Battle of Ipsus

Hieronymus was a friend of Eumenes, and later became a member of the Antigonid court; he was therefore very much familiar and contemporary with the events he described, and possibly a direct eyewitness to some.

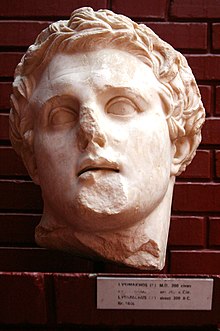

In the aftermath of the Second War of the Diadochi (315 BC), the aging satrap Antigonus I Monophthalmus had been left in undisputed control of the Asian territories of the Macedonian empire (Asia Minor, Syria and the vast eastern satrapies).

This war ended in a compromise peace in 311 BC, after which Antigonus attacked Seleucus, who was attempting to re-establish himself in the eastern Satrapies of the empire.

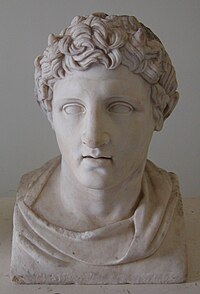

In the aftermath of this victory, Antigonus and Demetrius both assumed the crown of Macedon, in which they were shortly followed by Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and eventually Cassander.

Ptolemy took the title of Soter ("Savior") for his role in preventing the fall of Rhodes, but the victory was ultimately Demetrius's, as it left him with a free hand to attack Cassander in Greece.

Cassander therefore held counsel with Lysimachus, and they agreed on a joint strategy that included sending envoys to Ptolemy and Seleucus, asking them to join in combatting the Antigonid threat.

Seeking to take the initiative, Cassander sent a significant portion of the Macedonian army under Prepelaus to Lysimachus, which was to be used in joint operations in Asia Minor.

[7] When Antigonus received news of the invasion, he abandoned preparations for a great festival to be held in Antigonia, and quickly began to march his army northwards from Syria, through Cilicia, Cappadocia, Lycaonia, and into Phrygia.

[8] Lysimachus, hearing of the approach of Antigonus's army, held counsel with his officers, and decided to avoid open battle until Seleucus's arrival.

[8] Antigonus therefore moved to cut off the allies' provisions, forcing Lysimachus to abandon the camp and make a night-time march of some 40 miles to Dorylaion.

[9] With the siege works nearing completion and food running low, Lysimachus decided to abandon the camp, and marched away during a night-time storm.

[9] Whilst settling his army for the winter, Antigonus heard the news that Seleucus was en route from the eastern satrapies to support Lysimachus.

[11] He recaptured Ephesos, and marched north to the Hellespont, where he established a strong garrison and fleet to prevent European reinforcements reaching the allied army in Asia.

[12] Since Demetrius was guarding the easy crossing points at the Hellespont and the Bosphorus, Pleistarchus attempted to ship his men directly across the Black Sea to Heraclea, using the port of Odessos.

[12] Similarly, the concentration of Antigonid forces in Asia now made Ptolemy feel secure enough to bring an army out of Egypt to try to conquer Coele Syria.

[13] He captured a number of cities, but while laying siege to Sidon, he was brought false reports of an Antigonid victory, and told that Antigonus was marching south into Syria.

Lysimachus and Seleucus were probably anxious to bring Antigonus to battle, since their respective power-centres in Thrace and Babylon were vulnerable in their prolonged absence.

[15] The exact location of the battle is unknown, but it occurred in a large open plain, well-suited for both the allied preponderance of elephants and the Antigonid superiority in cavalry numbers and training.

[10] Based on other battles between the Diadochi, modern experts estimate that of the 70,000 Antigonid infantry, perhaps 40,000 were phalangites and 30,000 were light troops of various kinds.

[17] Diodorus claims that Seleucus brought 20,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry (including mounted archers), 480 elephants and more than a hundred scythed chariots with him from the eastern satrapies.

[20] In terms of overall strategy, it is clear that both sides had resolved on battle;[13] for the allies, it represented the best chance of stopping Antigonid expansion, rather than allowing themselves to be defeated piecemeal.

[17] However, little is known about the specific strategic considerations facing the two sides before the battle, as the precise circumstances and location of the engagement remain uncertain.

As mentioned above, it has been suggested that the allied army was trying to cut Antigonus's lines of communication with Syria, in order to prompt him into battle, but this is only one of several possible scenarios.

The use of novel weapons, such as war elephants and scythed chariots, to change the tactical balance was one approach used by the Diadochi, but such innovations were readily copied.

Thus, both sides at Ipsus had war elephants, although thanks to Seleucus, the allies were able to field an unusually high number, in addition to scythed chariots.

This move against the Antigonid right flank probably involved detaching cavalry from the allies own right wing, including Seleucus's horse-archers, who could rain down missiles on the immobile phalanx.

Despite the expectation that he would raid the Ephesian treasury, Demetrius instead immediately set sail for Greece "putting his chief remaining hopes in Athens".

As Paul K. Davis writes, "Ipsus was the high point of the struggle among Alexander the Great’s successors to create an international Hellenistic empire, which Antigonus failed to do.

Ipsus finalized the breakup of an empire, which may account for its obscurity; despite that, it was still a critical battle in classical history and decided the character of the Hellenistic age.