Baseball card

Baseball cards are most often found in the Contiguous United States but are also common in Puerto Rico or countries such as Canada, Cuba, South Korea and Japan, where top-level leagues are present with a substantial fan base to support them.

In 1868, Peck and Snyder, a sporting goods store in New York, began producing trade cards featuring baseball teams.

Cards with similar images as the York Caramel set were produced in 1928 for four ice cream companies, Yuengling's, Harrington's, Sweetman and Tharp's.

In contrast to the economical designs standard in earlier decades, this card set featured bright, hand-colored player photos on the front.

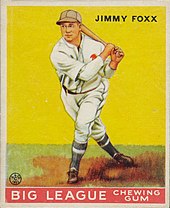

Goudey, National Chicle, Delong, and a handful of other companies were competitive in the bubble gum and baseball card market until World War II began.

For example, Kellogg's began to produce 3D-cards inserted with cereal and Hostess printed cards on packages of its baked goods.

TCMA published a baseball card magazine named Collectors Quarterly, which it used to advertise its set, offering it directly via mail order.

Upper Deck introduced several innovative production methods including tamper-proof foil packaging, hologram-style logos, and higher-quality card stock.

Eighteen-year-old employee, Tom Geideman, selected the players for the inaugural 1989 set proposing Griffey, a minor leaguer at the time, for the coveted #1 spot.

[39] Griffey had yet to make his major league debut with the Seattle Mariners, so in order to create his rookie card, an image of him in his San Bernardino Spirits uniform was altered.

[37] As of the summer of 2022, Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA) certified over 4,000 copies of the 1989 Ken Griffey Jr. rookie card were graded a 10, or Gem Mint status.

[37] Starting in 1997 with Upper Deck, companies began inserting cards with swatches of uniforms and pieces of game-used baseball equipment as part of a plan to generate interest.

Card companies obtained all manner of memorabilia, from uniform jerseys and pants, to bats, gloves, caps, and even bases and defunct stadium seats to feed this new hobby demand.

The process and cost of multi-tiered printings, monthly set issues, licensing fees, and player-spokesman contracts made for a difficult market.

At that time, the MLBPA limited the number of companies that would produce baseball cards to offset the glut in product, and to consolidate the market.

[37] Topps and Upper Deck are the only two companies that retained production licenses for baseball cards of major league players.

[43] Also, since the late 1990s, hobby retail shops and trade-show dealers found their customer base declining, with their buyers now having access to more items and better prices on the Internet.

A reported prankster inside the company had inserted a photo of Mickey Mantle into the Yankees' dugout and another showing a smiling President George W. Bush waving from the stands.

[44] In February 2007, one of the hobby's most expensive card, a near mint/mint professionally graded and authenticated T206 Honus Wagner, was sold to a private collector for $2.35 million.

Sets like 1909–1911 White Borders, 1910 Philadelphia Caramels, and 1909 Box Tops are most commonly referred to by their ACC catalog numbers (T206, E95, and W555, respectively).

That card was sold at auction for a new record price for all sports memorabilia in 2023 - $12,600,000, including buyer's premium - shattering the previous record for a baseball card (a T206 Honus Wagner, for $6,600,000 in 2021) and for sports memorabilia (the jersey Diego Maradona was wearing when he scored the infamous "hand of God" goal in the 1986 World Cup, for $9,300,000 in 2022).

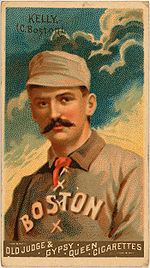

The earliest cards were targeted primarily at adults as they were produced and associated by photographers selling services and tobacco companies in order to market their wares.

For example, World War I suppressed baseball card production to the point where only a handful of sets were produced until the economy had transitioned away from wartime industrialization.

Struggling to raise funds, the MLBPA discovered that it could generate significant income by pooling the publicity rights of its members and offering companies a group license to use their images on various products.

Fleer even filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission alleging that Topps was engaged in unfair competition through its aggregation of exclusive contracts.

After continued discussions went nowhere, before the 1968 season, the union asked its members to stop signing renewals on these contracts, and offered Fleer the exclusive rights to market cards.

After several years of litigation, the court ordered the union to offer group licenses for baseball cards to companies other than Topps.

Fleer's legal victory was overturned after one season, but they continued to manufacture cards, substituting stickers with team logos for gum.

The full color cards were produced by Topps Republic of Ireland subsidiary company and contained explanations of baseball terms.

Subsequent baseball cards were released annually in boxed sets or foil packs until 1996 when declining interest saw production cease.