Infantry in the American Civil War

The infantry in the American Civil War comprised foot-soldiers who fought primarily with small arms and carried the brunt of the fighting on battlefields across the United States.

The conventional narrative is that officers adhered stubbornly to the tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, in which armies employed linear formations and favored open fields over the usage of cover.

"[1] At the start of the war, the entire United States Army consisted of 16,367 men of all branches, with infantry representing the vast majority of this total.

These organizations were more prevalent in the South, where hundreds of small local militia companies existed to protect against slave insurrections.

[7][9] The official structure for regiments was not always followed: the 66th Georgia for example constituted 1,500 soldiers organized into thirteen companies at its formation, while the 14th Indiana was formed with 1,134 men.

[11] Its authorized strength was approximately 100 soldiers, led by a captain who was assisted by a couple of lieutenants and several non-commissioned officers (NCOs).

Regimental staff officers were chosen from among the unit's lieutenants, while higher formations were to have a representative from the armies' respective War Departments.

Either civilian workers had to be hired or infantry soldiers detailed to handle these functions; the former tended to be unreliable while the latter lessened the combat effectiveness of their units.

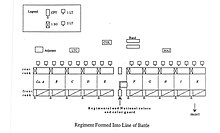

The core of these tactics was organizing soldiers into ranks and files in order to form a regiment into a line of battle or column.

[24] Of particular tactical importance was the usage of skirmishers, which historian Earl J. Hess argues reached its apogee during the Civil War.

Successive lines were best spaced out a couple hundred yards from each other so that they were far enough away to avoid being hit by the same fire yet close enough to provide support.

However, the presence of thick woodlands (which might account for as much as half of the area of a given Civil War battlefield) could quickly render even veteran units confused and disorganized.

[29] Infantry tactics in the Civil War had been developed around the use of the smoothbore musket, an inherently inaccurate weapon which (when combined with poor training and the general excitability of battle) was only effective at ranges of forty to sixty yards.

[30][3] However the Civil War saw the widespread usage of rifled muskets which, utilizing the Minié ball, were capable of accurately hitting targets at ranges of up to 500 yards.

[21] After the war, many veterans complained of an inappropriate devotion to Napoleonic tactics, conducting frontal assaults in tightly-packed formations and the casualties it would inevitably cause.

[31] Such criticisms were picked up by later historians such as Edward Hagerman, writing that the rifled musket doomed the frontal assault and led to the introduction of trench warfare.

Allen Guelzo points out two technological limitations which reduced the rifled musket's effective range, the first being its continued use of black powder.

The billowing clouds of smoke created from firing these weapons could become so thick as to reduce visibility to "less than fifty paces" and prevent accuracy at range.

The second is that the unique ballistic properties of the Minié ball meant that it followed a curved trajectory which required a well-trained shooter to utilize it at range.

In another, a soldier of the 1st South Carolina remarked that the chief casualties from an intense firefight conducted at one hundred yards were the needles and pinecones from the trees above them.

Instead he argues their increasing prevalence during the war was due to psychological reasons: a more risk-averse populace combined with officers influenced by the defensive-oriented teachings of men like Dennis Hart Mahan.

An increase in volume of fire rather than range may have necessitate a change in tactics, but the breechloader and repeating firearms which promised to do so were simply not available in sufficient quantities until well after the war.

[21] The standard weapon of infantry on both sides of the Civil War was the rifle musket, of which the Springfield Model 1861 and its derivatives was the most common.

[38][40] However, soldiers in the Civil War could be armed with a variety of weapons, particularly in the early days when neither side was well equipped for the fight ahead.

[38][39] One primary account of the typical infantryman came from James Gall, a representative of the United States Sanitary Commission, who observed Confederate infantrymen of Maj. Gen. Jubal A.

With the exception of some volunteer regiments receiving extra funding from their state or wealthy commander, the small numbers of rapid-fire weapons in service with US infantrymen, often skirmishers, were mostly purchased privately by soldiers themselves.

[44] Despite President Lincoln's enthusiasm for these types of weapons, the mass adoption of repeating rifles for the infantry was resisted by some senior Union officers.

During the Battle of Hoover's Gap, Wilder's Spencer-armed and well-fortified brigade of 4,000 men held off 22,000 attacking Confederates, and inflicted 287 casualties for only 27 losses.

[46] Even more striking, during the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, his Spencer-armed brigade launched a counterattack against a much larger Confederate division overrunning the Union's right flank.

Thanks in large part to the Lightning Brigade's superior firepower, they repulsed the Confederates and inflicted over 500 casualties, while suffering only 53 losses.