Bathing

In Hinduism, “Prataha Kaal” (the onset of day) or “Brahma Muhoortham” begins with the 4 am “snanam” or bath, and was considered extremely auspicious in ancient times.

The earliest findings of baths date from the mid-2nd millennium BC in the palace complex at Knossos, Crete, and the luxurious alabaster bathtubs excavated in Akrotiri, Santorini.

Ancient Rome developed a network of aqueducts to supply water to all large towns and population centers and had indoor plumbing, with pipes that terminated in homes and at public wells and fountains.

In the 6th to 8th centuries (in the Asuka and Nara periods) the Japanese absorbed the religion of Buddhism from China, which had a strong impact on the culture of the entire country.

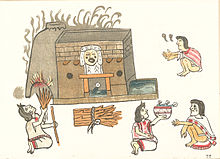

Bathing was not restricted to the elite, but was practised by all people; the chronicler Tomás López Medel wrote after a journey to Central America that "Bathing and the custom of washing oneself is so quotidian (common) amongst the Indians, both of cold and hot lands, as is eating, and this is done in fountains and rivers and other water to which they have access, without anything other than pure water..."[7] The Mesoamerican bath, known as temazcal in Spanish, from the Nahuatl word temazcalli, a compound of temaz ("steam") and calli ("house"), consists of a room, often in the form of a small dome, with an exterior firebox known as texictle (teʃict͜ɬe) that heats a small portion of the room's wall made of volcanic rocks; after this wall has been heated, water is poured on it to produce steam, an action known as tlasas.

Additionally, during the Renaissance and Protestant Reformation, the quality and condition of the clothing (as opposed to the actual cleanliness of the body itself) were thought to reflect the soul of an individual.

[18][19][20] In the sixteenth century, the popularity of public bathhouses in Europe sharply declined, perhaps due to the new plague of syphilis which made sexual promiscuity more risky, or stronger religious prohibitions on nudity surrounding the Protestant Reformation.

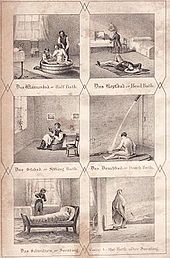

One of these was by Sir John Floyer, a physician of Lichfield, who, struck by the remedial use of certain springs by the neighbouring peasantry, investigated the history of cold bathing and published a book on the subject in 1702.

[25] The other work was a 1797 publication by Dr James Currie of Liverpool on the use of hot and cold water in the treatment of fever and other illness, with a fourth edition published not long before his death in 1805.

[27] A popular revival followed the application of hydrotherapy around 1829, by Vincenz Priessnitz, a peasant farmer in Gräfenberg, then part of the Austrian Empire.

[30] In Wörishofen (south Germany), Kneipp developed the systematic and controlled application of hydrotherapy for the support of medical treatment that was delivered only by doctors at that time.

His 10-week tour in Ireland included Limerick, Cork, Wexford, Dublin and Belfast,[31] over June, July and August 1843, with two subsequent lectures in Glasgow.

[13]: 2–14 [33] The popularity of wash-houses was spurred by the newspaper interest in Kitty Wilkinson, an Irish immigrant "wife of a labourer" who became known as the Saint of the Slums.

[34] In 1832, during a cholera epidemic, Wilkinson took the initiative to offer the use of her house and yard to neighbours to wash their clothes, at a charge of a penny per week,[13] and showed them how to use a chloride of lime (bleach) to get them clean.

[38] On 19 November 1844, it was decided that the working class members of society should have the opportunity to access baths, in an attempt to address the health problems of the public.

[40][41] By the mid-19th century, the English urbanised middle classes had formed an ideology of cleanliness that ranked alongside typical Victorian concepts, such as Christianity, respectability and social progress.

London water supply infrastructure developed through major 19th-century treatment works built in response to cholera threats, to modern large-scale reservoirs.

The half day off allowed time for the considerable labor of drawing, carrying, and heating water, filling the bath and then afterward emptying it.

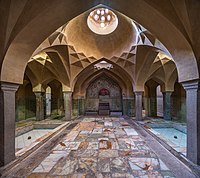

[49][50][51] Muslim bathhouses or hammams were historically found across the Middle East, North Africa, al-Andalus (Islamic Spain and Portugal), Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and in Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule.

[49][50][52] Archeological remains attest to the existence of bathhouses in the Islamic world as early as the Umayyad period (7th–8th centuries) and their importance has persisted up to modern times.

[50][51][52] In a modern hammam visitors undress themselves, while retaining some sort of modesty garment or loincloth, and proceed into progressively hotter rooms, inducing perspiration.

In 1856 Dr Richard Barter read Urquhart's book and worked with him to construct such a bath, intending to use it at his hydropathic establishment at St Ann(e)'s Hill, near Blarney, County Cork, Ireland.

[55] Barter realised that the human body could tolerate the more therapeutically effective higher temperatures in hot air which was dry rather than steamy.

The following year, the first public bath of its type to be built in mainland Britain since Roman times was opened in Manchester,[57] and the idea spread rapidly.

It reached London in July 1860, when Roger Evans, a member of one of Urquhart's Foreign Affairs Committees, opened a Turkish bath at 5 Bell Street, near Marble Arch.

[58] During the following 150 years, over 700 Turkish baths opened in the British Isles, including those built by municipal authorities as part of swimming pool complexes.

[63] Urquhart's influence was also felt outside the Empire when in 1861, Dr Charles H. Shepard opened the first Turkish baths in the United States at 63 Columbia Street, Brooklyn Heights, New York, most probably on 3 October 1863.

It is a means of achieving cleanliness by washing away dead skin cells, dirt, and soil and as a preventative measure to reduce the incidence and spread of disease.

[70] Bathing infants too often has been linked to the development of asthma or severe eczema according to some researchers, including Michael Welch, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics' section on allergy and immunology.

In the High Middle Ages, public baths were a popular subject of painting, with rather clear depictions of sexual advances, which probably were not based on actual observations.