Saint George

Of Cappadocian Greek origin, he became a member of the Praetorian Guard for Roman emperor Diocletian, but was sentenced to death for refusing to recant his Christian faith.

The widespread veneration for St George as a soldier saint from early times had its centre in Palestine at Diospolis, now Lydda (known as Lod to Israelis).

[7][16] The earliest text which preserves fragments of George's narrative is in a Greek hagiography which is identified by Hippolyte Delehaye of the scholarly Bollandists to be a palimpsest of the 5th century.

[17] An earlier work by Eusebius, Church history, written in the 4th century, contributed to the legend but did not name George or provide significant detail.

[18] The work of the Bollandists Daniel Papebroch, Jean Bolland, and Godfrey Henschen in the 17th century was one of the first pieces of scholarly research to establish the saint's historicity, via their publications in Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca.

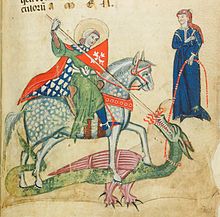

[31] Saint George's encounter with a dragon, as narrated in the Golden Legend, would go on to become very influential, as it remains the most familiar version in English owing to William Caxton's 15th-century translation.

When the king tried to starve him, he touched a piece of dry wood brought by a woman and turned it green, with varieties of fruits and vegetables growing from it.

[38] The veneration of George spread from Syria Palaestina through Lebanon to the rest of the Byzantine Empire – though the martyr is not mentioned in the Syriac Breviarium[27] – and the region east of the Black Sea.

The first description of Lydda as a pilgrimage site where George's relics were venerated is De Situ Terrae Sanctae by the archdeacon Theodosius, written between 518 and 530.

The chivalric military Order of Sant Jordi d'Alfama was established by king Peter the Catholic from the Crown of Aragon in 1201, Republic of Genoa, Kingdom of Hungary (1326), and by Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor.

The chronicler Jean Froissart observed the English invoking George as a battle cry on several occasions during the Hundred Years' War.

The establishment of George as a popular saint and protective giant[49] in the West, that had captured the medieval imagination, was codified by the official elevation of his feast to a festum duplex[50] at a church council in 1415, on the date that had become associated with his martyrdom, 23 April.

Deranged persons of all the three faiths are taken thither and chained in the court of the chapel, where they are kept for forty days on bread and water, the Eastern Orthodox priest at the head of the establishment now and then reading the Gospel over them, or administering a whipping as the case demands.

"[58][59] The Encyclopædia Britannica quotes G. A. Smith in his Historic Geography of the Holy Land, p. 164, saying: "The Mahommedans who usually identify St. George with the prophet Elijah, at Lydda confound his legend with one about Christ himself.

[53] According to Elizabeth Anne Finn's Home in the Holy land (1866):[62] St George killed the dragon in this country; and the place is shown close to Beyroot.

It is singular that the Moslem Arabs adopted this veneration for St George, and send their mad people to be cured by him, as well as the Christians, but they commonly call him El Khudder – The Green – according to their favourite manner of using epithets instead of names.

Gray horses are called green in Arabic.The mosque of Nabi Jurjis, which was restored by Timur in the 14th century, was located in Mosul and supposedly contained the tomb of George.

[68] The story of Saint George slaying the dragon is interpreted allegorically, representing the triumph of good over evil and the protection of the faithful from harm.

[73] On 27 April after the flag hoisting ceremony by the parish priest, the statue of the saint is taken from one of the altars and placed at the extension of the church to be venerated by devotees till 14 May.

Tradition says that the spots at the Moon's surface represent the miraculous saint, his horse and his sword slaying the dragon and ready to defend those who seek his help.

Legend has it that victory eventually fell to the Christian armies when George appeared to them on the battlefield, helping them secure the conquest of the city of Huesca which had been under the Muslim control of the Taifa of Zaragoza.

With the Aragonese spirits flagging, it is said that George descending from heaven on his charger and bearing a dark red cross, appeared at the head of the Christian cavalry leading the knights into battle.

Interpreting this as a sign of protection from God, the Christian militia returned emboldened to the battle field, more energised than ever, convinced theirs was the banner of the one true faith.

After the fall of Huesca, King Pedro aided the military leader and nobleman, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, otherwise known as El Cid, with a coalition army from Aragon in the long conquest of the Kingdom of Valencia.

Tales of King Pedro's success at Huesca and in leading his expedition of armies with El Cid against the Moors, under the auspices of George on his standard, spread quickly throughout the realm and beyond the Crown of Aragon, and Christian armies throughout Europe quickly began adopting George as their protector and patron, during all subsequent Crusades to the Holy Lands.

By 1117, the military order of Templars adopted the Cross of St. George as a simple, unifying sign for international Christian militia embroidered on the left hand side of their tunics, placed above the heart.

[96][97][98] It became fashionable in the 15th century, with the full development of classical heraldry, to provide attributed arms to saints and other historical characters from the pre-heraldic ages.

[99] In 1348, Edward III of England chose George as the patron saint of his Order of the Garter, and also took to using a red-on-white cross in the hoist of his Royal Standard.

Thus, a 2003 Vatican stamp (issued on the anniversary of the Saint's death) depicts an armoured George atop a white horse, killing the dragon.

Immediately on the publication of the decree against the churches in Nicomedia, a certain man, not obscure but very highly honored with distinguished temporal dignities, moved with zeal toward God, and incited with ardent faith, seized the edict as it was posted openly and publicly, and tore it to pieces as a profane and impious thing; and this was done while two of the sovereigns were in the same city,—the oldest of all, and the one who held the fourth place in the government after him.