Battle of Alexandria (30 BC)

The desertions continued, however, and, in early August, Octavian launched a second, ultimately successful, invasion of Egypt, after which Antony and his lover, Cleopatra, committed suicide.

But the triumvirate broke down when Octavian saw Caesarion, the professed son of Julius Caesar[1] and Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, as a major threat to his power.

After years of loyal cooperation with Octavian, Antony started to act independently, eventually arousing his rival's suspicion that he was vying to become sole master of Rome.

[citation needed] As a personal challenge to Octavian's prestige, Antony tried to get Caesarion accepted as a true heir of Caesar, even though the legacy did not mention him.

Antony complained that Octavian had exceeded his powers in deposing Lepidus, in taking over the countries held by Sextus Pompeius and in enlisting soldiers for himself without sending half to him.

Octavian complained that Antony had no authority to be in Egypt; that his execution of Sextus Pompeius was illegal; that his treachery to the king of Armenia disgraced the Roman name; that he had not sent half the proceeds of the spoils to Rome according to his agreement; and that his connection with Cleopatra and acknowledgment of Caesarion as a legitimate son of Caesar were a degradation of his office and a menace to himself.

Ahenobarbus seems to have wished to keep quiet, but on 1 January Sosius made an elaborate speech in favor of Antony, and would have proposed the confirmation of his act had it not been vetoed by a tribune.

In early August, Octavian, now severely outnumbering Antony, launched a second, ultimately successful attack by land from east and west, causing the city to fall.

Antony's other children would all rise to positions of relative power, and eventually would be direct ancestors to three Roman emperors: Claudius, Nero and Caligula.

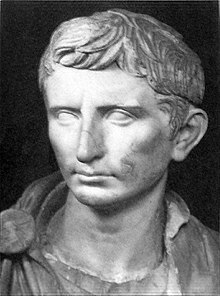

[9] At the age of thirty-three, Octavian had finally achieved the undisputed control of the Roman world which had been his unwavering ambition through fourteen years of civil war.

To this end, he had been responsible for death, destruction, confiscation, and unbroken misery on a scale quite unmatched in all the previous phases of Roman civil conflict over the past century, but he managed to maintain peace and ushered in a golden era for Rome until his death at age 75, though at the cost of Alexandrian independence and Roman blood.