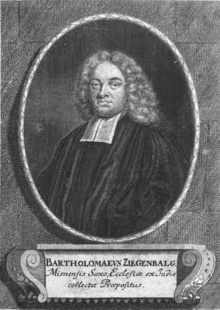

Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg

Through his father he was related to the sculptor Ernst Friedrich August Rietschel, and through his mother's side to the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte.

Under the patronage of King Frederick IV of Denmark, Ziegenbalg, along with his fellow student, Heinrich Plütschau, became the first Protestant missionaries to India.

Frederick IV of Denmark, under the influence of August Hermann Francke (1663–1727), a professor of divinity in the University of Halle (in Saxony), proposed that one of the professor's eminently skilled and religiously enthusiastic pupils, Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, be appointed to kindle in "the heathen at Tranquebar"[citation needed] the desired holy spark.

"Though the piety and zeal of Protestants had often excited an anxious desire to propagate the pure and reformed faith of the gospel in heathen countries, the establishment and defence against the Polish adversaries at home, together with the want of suitable opportunities and facilities for so great a work, combined during the first century after the Reformation, to prevent them from making any direct or vigorous efforts for this purpose.

Ove Gjedde who, in 1618, had commandeered the expedition to Lanka, initiated a treaty with the king of Tanjore to rent an area no more than "five miles by three in extent", resulting in the setting up of a fort, which still stands, though the Danes relinquished control of Tranquebar in 1845 to the British.

After initial conflict with the East India Company, which even led to a four-month incarceration of Ziegenbalg,[7] the two established the Danish-Halle Mission.

Stephen Neill notes this curious serendipity: Ziegenbalg possibly spent more time picking up the local tongue than in preaching incomprehensibly and in vain to a people who would then have thought him quite remarkable.

This reaction by native Indians was unusual and Ziegenbalg's work did not generally encounter unfriendly crowds; his lectures and classes drawing considerable interest from locals.

This incident arose from Ziegenbalg's intervention on behalf of the widow of a Tamil barber over a debt between her late husband and a Catholic who was employed by the company as a translator.

After all this time spent in blood-wrenching and sweat-drenching scholarship, Ziegenbalg wrote numerous texts in Tamil, for dissemination among Hindus.

He commenced his undertaking of translating the New Testament in 1708 and completed it in 1711, though printing was delayed till 1714, because of Ziegenbalg's insistent, perfectionist revisions.

But from the start, Ziegenbalg’s work was exposed to criticism on a variety of grounds" and that Johann Fabricius’ update on the pioneering text was so clearly superior, "before long the older version ceased to be used."

[13] In a letter dated 7/4/1713 to George Lewis, the Anglican chaplain at Madras, and first printed in Portuguese, on the press the mission had recently received from the Society, for Promoting Christian Knowledge, Ziegenbalg writes: "We may remember on this Occasion, how much the Art of Printing contributed to the Manifestation of divine Truths, and the spreading of Books for that End, at the Time of the happy Reformation, which we read of in History, with Thanksgiving to Almighty God.

"[14] Following this, he began translating the Old Testament, building "himself a little house in a quiet area away from the centre of the town, where he could pursue tranquilly what he regarded as the most important work of all.

However, when he sent these volumes to Halle for publication, his mentor wrote that the duty of the missionaries was "to extirpate heathenism, and not to spread heathenish nonsense in Europe".

[16] S. Muthiah in his fond remembrance ("The Legacy that Ziegenbalg left[usurped]") ends with an inventory of the man's lesser-known works: "Apart from the numerous Tamil translations of Christian publications he made, he wrote several books and booklets that could be described as being Indological in nature.

"The four qualities which Fabricius found in the originals were lucidity, strength, brevity and appropriateness; these were sadly lacking in the existing Tamil translation, but he hoped that by the help of God he had been able to restore them.

Stephen Neill summarises Ziegenbalg's failures and the cause of tragedy in his life, thus: "He was little too pleased with his position as a royal missionary, and too readily inclined to call on the help of the civil power in Denmark.