Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River

Anticipating this reaction, the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) Commander Peng Dehuai planned a counteroffensive, dubbed the "Second Phase Campaign", against the advancing UN forces.

Hoping to repeat the success of the earlier First Phase Campaign, the PVA 13th Army[nb 2] first launched a series of surprise attacks along the Ch'ongch'on River Valley on the night of November 25, 1950, at the western half of the Second Phase Campaign[nb 3] (Chinese: 第二次战役西线; pinyin: Dì'èrcì Zhànyì Xīxiàn), effectively destroying the Eighth United States Army's right flank, while allowing PVA forces to move rapidly into UN rear areas.

[12] Alarmed by this development, Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong ordered the PVA to intervene in Korea and to launch the First Phase Campaign against the UN forces.

[23] Encouraged by the fact that the UN did not know their true numbers, PVA Commander Peng Dehuai outlined the Second Phase Campaign, a counteroffensive aimed at pushing the UN forces back to a line halfway between Ch'ongch'on River and Pyongyang.

[6] As a part of a deception plan to further reinforce the weak appearance of PVA forces, Peng ordered all units to rapidly retreat north while releasing POWs along the way.

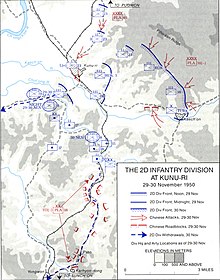

[31] A road runs south from Kunu-ri into Sunchon and eventually into Pyongyang, and it would later become the main retreat route for the UN forces stationed at the center of the front line.

[32] The hilly terrain on the northern bank of the Ch'ongch'on River formed a defensive barrier that allowed the Chinese to hide their presence while dispersing the advancing UN forces.

[37] The three UN Corps advanced cautiously in a continuous front line in order to prevent more ambushes similar to the PVA First Phase Campaign,[37] but the lack of manpower stretched the UN forces to the limit.

[37] Except for the strong PVA resistance against ROK II Corps, the Eighth Army met little opposition, and the line between Chongju to Yongwon was occupied on the night of the November 25.

[40] Boosted by a Thanksgiving feast with roasted turkeys on the eve of the advance, the morale was high among the UN ranks, and home by Christmas and Germany by spring was in everyone's mind.

A rifle company from the US IX Corps, for example, started its advance with most of the helmets and bayonets thrown away, and there were on average less than one grenade and 50 rounds of ammunition carried per man.

[50] The primitive logistics system had also allowed the PVA to maneuver over the rough hilly terrains, thus enabled them to by-pass the UN defenses and to surround the isolated UN positions.

[61] As the ROK were preparing their defensive positions on the dusk of November 25, the two PVA corps were mobilizing for a decisive counterattack against the Eighth Army's right flank.

[86][90] The surviving PVA troops drifted eastward and occupied a hill named Chinaman's Hat,[86] enabling them to overlook the entire 23rd Infantry Regiment's positions.

[92] Adding to the confusion, Chinese reconnaissance teams lured the US forces into exposing their positions,[93] and the resulting PVA counter-fire caused the loss of the G Company on the 38th Infantry Regiment's center.

[81] Before Keiser's order was complete on November 28, Walker instructed Major General John B. Coulter of IX Corps to set up a new defensive line at Kunu-ri — 20 mi (32 km) south of the US 2nd Infantry Division.

[113] When Task Force Dolvin proceeded to capture a series of hills north of Ipsok on the next day,[115] PVA resistance started to stiffen.

[137] Although PVA booby traps and mortar fire tried to delay the ROK forces along the way, the 1st Infantry Division still managed to envelop the town by the dusk of November 24.

[137] But unknown to the ROK forces, the 1st Infantry Division was marching into a PVA assembly area, and the resistance around Taechon immediately increased as the result.

[137] As the morning came on November 27, the PVA troops around Taechon did not stop their assault even under punishing UN air strikes, and some of the attacks spilled into US 24th Infantry Division's area.

[32] In an effort to stabilize the front on November 28, Walker ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to retreat from Kujang-dong and to set up a new defensive line at Kunu-ri.

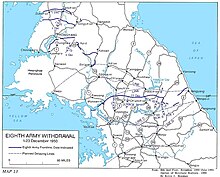

[164] After the conference at November 29, Walker ordered all Eighth Army units to retreat to a new line around Sunchon, 30 mi (48 km) south of Kunu-ri.

[168] Upon noticing this development, Brigadier General Tahsin Yazıcı of the Turkish Brigade ordered a withdrawal,[168] leaving the right flank of the 38th Infantry Regiment completely uncovered.

[142] At the same day, Walker shifted the Eighth Army's line eastward by attaching the US 1st Cavalry Division and the Anglo-Australian 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade to US IX Corps.

[177] Under Gay's order, the 7th Cavalry Regiment withdrew southwest to the town of Sinchang-ni on the morning of November 29, and the PVA resumed the drive southward.

[32][154] Upon receiving the news on November 29, 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, part of 27th Brigade, tried to clear the valley from the south, but the attack was halted due to the lack of heavy weapons.

[184] Keiser sent the Reconnaissance Company and the remnants of the 9th Infantry Regiment to dislodge the Chinese, but the roadblock held firm even with a platoon of tanks attacking it.

[196] As the 2nd Infantry Division entered the valley, later known as the "Gauntlet",[2] the PVA machine guns delivered punishing fire while mortar shells saturated the road.

[224] Walker died two days before the Christmas of 1950 when a truck driven by a ROK soldier collided with his jeep, and Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway assumed the command of the US Eighth Army.

[226] Both historian Clay Blair and Colonel Paul Freeman believed that the Turkish Brigade was "overrated, poorly led green troops" who "broke and bugged out", and blamed them for not protecting on the right flank of the US Eighth Army.

Chinese and

Soviet forces

• South Korean, U.S.,

Commonwealth

and United Nations

forces