Battle of Kadesh

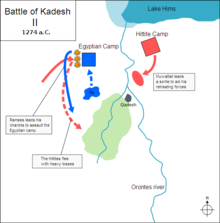

Their armies engaged each other at the Orontes River, just upstream of Lake Homs and near the archaeological site of Kadesh, along what is today the Lebanon–Syria border.

[14][15][16] After being outmaneuvered, ambushed, and surrounded, Ramesses II personally led a charge through the Hittite ranks with his bodyguard.

[17][18] After expelling the Hyksos' 15th Dynasty around 1550 BC, the rulers of the New Kingdom of Egypt became more aggressive in reclaiming control of their state's borders.

[citation needed] Many Egyptian accounts between c. 1400 and 1300 BCE reflect the general destabilization of Djahy, a region in southern Canaan.

During the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, Egypt continued to lose territory to the Mitanni in northern Syria.

[citation needed] During the late Eighteenth Dynasty, the Amarna letters tell the story of the decline of Egyptian influence in the region.

[19] Horemheb (d. 1292 BC), the last ruler of this dynasty, campaigned in this region, finally beginning to turn Egyptian interest back to the area.

Like his father Ramesses I, Seti I was a military commander who set out to restore Egypt's empire to the days of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaohs almost a century before.

He made an informal peace with the Hittites, took control of coastal areas along the Mediterranean Sea, and continued campaigning in Canaan.

In the fourth year of his reign, he marched north into Syria to recapture Amurru[22] or as a probing effort to confirm his vassals' loyalty and explore the terrain for possible battlegrounds.

[21] In the spring of the fifth year of his reign, in May 1274 BC, Ramesses II launched a campaign from his capital Pi-Ramesses (modern Qantir).

[24] There was also a poorly documented troop called the nrrn (Ne'arin or Nearin), who were possibly Canaanite military mercenaries[25] or Egyptians,[26] that Ramesses II had left in Amurru in order to secure the port of Sumur.

Healy in Armies of the Pharaohs observes: It is not possible to be precise about the size of the Egyptian chariot force at Kadesh though it could not have numbered less than 2,000 vehicles spread through the corps of Amun, P'Re, Ptah and Sutekh, assuming that approx.

To this we may need to add those of the Ne'arin, for if they were not native Egyptian troops their number may not have been formed from chariots detached from the army corps.

Ramesses II recorded a long list of 19 Hittite allies brought to Kadesh by Muwatalli.

[29]As Ramesses II and the Egyptian advance guard were about 11 kilometers from Kadesh, south of Shabtuna, he met two Shasu nomads who told him that the Hittite king was "in the land of Aleppo, on the north of Tunip" 200 kilometers away, where, the Shasu said, he was "(too much) afraid of Pharaoh, L.P.H., to come south".

[30] This was, according to Egyptian texts, a false report ordered by the Hittites "with the aim of preventing the army of His Majesty from drawing up to combat with the foe of Hatti".

The momentum of the Hittite attack began to wane as chariots were impeded by and in some cases crashing into obstacles in the large Egyptian camp.

[33] In the Egyptian account, Ramesses describes himself as being deserted and surrounded by enemies: "No officer was with me, no charioteer, no soldier of the army, no shield-bearer[.

[15] Having suffered this significant reversal in the battle, Muwatalli II still commanded a large force of reserve chariotry and infantry, as well as the walls of the town.

As the retreat reached the river, he ordered another thousand chariots to counter-attack, led by high nobles close to the king.

[37] The remaining Hittite elements were forced to abandon their chariots and attempt to swim the river "as fast as crocodiles" (according to Egyptian accounts).

[36] Unable to support a long siege of the walled city of Kadesh,[3] Ramesses gathered his troops and headed south towards Damascus and ultimately back to Egypt.

After moving into the ambush, facing defeat and death, the king had managed to rally his scattered troops and save the day.

It is held as a turning point for the Egyptians, who had developed new technologies and rearmed against years of territorial incursions by the Hittites.

The treaty was inscribed on a silver tablet, of which a clay copy was found in the Hittite capital Hattusa, now in Turkey, and is on display at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

A large replica hangs on a wall at the headquarters of the United Nations, as the earliest international peace treaty known to historians.

[50] Hittite references to the battle, including the above letter, have been found at Hattusa, but no annals have been discovered that might describe it as part of a campaign.

)", in Cambridge Ancient History (1975) p. 253; Gardiner, Alan, The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II (1975) pp. 57ff.