Battle of Fayetteville (1862)

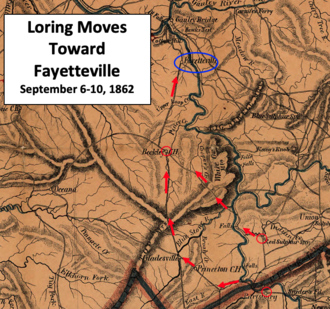

Confederate leadership found out about the depleted force, and sent Loring to drive the remaining Union soldiers out of the Kanawha Valley.

[4] The American Civil War began in 1861, and Union forces gained control of a large portion of southwestern Virginia, including the Kanawha Valley.

[12][Note 2] On August 14, 1862, Cox began moving his Kanawha Division to Washington as reinforcement for Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia.

[14] Exceptions to Cox's orders were about 5,000 troops left behind and put under the command of Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn, who was headquartered at Gauley Bridge.

[16] Most of the Union troops in the region were stationed at posts surrounding the community of Gauley Bridge, which was located at the eastern-most point of the Kanawha Valley.

[47] On August 22, he began the execution of his plan by sending north a cavalry force commanded by Brigadier General Albert G.

[49] Loring's force actually consisted of about 5,000 men instead the rumored 10,000, but he expected to add to it by recruiting and organizing existing local militias.

[16][Note 6] The news of Loring's large force in the south, plus the possibility of Confederate cavalry between Lightburn and Ohio, reached Union camps in early September.

[53] It returned to Virginia on the next day, reunited with a detachment, and arrived at the small Kanawha River community of Buffalo that evening.

[57][Note 7] That evening, they camped at McCoy's Mill (now Glen Jean, West Virginia), which was about nine miles (14 km) south of Siber's 1,200-man brigade at Fayetteville.

The remaining portion of Loring's army, led by Williams' Brigade, would make a frontal attack via the Princeton-Raleigh Road.

Wagon trains began moving supplies from Fayetteville to Gauley Bridge via Montgomery Ferry, and three companies from the 37th Ohio Infantry were sent south to reinforce pickets on the turnpike to Raleigh Court House.

[24] During this time, Lightburn ordered three companies of the 4th Loyal Virginia Infantry to move from Gauley Bridge to support Siber at Fayetteville.

Wharton decided to re-position his force so that it could cut off Siber's route of retreat along the pike north to Montgomery's Ferry.

A 24 pounder howitzer, which had been brought forward earlier at double-quick pace from Echols' Brigade, was added to the artillery pieces on the hill.

[68] The Union right and rear was protected by six companies from the 34th Ohio Infantry, and it used a howitzer to attack the Confederate flanking force before it had finalized its deployment in the woods.

The Confederate frontal attack included at least five charges across open fields against the fortified Union soldiers of the 37th Ohio Infantry.

Five companies of the 47th Ohio Infantry Regiment were sent across the river to Cotton Mountain, where they could offer assistance if Siber needed to retreat.

[80] Further north, the small Confederate cavalry force originally sent to cut communications had fled Cotton Hill because of Union infantry arriving in the area.

[81] Late that evening, Hoffman's cavalry was sent to Loup Creek to block and guard roads that led to the Kanawha River.

[79] Between 1:00 and 2:00 am on September 11, Siber began to withdraw using the Cotton Hill route to the Kanawha River that had been used by Captain Vance hours earlier.

[83] Lightburn's Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel Samuel A. Gilbert, left a detachment with artillery at Montgomery's Ferry to support Siber's retreat.

[87] Shunning a route along the Kanawha River where he could be intercepted by Confederate cavalry led by Jenkins, Lightburn took a road north to Ripley.

[86] In early October, Cox was promoted to major general and sent back to retake the Kanawha River Valley.

[90] By the end of October, Union forces retook control of the Kanawha Valley—including Charleston, Gauley Bridge, and Fayetteville.

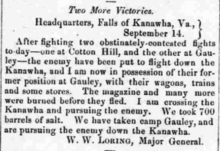

[94] On September 14, Loring sent a general order congratulating his army "on its successive victories over the enemy at Fayette Court-House, Cotton Hill, and Charleston.

The river would have been impassable, for all the ferry-boats were in the keeping of our men on the right bank, and Loring would not dare pass down the valley leaving a fortified post on the line of communications by which he must return.

[Note 9] Siber's report did not list casualties, although he wrote that the "losses of the Thirty-seventh Regiment in these combats were insignificant in proportion to those of the Thirty-fourth, by reason of their having occupied the breastworks.

"[101] Based on historian Terry Lowry's research, Union casualties were 16 killed, 67 wounded, 46 missing, 6 captured, and 2 died from disease.

[79] These figures are from Loring's medical director who reported on September 15, and it was noted that the count for wounded only included those that could no longer move with the army.