Julius Caesar

While there, he travelled to Bithynia to collect naval reinforcements and stayed some time as a guest of the king, Nicomedes IV, though later invective connected Caesar to a homosexual relation with the monarch.

After the capture of Mytilene, Caesar transferred to the staff of Publius Servilius Vatia in Cilicia before learning of Sulla's death in 78 BC and returning home immediately.

[21] Afterward, Caesar attacked some of the Sullan aristocracy in the courts but was unsuccessful in his attempted prosecution of Gnaeus Cornelius Dolabella in 77 BC, who had recently returned from a proconsulship in Macedonia.

[24] His studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the Third Mithridatic War over the winter of 75 and 74 BC; Caesar is alleged to have gone around collecting troops in the province at the locals' expense and leading them successfully against Mithridates' forces.

Some of the Sullan nobles – including Quintus Lutatius Catulus – who had suffered under the Marian regime objected, but by this point depictions of husbands in aristocratic women's funerary processions was common.

[36] Four years after his aunt Julia's funeral, in 65 BC, Caesar served as curule aedile and staged lavish games that won him further attention and popular support.

[39] It is more likely that Caesar was merely restoring his family's public monuments – consistent with standard aristocratic practice and the virtue of pietas – and, over objections from Catulus, these actions were broadly supported by the Senate.

[46] Caesar also engaged in a collateral manner in the trial of Gaius Rabirius by one of the plebeian tribunes – Titus Labienus – for the murder of Saturninus in accordance with a senatus consultum ultimum some forty years earlier.

[50] Caesar won his election to the praetorship in 63 BC easily and, as one of the praetor-elects, spoke out that December in the Senate against executing certain citizens who had been arrested in the city conspiring with Gauls in furtherance of the conspiracy.

[53] During his year as praetor, Caesar first attempted to deprive his enemy Catulus of the honour of completing the rebuilt Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, accusing him of embezzling funds, and threatening to bring legislation to reassign it to Pompey.

He then brought in the Senate a bill – crafted to avoid objections to previous land reform proposals and any indications of radicalism – to purchase property from willing sellers to distribute to Pompey's veterans and the urban poor.

[75] Unable to overcome Cato's filibustering, he moved the bill before the people and, at a public meeting, Caesar's co-consul Bibulus threatened a permanent veto for the entire year.

[99] He was drawn further north responding to requests from Gallic tribes, including the Aedui, for aid against Ariovistus – king of the Suebi and a declared friend of Rome by the Senate during Caesar's own consulship – and he defeated them at the Battle of Vosges.

[104] He, however, withdrew from the island in the face of winter uprisings in Gaul led by the Eburones and Belgae starting in late 54 BC which ambushed and virtually annihilated a legion and five cohorts.

[117] Cicero was induced to oppose reassignment of Caesar's provinces and to defend a number of the allies' clients; his gloomy predictions of a triumviral set of consuls-designate for years on end proved an exaggeration when, only by desperate tactics, bribery, intimidation and violence were Pompey and Crassus elected consuls for 55 BC.

[124][125][126] At the start of 53 BC, Caesar sought and received reinforcements by recruitment and a private deal with Pompey before two years of largely unsuccessful campaigning against Gallic insurgents.

[135] As 50 BC progressed, fears of civil war grew; both Caesar and his opponents started building up troops in southern Gaul and northern Italy, respectively.

[148] This also was the core of his war justification: that Pompey and his allies were planning, by force if necessary (indicated in the expulsion of the tribunes[149]), to suppress the liberty of the Roman people to elect Caesar and honour his accomplishments.

[150] Around 10 or 11 January 49 BC,[151][152] in response to the Senate's "final decree",[153] Caesar crossed the Rubicon – the river defining the northern boundary of Italy – with a single legion, the Legio XIII Gemina, and ignited civil war.

Prevented from leaving the city by Etesian winds, Caesar decided to arbitrate an Egyptian civil war between the child pharaoh Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator and Cleopatra, his sister, wife, and co-regent queen.

[173] When Caesar landed at Antioch, he learnt that during his time in Egypt, the king of what is now Crimea, Pharnaces, had attempted to seize what had been his father's kingdom, Pontus, across the Black Sea in northern Anatolia.

Cato had marched to Africa[175] and there Metellus Scipio was in charge of the remaining republicans; they allied with Juba of Numidia; what used to be Pompey's fleet also raided the central Mediterranean islands.

Caesar would serve with Lepidus as consul in 46; he borrowed money for the war, confiscated and sold the property of his enemies at fair prices, and then left for Africa on 25 December 47 BC.

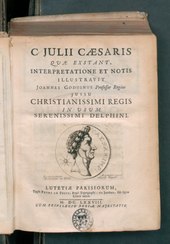

[197] Similarly extraordinary were a number of symbolic honours which saw Caesar's portrait placed on coins in Rome – the first for a living Roman[198][199] – with special rights to wear royal dress, sit atop a golden chair in the Senate, and have his statues erected in public temples.

The decisions on the normal operation of the state – justice, legislation, administration, and public works – were concentrated into Caesar's person without regard for or even notice given to the traditional institutions of the republic.

[206] The royal power of naming patricians was revived to benefit the families of his men[207] and the permanent courts' jury pools were also altered to remove the tribuni aerarii, leaving only the equestrians and senators.

[212] Many of his enemies during the civil wars were pardoned – Caesar's clemency was exalted in his propaganda and temple works – with the intent to cultivate gratitude and draw a contrast between himself and the vengeful dictatorship of Sulla.

[251] The terms of the will were also read to the public: it gave a generous donative to the plebs at large and left as principal heir one Gaius Octavius, Caesar's great-nephew then at Apollonia, and adopted him in the will.

[252] Resumption of the pre-existing republic proved impossible as various actors appealed in the aftermath of Caesar's death to liberty or to vengeance to mobilise huge armies that led to a series of civil wars.

Then, the plosive /k/ before front vowels began, due to palatalization, to be pronounced as an affricate, hence renderings like [ˈtʃɛːzar] in Italian and [ˈtseːzaʁ] in German regional pronunciations of Latin, as well as the title of Tsar.