San people

[a][4] Their recent ancestral territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho,[5] and South Africa.

"San" comes from a derogatory Khoekhoe word used to refer to foragers without cattle or other wealth, from a root saa "picking up from the ground" + plural -n in the Haiǁom dialect.

[15] The San refer to themselves as their individual nations, such as ǃKung (also spelled ǃXuun, including the Juǀʼhoansi), ǀXam, Nǁnǂe (part of the ǂKhomani), Kxoe (Khwe and ǁAni), Haiǁom, Ncoakhoe, Tshuwau, Gǁana and Gǀui (ǀGwi), etc.

[24] These meetings included the Common Access to Development Conference organized by the Government of Botswana held in Gaborone in 1993,[18] the 1996 inaugural Annual General Meeting of the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) held in Namibia,[25] and a 1997 conference in Cape Town on "Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage" organized by the University of the Western Cape.

[35] The Bantu term Batwa refers to any foraging tribesmen and as such overlaps with the terminology used for the "Pygmoid" Southern Twa of South-Central Africa.

San were traditionally semi-nomadic, moving seasonally within certain defined areas based on the availability of resources such as water, game animals, and edible plants.

[37] Peoples related to or similar to the San occupied the southern shores throughout the eastern shrubland and may have formed a Sangoan continuum from the Red Sea to the Cape of Good Hope.

The age rule resolves any confusion arising from kinship terms, as the older of two people always decides what to call the younger.

Women gather fruit, berries, tubers, bush onions, and other plant materials for the band's consumption.

[51] Depending on location, the San consume 18 to 104 species, including grasshoppers, beetles, caterpillars, moths, butterflies, and termites.

The most divergent (earliest branching) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African San groups.

[66][67] A 2008 study suggested that the San may have been isolated from other original ancestral groups for as much as 50,000 to 100,000 years and later rejoined, re-integrating into the rest of the human gene pool.

During the early phases of European colonization, tens of thousands of Khoekhoe and San peoples lost their lives as a result of genocide, murder, physical mistreatment, and disease.

There were cases of “Bushman hunting” in which commandos (mobile paramilitary units or posses) sought to dispatch San and Khoekhoe in various parts of Southern Africa.

[37]: 2 Loss of land is a major contributor to the problems facing Botswana's indigenous people, including especially the San's eviction from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

[73] A licence was granted to Phytopharm, for development of the active ingredient in the Hoodia plant, p57 (glycoside), to be used as a pharmaceutical drug for dieting.

The terms of the agreement are contentious, because of their apparent lack of adherence to the Bonn Guidelines on Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit Sharing, as outlined in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

The San of the Kalahari were first brought to the globalized world's attention in the 1950s by South African author Laurens van der Post.

Van der Post grew up in South Africa, and had a respectful lifelong fascination with native African cultures.

Driven by a lifelong fascination with this "vanished tribe," Van der Post published a 1958 book about this expedition, entitled The Lost World of the Kalahari.

[76] His sister Elizabeth Marshall Thomas wrote several books and numerous articles about the San, based in part on her experiences living with these people when their culture was still intact.

A documentary on San hunting entitled, The Great Dance: A Hunter's Story (2000), directed by Damon and Craig Foster.

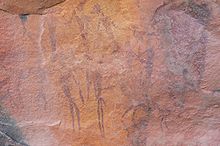

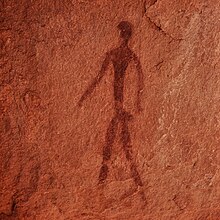

The presenter Nigel Spivey draws largely on the work of Professor David Lewis-Williams,[83] whose PhD was entitled "Believing and Seeing: Symbolic meanings in southern San rock paintings".

The film was directed by Jamie Uys, who returned to the San a decade later with The Gods Must Be Crazy, which proved to be an international hit.

By the time this movie was made, the ǃKung had recently been forced into sedentary villages, and the San hired as actors were confused by the instructions to act out inaccurate exaggerations of their almost abandoned hunting and gathering life.

In Peter Godwin's biography When A Crocodile Eats the Sun, he mentions his time spent with the San for an assignment.

Laurens van der Post's two novels, A Story Like The Wind (1972) and its sequel, A Far Off Place (1974), made into a 1993 film, are about a white boy encountering a wandering San and his wife, and how the San's life and survival skills save the white teenagers' lives in a journey across the desert.

Norman Rush's 1991 novel Mating features an encampment of Basarwa near the (imaginary) Botswana town where the main action is set.

1 Ladies' Detective Agency series, Mr. J. L. B. Matekoni, adopts two orphaned San children, sister and brother Motholeli and Puso.

In Christopher Hope's book Darkest England, the San hero, David Mungo Booi, is tasked by his fellow tribesmen with asking the Queen for the protection once promised, and to evaluate the possibility of creating a colony on the island.