Battle of Arsuf

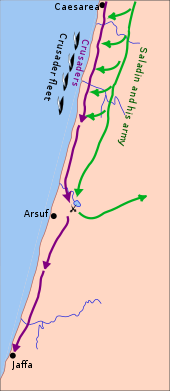

In an attempt to disrupt the cohesion of the Crusader army as they mobilized, the Ayyubid force launched a series of harassing attacks that were ultimately unsuccessful at breaking their formation.

A large part of the Egyptian fleet had been captured at the fall of Acre, and with no threat from this quarter he could march south along the coast with the sea always protecting his right flank.

Aware of the ever-present danger of enemy raiders and the possibility of hit-and-run attacks, he kept the column in tight formation with a core of twelve mounted regiments, each with a hundred knights.

[8][9] Though provoked and tormented by the skirmish tactics of Saladin's archers, Richard's generalship ensured that order and discipline were maintained under the most difficult of circumstances.

[10] Baha al-Din ibn Shaddad, the Muslim chronicler and eyewitness, describes the march: "The Moslems discharged arrows at them from all sides to annoy them, and force them to charge: but in this they were unsuccessful.

He saw Frankish infantrymen with from one to ten arrows sticking from their armoured backs marching along with no apparent hurt, whilst the crossbows struck down both horse and man amongst the Muslims.

[13] Efforts to burn crops and deny the countryside to the Frankish army were largely ineffective as it could be continuously provisioned from the fleet, which moved south parallel with it.

Fortuitously for Saladin, the Crusaders had to traverse one of the few forested regions of Palestine, the "Wood of Arsuf", which ran parallel to the sea shore for more than 20 km (12 mi).

[16][17][18] The Crusaders traversed half of the forest with little incident, and they rested on 6 September with their camp protected by the marsh lying inland of the mouth of the river Nahr-el-Falaik, called by them Rochetaillée.

His plan appears to have been to allow the Frankish van and centre to proceed, in the hope that a fatal gap might be created between them and the more heavily engaged rearmost units.

[23] At dawn on 7 September, as Richard's forces began moving out of camp enemy scouts were visible in all directions, hinting that Saladin's whole army lay hidden in the woodland.

They had the most experience of fighting in the East, were arguably the most disciplined, and were the only formations which included Turcopole cavalry who fought like the Turkish horse archers of the Ayyubid army.

They were followed by three units composed of Richard's own subjects, the Angevins and Bretons, then the Poitevins including Guy of Lusignan, titular King of Jerusalem, and lastly the English and Normans who had charge of the great standard mounted on its waggon.

Additionally, a small troop, under the leadership of Henry II of Champagne, was detached to scout towards the hills, and a squadron of picked knights under King Richard and Hugh of Burgundy, the leader of the French contingent, was detailed to ride up and down the column checking on Saladin's movements and ensuring that their own ranks were kept in order.

Behind these were the ordered squadrons of armoured heavy cavalry: Saladin's mamluks (also termed ghulams), Kurdish troops, and the contingents of the emirs and princes of Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia.

[27] In an attempt to destroy the cohesion of the Crusader army and unsettle their resolve, the Ayyubid onslaught was accompanied by the clashing of cymbals and gongs, trumpets blowing and men screaming war-cries.

[28] "In truth, our people, so few in number, were hemmed in by the multitudes of the Saracens, that they had no means of escape, if they tried; neither did they seem to have valour sufficient to withstand so many foes, nay, they were shut in, like a flock of sheep in the jaws of wolves, with nothing but the sky above, and the enemy all around them.

[31] Saladin, eager to urge his soldiers into closer combat, personally entered the fray, accompanied by two pages leading spare horses.

Richard knew that the charge of his knights needed to be reserved until the Ayyubid army was fully committed, closely engaged, and the Saracens' horses had begun to tire.

[38] The traditionally accepted version of events is that Garnier de Nablus and the Hospitaller cavalry charged when goaded beyond endurance, and did so in direct disobedience of Richard's orders.

To the soldiers of Saladin's army, as Baha al-Din noted, the sudden change from passivity to ferocious activity on the part of the Crusaders was disconcerting, and appeared to be the result of a preconceived plan.

Noting the disintegration of the right wing he finally sought Saladin's personal banners, but found only seventeen members of the bodyguard and a lone drummer still with them.

[44][45] Being aware that an over-rash pursuit was the greatest danger when fighting armies trained in the fluid tactics of the Turks, Richard halted the charge after about 1.5 km (1 mi) had been covered.

[46][43] Leading by example, Richard was in the heart of the fighting, as the Itinerarium describes: There the king, the fierce, the extraordinary king, cut down the Turks in every direction, and none could escape the force of his arm, for wherever he turned, brandishing his sword, he carved a wide path for himself: and as he advanced and gave repeated strokes with his sword, cutting them down like a reaper with his sickle, the rest, warned by the sight of the dying, gave him more ample space, for the corpses of the dead Turks which lay on the face of the earth extended over half a mile.

Ambroise mentions that Richard's troops counted several thousand bodies of dead Saracen soldiers on the field of battle after the rout.

Baha al-Din records only three deaths amongst the leaders of the Ayyubid army: Musek, Grand-Emir of the Kurds, Kaimaz el Adeli and Lighush.

The only Crusader leader of note to die in the battle was James d'Avesnes; a French knight of whom Ambroise made the claim that he cut down 15 Saracen cavalrymen before being killed.

A contemporary opinion stated that, had Richard been able to choose the moment to unleash his knights, rather than having to react to the actions of an insubordinate unit commander, the Crusader victory might have been much more effective.

Both sides had become exhausted by the struggle, Richard needed to return to Europe in order to protect his patrimony from the aggression of Philip of France, and Palestine was in a ruinous state.