Battle of Chickamauga

Chattanooga was a vital rail hub (with lines going north toward Nashville and Knoxville and south toward Atlanta), and an important manufacturing center for the production of iron and coke, located on the navigable Tennessee River.

[21] James Mooney, in Myths of the Cherokee, wrote that Chickamauga is the more common spelling for Tsïkäma'gï, a name that "has no meaning in their language" and is possibly "derived from an Algonquian word referring to a fishing or fish-spearing place... if not Shawano it is probably from the Creek or Chickasaw.

By early August, Halleck was frustrated enough with Rosecrans's delay that he ordered him to move forward immediately and to report daily the movement of each corps until he crossed the Tennessee River.

His men pounded on tubs and sawed boards, sending pieces of wood downstream, to make the Confederates think that rafts were being constructed for a crossing north of the city.

Braxton Bragg hoped to trap Negley by attacking through the cove from the northeast, forcing the Union division to its destruction at the cul-de-sac at the southwest end of the valley.

Early on the morning of September 10, Bragg ordered Polk's division under Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman to march 13 miles southwest into the cove and strike Negley's flank.

Hill claimed that Bragg's orders reached him very late and began offering excuses for why he could not advance—Cleburne was sick in bed and the road through Dug Gap was obstructed by felled timber.

Wilder, concerned about his left flank after Minty's loss of Reed's Bridge, withdrew and established a new blocking position east of the Lafayette Road, near the Viniard farm.

Strange and wonderful opportunities would loom out of the leaves, vines, and gunsmoke, be touched and vaguely sensed, and then fade away again into the figurative fog of confusion that bedeviled men on both sides.

Rosecrans's movement of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's XIV Corps the previous day put the left flank of the Army of the Cumberland farther north than Bragg expected when he formulated his plans for an attack on September 20.

[52] The Battle of Chickamauga opened almost by accident, when pickets from Col. Daniel McCook's brigade of Granger's Reserve Corps moved toward Jay's Mill in search of water.

Stewart encountered Wright's retreating brigade at the Brock farm and decided to attack Van Cleve's position on his left, a decision he made under his own authority.

Gen. John Turchin's brigade (Reynolds's division) counterattacked and briefly held off Sheffield, but the Confederates had caused a major penetration in the Federal line in the area of the Brotherton and Dyer fields.

Hood's and Johnson's men, pushing strongly forward, approached so close to Rosecrans's new headquarters at the tiny cabin of Widow Eliza Glenn that the staff officers inside had to shout to make themselves heard over the sounds of battle.

Polk was ordered to initiate the assault on the Federal left at daybreak, beginning with the division of Breckinridge, followed progressively by Cleburne, Stewart, Hood, McLaws, Bushrod, Johnson, Hindman, and Preston.

As he found the left flank of the Union line, Breckinridge realigned his two brigades to straddle the LaFayette Road to move south, threatening the rear of Thomas's Kelly field salient.

[76] The attack on the Confederate right flank had petered out by noon, but it caused great commotion throughout Rosecrans's army as Thomas sent staff officers to seek aid from fellow generals along the line.

Receiving the message on the west end of the Dyer field, Rosecrans, who assumed that Brannan had already left the line, desired Wood to fill the hole that would be created.

His chief of staff, James A. Garfield, who would have known that Brannan was staying in line, was busy writing orders for parts of Sheridan's and Van Cleve's divisions to support Thomas.

Longstreet's force of 10,000 men, primarily infantry, was similar in number to those he sent forward in Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg, and some historians judge that he learned the lessons of that failed assault by providing a massive, narrow column to break the enemy line.

William Glenn Robertson, however, contends that Longstreet's deployment was "happenstance", and that the general's after-action report and memoirs do not demonstrate that he had a grand, three-division column in mind.

The resolute and impetuous charge, the rush of our heavy columns sweeping out from the shadow and gloom of the forest into the open fields flooded with sunlight, the glitter of arms, the onward dash of artillery and mounted men, the retreat of the foe, the shouts of the hosts of our army, the dust, the smoke, the noise of fire-arms—of whistling balls and grape-shot and of bursting shell—made up a battle scene of unsurpassed grandeur.

Gen. Arthur Manigault, crossed the field east of the Widow Glenn's house when Col. John T. Wilder's mounted infantry brigade, advancing from its reserve position, launched a strong counterattack with its Spencer repeating rifles, driving the enemy around and through what became known as "Bloody Pond".

In the time that Wilder took to calm down the secretary and arrange a small detachment to escort him back to safety, the opportunity for a successful attack was lost and he ordered his men to withdraw to the west.

Despite all the furious activity on Snodgrass Hill, Longstreet was exerting little direction on the battlefield, enjoying a leisurely lunch of bacon and sweet potatoes with his staff in the rear.

Bragg knew, however, that his success on the southern end of the battlefield was merely driving his opponents to their escape route to Chattanooga and that the opportunity to destroy the Army of the Cumberland had evaporated.

On the Confederate side, Bragg began to wage a battle against the subordinates he resented for failing him in the campaign: Hindman for his lack of action in McLemore's Cove and Polk for his late attack on September 20.

[105] Harold Knudsen, a combat veteran and historian, contends that Chickamauga was the first major Confederate effort to use the "interior lines of the nation" to transport troops between theaters with the aim of achieving a period of numerical superiority and taking the initiative in the hope of gaining decisive results in the West.

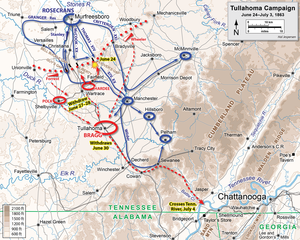

If a major victory erasing the Union gains of the Tullahoma Campaign and a winning of the strategic initiative could be achieved in late 1863, any threat to Atlanta would be eliminated for the near future.

Relief forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant broke Bragg's grip on the city, sent the Army of Tennessee into retreat, and opened the gateway to the Deep South for Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's 1864 Atlanta Campaign.