Sharecropping

In exchange for the land and supplies, the cropper would pay the owner a share of the crop at the end of the season, typically one-half to two-thirds.

Decentralized sharecropping involves virtually no role for the landlord: plots are scattered, peasants manage their own labor and the landowners do not manufacture the crops.

[11] Economic historian Pius S. Nyambara argued that Eurocentric historiographical devices such as "feudalism" or "slavery" often qualified by weak prefixes like "semi-" or "quasi-" are not helpful in understanding the antecedents and functions of sharecropping in Africa.

15, which announced that he would temporarily grant newly freed families 40 acres of this seized land on the islands and coastal regions of Georgia.

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson, as one of the first acts of Reconstruction, instead ordered all land under federal control be returned to the owners from whom it had been seized.

[16] Not with standing, many formerly enslaved people, now called freedmen, having no land or other assets of their own, needed to work to support their families.

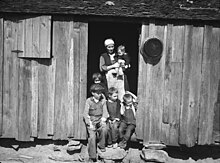

Initially, sharecroppers in the American South were almost all formerly enslaved black people, but eventually cash-strapped indigent white farmers were integrated into the system.

[21] In addition to this, landowners, threatening to not renew the lease at the end of the growing season, were able to apply pressure to their tenants.

Around this time, sharecroppers began to form unions protesting against poor treatment, beginning in Tallapoosa County, Alabama in 1931 and Arkansas in 1934.

Membership in the Southern Tenant Farmers Union included both blacks and poor whites, who used meetings, protests, and labor strikes to push for better treatment.

[27] Landless farmers who fought the sharecropping system were socially denounced, harassed by legal and illegal means, and physically attacked by officials, landlords' agents, or in extreme cases, angry mobs.

[30]The sharecropping system in the U.S. increased during the Great Depression with the creation of tenant farmers following the failure of many small farms throughout the Dustbowl.

[13][31] As a result, many sharecroppers were forced off the farms, and migrated to cities to work in factories, or became migrant workers in the Western United States during World War II.

John Heath and Hans P. Binswanger write that "evidence from around the world suggests that sharecropping is often a way for differently endowed enterprises to pool resources to mutual benefit, overcoming credit restraints and helping to manage risk.

"[37] Sharecropping agreements can be made fairly, as a form of tenant farming or sharefarming that has a variable rental payment, paid in arrears.

[38] According to sociologist Edward Royce, "adherents of the neoclassical approach" argued that sharecropping incentivized laborers by giving them a vested interest in the crop.

[21] Sharecropping may allow women to have access to arable land, albeit not as owners, in places where ownership rights are vested only in men.

[39] The theory of share tenancy was long dominated by Alfred Marshall's famous footnote in Book VI, Chapter X.14 of Principles[40] where he illustrated the inefficiency of agricultural share-contracting.

[42] He also showed that in the presence of transaction costs, share-contracting may be preferred to either wage contracts or rent contracts—due to the mitigation of labor shirking and the provision of risk sharing.

It has also been argued that the sharecropping institution can be explained by factors such as informational asymmetry (Hallagan, 1978;[49] Allen, 1982;[50] Muthoo, 1998),[51] moral hazard (Reid, 1976;[52] Eswaran and Kotwal, 1985;[53] Ghatak and Pandey, 2000),[54] intertemporal discounting (Roy and Serfes, 2001),[55] price fluctuations (Sen, 2011)[56] or limited liability (Shetty, 1988;[57] Basu, 1992;[58] Sengupta, 1997;[59] Ray and Singh, 2001).