Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th U.S. secretary of state under presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore.

Webster is widely regarded as an important and talented attorney, orator, and politician, but historians and observers have offered mixed opinions on his moral qualities and ability as a national leader.

[13] In order to help support his brother Ezekiel's study at Dartmouth, Webster temporarily resigned from the law office to work as a schoolteacher at Fryeburg Academy in Maine.

[25] The Rockingham Memorial, which was largely written by Webster, challenged Madison's reasons for going to war, arguing that France had been just as culpable in impeding American trade as Britain had and raising the specter of secession.

While Speaker of the House Henry Clay and Congressman John C. Calhoun worked to pass Madison's proposals, other Democratic-Republicans opposed these policies because they conflicted with the party's traditional commitment to a weaker federal government.

[37] He had been highly regarded in New Hampshire since his days in Boscawen and was respected for his service in the House of Representatives, but he came to national prominence as counsel in a number of important Supreme Court cases.

[39] He also represented numerous clients outside of Supreme Court cases, including prominent individuals such as George Crowninshield, Francis Cabot Lowell, and John Jacob Astor.

[45] He remained politically active during his time out of Congress, serving as a presidential elector, meeting with officials like Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, and delivering a well-received speech that attacked high tariffs.

[62] In 1825, President Adams set off a partisan realignment by putting forward an ambitious domestic program, based on Clay's American System, that included a vast network of federally-funded infrastructure projects.

States' rights Democratic-Republicans, including Senator Martin Van Buren and Vice President John C. Calhoun, strongly opposed the program and rallied around Jackson.

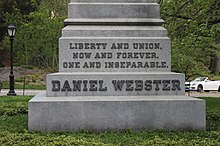

[69] When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood!

Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic... not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured, bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as "What is all this worth?"

[70] The Jackson administration suffered from factionalism between supporters of Secretary of State Van Buren and Vice President Calhoun, the latter of whom took a prominent role in propounding the doctrine of nullification.

[80] Instead, he undertook a subtle campaign to win the National Republican nomination, planning a tour of the Northeast and the Northwest; His angling for the presidency marked the start of an ambivalent relationship between Clay and Webster.

He helped ensure that Congress approved a renewal of the charter without making any major modifications, such as a provision that would allow states to prevent the national bank from establishing branches within their borders.

Webster strongly approved of the Proclamation, telling an audience at Faneuil Hall that Jackson had articulated "the true principles of the Constitution," and that he would give the president "my entire and cordial support" in the crisis.

At the same time, he opposed Clay's efforts to end the crisis by lowering tariff rates, as he believed that making concessions to Calhoun's forces would set a bad precedent.

[99] With Clay showing no indication of making another run, Webster hoped to become the main Whig candidate in the 1836 election, but General William Henry Harrison and Senator Hugh Lawson White retained strong support in the West and the South, respectively.

[101] Webster's chances also suffered from his lingering association with the Federalist Party, his close relationship with elite politicians and businessmen, and his lack of appeal among the broad populace; Robert Remini writes that the American public "admired and revered him but did not love or trust him.

[109] His debt was exacerbated by his propensity for lavishly furnishing his estate and giving away money with "reckless generosity and heedless profusion," in addition to indulging the smaller-scale "passions and appetites" of gambling and alcohol.

"[112] Webster attacked Van Buren's proposals to address the economic crisis, including the establishment of an Independent Treasury system,[113] and he helped arrange for the rescinding of the Specie Circular.

[123] The administration put a new emphasis on American influence in the Pacific Ocean, reaching the first U.S. treaty with China, seeking to partition Oregon Country with Britain, and announcing that the United States would oppose any attempt to colonize the Hawaiian Islands.

[162] Due to a prosperous economy and various other trends, few Whigs pushed for a revival of the national bank and other long-standing party policies during the Fillmore administration, and the Compromise of 1850 became the central political issue.

[167] When the New York & Erie Rail Road was completed in May 1851, President Fillmore and several members of his cabinet, including Webster, made a special, two-day excursion run to open the railway.

[177] An expedition to Cuba led by Narciso López precipitated a diplomatic crisis with Spain, but Fillmore, Webster, and the Spanish government worked out a series of face-saving measures that prevented an outbreak of hostilities from occurring.

[180] Another candidate emerged in the form of General Winfield Scott, who, like previously successful Whig presidential nominees William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, had earned fame for his martial accomplishments.

[193] After the death of his first wife, Webster was frequently the subject of rumors in Washington regarding his alleged promiscuity; many suspected that the painter Sarah Goodridge, with whom he had a close relationship, was his mistress.

[196] Webster's older son, Fletcher, married a niece of Joseph Story, established a profitable law practice, served as chief clerk of the State Department, and was the only one of his siblings to outlive his father.

Peaceable secession is an utter impossibility .... We could not separate the states by any such line if we were to draw it .... Remini writes that "whether men hated or admired [Webster], all agreed ... on the majesty of his oratory, the immensity of his intellectual powers, and the primacy of his constitutional knowledge.

[213] Bartlett, however, emphasizing Webster's private life, says his great oratorical achievements were in part undercut by his improvidence with money, his excessively opulent lifestyle, and his numerous conflict-of-interest situations.