Battle of Jenkins' Ferry

Although the battle ended with a Union victory, the Confederates saw it as a strategic success as they claimed to have prevented Frederick Steele from holding southwest Arkansas.

Jenkins' Ferry was the decisive engagement of Steele's Camden Expedition (a part of the Red River Campaign) and E. Kirby Smith's last.

The campaign's immediate objective was the capture of Shreveport, Louisiana, which was the headquarters of General E. Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department.

[1] Henry Halleck, Major-General and General-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States, who devised the plan, also wanted to open the road to the occupation of Texas by U.S. forces and to discourage French incursions from Mexico.

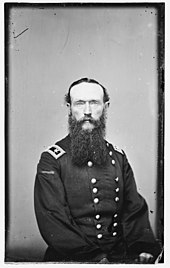

[6] Major-General Frederick Steele commanding approximately 14,000 men also was supposed to move his forces in support of Banks against Shreveport from their bases to the north at Little Rock, Fort Smith, and Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

Steele later said its objective was to reach and occupy Camden, Arkansas, and to draw Confederate cavalry away from Shreveport in support of Banks's effort to take that city.

Steele planned to meet a federal column of 4,000 men from Fort Smith, led by Brigadier-General John Thayer, at Arkadelphia.

[14] Price had earlier evacuated that fortified town in order to defend the temporary Confederate state capital at Washington, Arkansas.

[20] About the time the remnants of the federal force who were not killed or captured at Poison Spring stumbled back into Camden, Steele learned that General Banks had turned back in his drive toward Shreveport after being defeated at the Battle of Mansfield, Louisiana (also known as Pleasant Grove or Sabine Cross Roads), about 40 miles (64 km) from Shreveport, on April 8, 1864.

Porter had to return not only because of Banks's retreat but because his flotilla was in danger of being stranded by uncommonly low water levels in the Red River.

As Banks appeared to be waiting for the naval force at Alexandria, Louisiana, Kirby Smith became even more certain that his decision was correct and he had time to execute it.

[30] Meanwhile, on April 28, Price sent Samuel Maxey's division of two cavalry brigades back to Oklahoma and Texas to attend to reported threats to that territory by another federal force.

[31] Brigadier-General Fagan, who had commanded the victorious Confederate forces at Marks Mill, took off on independent operations but did not fulfill his orders, which permitted this movement along with some stated objectives.

Fagan also failed to occupy a position across Steele's supply and communication lines between Camden and Little Rock, as Price had ordered.

His force was harassed by Confederate cavalry as General Marmaduke's men caught up to the federal column on their approach to the Saline River.

Now Steele had to fight off Kirby Smith's army before his infantry forces could finish their efforts to get their wagons, artillery, and remaining troops over their pontoon bridge river crossing.

[36] Before dawn on April 30, 1864, Marmaduke's Confederate cavalry troopers arrived near Jenkins' Ferry, dismounted and skirmished with Steele's rear guard infantry force about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the Saline River crossing.

In turn, they each made little headway because they had no cover for an attack, and the approach to the Federal position was ankle to knee-deep in mud and pools of water.

[36] After Price's forces under Brigadier-Generals Churchill and Parsons had made little progress, Kirby Smith came up with the large Texas infantry division under Major-General John Walker.

[36] By about 3:00 p.m. on April 30, 1864, the Federal forces finally crossed the Saline River with all their remaining men and the artillery pieces and equipment and supply wagons which were not irretrievably stuck in the mud, which they burned.

This allowed the Federal forces time and space to move most of their remaining wagons, artillery, equipment, cavalry, and infantry across the Saline River and escape back to Little Rock's safety.

He also lost 635 wagons, 2,500 mules, enough horses to mount a cavalry brigade and a long list of captured material, including ammunition, food and medical supplies.

Kirby Smith's last hope to destroy Steele's army outside of his well-fortified base at Little Rock was dashed as a result of the mismanaged, disjointed, and piecemeal attacks at Jenkins' Ferry.

After the Federal left flank was closed off, any opportunity for a successful Confederate attack at that point and any realistic chance Kirby Smith and Price might have had to trap most of Steele's force was gone.

[39] After his situation had become hopeless at Camden, Steele gave up all thoughts of uniting with Banks on the Red River in a further campaign to take Shreveport and realized that he had to save his army.

His major problems in renewing the campaign actually did not include an insufficient number of men, however, because he was reinforced in late April by forces under Major-General John McClernand.

Banks had logistical problems and would not have gunboat transport and support because of Porter's inability to operate in the shallow water of the Red River during that spring and summer.

The Federals lost over 8,000 men in the Red River Campaign, including the Camden Expedition, and returned to their starting points at the end of it.

[49] The battlefield, preserved as Jenkins' Ferry Battleground State Park, is one of the Camden Expedition Sites that together were declared a National Historic Landmark in 1994.

[50] The battle is briefly depicted and mentioned by fictional soldiers Private Harold Green of the 116th United States Colored Infantry Regiment and Corporal Ira Clark of the 5th Massachusetts (Colored) Cavalry Regiment who speak with President Abraham Lincoln (played by Daniel Day-Lewis), in the opening scene of the 2012 Steven Spielberg film Lincoln.