Battle of Five Forks

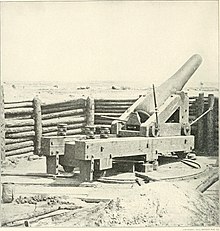

The Union force inflicted over 1,000 casualties on the Confederates and took up to 4,000 prisoners[notes 1] while seizing Five Forks, the key to control of the South Side Railroad, a vital supply line and evacuation route.

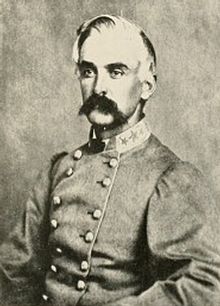

Owing to an acoustic shadow in the woods, Pickett and cavalry commander Major General Fitzhugh Lee did not hear the opening stage of the battle, and their subordinates could not find them.

[notes 2] Meanwhile, the Union held Five Forks and the road to the South Side Railroad, causing General Lee to abandon Petersburg and Richmond, and begin his final retreat.

[33][34] Before dawn on March 29, 1865, Warren's V Corps moved west of the Union and Confederate lines while Sheridan's cavalry took a longer, more southerly route toward Dinwiddie Court House.

Wise and Colonel Martin L. Stansel in lieu of the ill Young Marshall Moody,[46][48][49] reinforced by the brigades of Brigadier Generals Samuel McGowan and Eppa Hunton, attack the exposed Union line.

[64] On March 30, 1865, in driving rain, Sheridan sent Union cavalry patrols from Brigadier General Thomas Devin's division to seize Five Forks, the key junction for reaching the South Side Railroad.

[82][84][85] Custer set up another defensive line about 0.75 miles (1.21 km) north of Dinwiddie Court House, which together with Smith's and Gibbs's brigades, held off the attack by Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee until darkness ended the battle.

[88] Historian A. Wilson Greene has written that the best estimate of Confederate casualties in the Dinwiddie Court House engagement is 360 cavalry, 400 infantry, 760 total killed and wounded.

[102] When Grant then notified Sheridan that the V Corps and Ranald Mackenzie's division from the Union Army of the James had been ordered to his support, he gratuitously and without any basis said that Warren should reach him "by 12 tonight.

[129] When Pickett became aware that Union infantry divisions were arriving near his flank at about 10:00 pm, he withdrew to his modest log and dirt defensive line about 1.75 miles (2.8 km) north at Five Forks.

[notes 7][133]Historian Edward G. Longacre discounts the reliability of the report of this message, saying it was recalled 30 years later by Pickett's widow, who tended to exaggerate, distort and falsify her husband's records.

[134] He wrote that Pickett's report only mentions Lee's direction to protect the road to Ford's Depot and that no copy of the message has ever been found, which historian Douglas Southall Freeman also had noted in 1944.

He only knew he was to align the V Corps with the right flank of Devin's division and have them positioned as a turning column a short distance from White Oak Road and about 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Five Forks.

[174][175] Sheridan felt that Warren was not exerting himself to get the corps into position and stated in his after action report that he was anxious for the attack to begin as the sun was getting low and there was no place to entrench.

[185] The dispersal of Roberts's command meant that Pickett was cut off and if any reinforcements were sent, they would need to fight their way through on White Oak Road to reach his position or take a very circuitous route.

[190][191] Warren soon realized that the V Corps had crossed White Oak Road east of the left of the Confederate line and Crawford's division was starting to diverge from Ayres's.

[203] He was fired upon when he reached a local landmark, the "Chimneys",[notes 15] about 800 yards (730 m) north of the end of the Confederate refused line, by the volleys that caused Gwyn's brigade to recoil.

[204] Colonel Jonathan Tarbell brought up a battalion of the 91st New York Infantry Regiment which drove out Munford's men and allowed Kellogg's brigade to resume their move to the west.

[205] Griffin had not paused with the victory at the second defensive line but continued to advance to Five Forks where he met the dismounted troopers of Pennington's and Fitzhugh's brigades who had just broken through the Confederate fortifications.

[188] Fitzhugh Lee and Pickett decided that since they could not hear an attack, due as it turned out to the thick pine forest and heavy atmosphere between the camp and Five Forks and an acoustic shadow, there was little to worry about.

[224][225][228] A small group of the Confederate cavalrymen, led by Captain James Breckinridge, who was killed, charged the advancing Union soldiers, giving Pickett enough time to pass using the horse's head and neck as a shield.

[231] After Mayo's brigade had been broken, Warren told Crawford to oblique his division to the right and occupy White Oak Road west of Five Forks to close the last line for Confederate retreat.

[233] Corse's men threw up light field works and Barringer's and Beale's brigades of Rooney Lee's cavalry division supported them to the south and west.

[232][233] Mackenzie's cavalry had advanced on the right of the V Corps and scattered Munford's picket line as well as screening the infantry from any attempt by Rosser's division north of Hatcher's Run to come in from behind.

[238] In his after action report, Pennington said the failure to maintain contact with Fitzhugh's brigade, the removal of Capehart's division from his left, and the fact that his men were running out of ammunition caused the retreat.

[198] After the Union cavalry broke the front line at the Five Forks intersection, Griffin's and Ayres's infantry divisions arrived at the scene, causing some disorder as units intermingled.

Some are similar to Earl J. Hess's numbers of about 600 killed and wounded, 4,500 prisoners and thirteen flags and six guns lost by the Confederates and 633 casualties for Warren's infantry and "probably...fewer" for Sheridan's cavalry.

[253] After some order was restored to the intermingled mass of survivors, Pickett moved the men in their re-formed units toward Exeter Mills at the mouth of Whippornock Creek where he planned to ford the Appomattox River and return to the Army of Northern Virginia.

[270] In the absence of available aides, Grant sent reporter Sylvanus Cadwallader of the New York Herald to bring the news of the victory at Five Forks along with captured battle flags to President Lincoln aboard the River Queen at City Point.

The Union Army soldiers Wilmon W. Blackmar, John Wallace Scott, Robert F. Shipley, Thomas J. Murphy, August Kauss, William Henry Harrison Benyaurd, Jacob Koogle, George J. Shopp, Joseph Stewart, William W. Winegar, Albert E. Fernald, Adelbert Everson, James G. Grindlay, Charles N. Gardner, Henry G. Bonebrake, Hiram H. De Lavie and David Edwards were all later awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the battle.