

"[140] Most historians have argued that Biddle reluctantly supported recharter in early 1832 due to political pressure from Clay and Webster,[139][140][143] though the Bank president was also considering other factors.

In addition, Biddle had to consider the wishes of the Bank's major stockholders, who wanted to avoid the uncertainty of waging a recharter fight closer to the expiration of the charter.

Most notably, these were Thomas Hart Benton in the Senate and future president James K. Polk, member of the House of Representatives from Tennessee, as well as Blair, Treasury Auditor Kendall, and Attorney General Roger Taney in his cabinets.

[167] The executive branch, Jackson averred, when acting in the interests of the American people,[168] was not bound to defer to the decisions of the Supreme Court, nor to comply with legislation passed by Congress.

[173] Jackson gave no credit to the Bank for stabilizing the country's finances[166] and provided no concrete proposals for a single alternate institution that would regulate currency and prevent over-speculation—the primary purposes of the B.U.S.

[178] He pitted the idealized "plain republican" and the "real people"—virtuous, industrious and free[179][180]—against a powerful financial institution—the "monster" Bank,[181] whose wealth was purportedly derived from privileges bestowed by corrupt political and business elites.

In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society-the farmers, mechanics, and laborers-who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.

Jackson, however, routinely used the veto to allow the executive branch to interfere in the legislative process, an idea Clay thought "hardly reconcilable with the genius of representative government".

[201] He also had tens of thousands of Jackson's veto messages circulated throughout the country, believing that those who read it would concur in his assessment that it was in essence "a manifesto of anarchy" addressed directly to a "mob".

[221][225] Vice President Martin Van Buren tacitly approved the maneuver, but declined to publicly identify himself with the operation, for fear of compromising his anticipated presidential run in 1836.

"[266] Jackson and Secretary Taney both exhorted Congress to uphold the removals, pointing to Biddle's deliberate contraction of credit as evidence that the central bank was unfit to store the nation's public deposits.

[269] The national economy following the withdrawal of the remaining funds from the Bank was booming and the federal government through duty revenues and sale of public lands was able to pay all bills.

The origins of this crisis can be traced to the formation of an economic bubble in the mid-1830s that grew out of fiscal and monetary policies passed during Jackson's second term, combined with developments in international trade that concentrated large quantities of gold and silver in the United States.

[306] Among these policies and developments were the passage of the Coinage Act of 1834, actions pursued by Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, and a financial partnership between Biddle and Baring Brothers, a major British merchant banking house.

[310] State-chartered financial institutions, unshackled from the regulatory oversight previously provided by the B.U.S., started engaging in riskier lending practices that fueled a rapid economic expansion in land sales, internal improvement projects, cotton cultivation, and slavery.

Soon afterward, Jackson signed the Specie Circular, an executive order mandating that sales of public lands in parcels over 320 acres be paid for only in gold and silver coin.

[334] Daniel Walker Howe criticizes Jackson's hard money policies and claims that his war on the Bank "brought little if any benefit" to the common men who made up the majority of his supporters.