Battle of Legnano

[8][9] The battle was crucial in the long war waged by the Holy Roman Empire in an attempt to assert its power over the municipalities of northern Italy,[8] which decided to set aside their mutual rivalries and join in a military alliance symbolically led by Pope Alexander III, the Lombard League.

This resulted a few years later in the Peace of Constance (25 June 1183), with which the Emperor recognized the Lombard League and made administrative, political, and judicial concessions to the municipalities, officially ending his attempt to dominate northern Italy.

[11][12] The battle is alluded to in the Canto degli Italiani by Goffredo Mameli and Michele Novaro, which reads: «From the Alps to Sicily, Legnano is everywhere» in memory of the victory of Italian populations over foreign ones.

[19] When a city's bishop, who had traditionally exerted a strong influence on the civil matters of the municipality,[20] became largely preoccupied with the contest between Empire and Papacy, the citizens were stimulated, and in some ways obliged, to seek a form of self-government that could act independently in times of serious difficulty.

[21] The change that led to a collegial management of public administration was rooted in the Lombard domination of northern Italy;[22] this Germanic people was in fact accustomed to settling the most important questions (which were usually of military nature) through an assembly presided over by the king and composed of the most valiant soldiers, the "gairethinx"[23] or "arengo".

[8] Moreover, previous emperors, for various vicissitudes, adopted for a certain period an attitude of indifference towards the issues of northern Italy,[16] taking more care to establish relations that provided for supervision of the Italian situation rather than the effective exercise of power.

[25] As a consequence, imperial power did not prevent the expansionist aims of the various municipalities in the surrounding territories and other towns,[25] and cities began taking up arms against each other in contests to achieve regional hegemony.

[28] Of these, two contributed the most to fuel anti-imperial sentiment: to try to interrupt the supplies in Milan during one of his descents in Italy, in 1160, the emperor devastated the area north of the city destroying the crops and fruit trees of farmers.

[33][34] This campaign continued with the convocation of diet of Roncaglia, with which Frederick re-established imperial authority, nullifying, among other things, the conquests made by Milan in previous years, especially with regard to Como and Lodi.

[33] The first part of that journey continued along the Via Francigena[35] and ended in Rome with the coronation of Frederick Barbarossa as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Adrian IV (18 June 1155[36]).

[31][37][38] During his stay in Rome, Frederick, who had left from the north with the title of King of Germany, was harshly contested by the people of the city;[39] in response, the emperor reacted by stifling the revolt in blood.

[47] After receiving reinforcements from Germany and having conquered several riotous municipalities in northern Italy during a military campaign that lasted a few years, Barbarossa turned its attention to Milan, which was first besieged in 1162 and then, after its surrender (1 March[48]), completely destroyed.

[6][54] With pacific Lombardy,[55] Frederick in fact preferred to postpone the clash with the other municipalities of northern Italy due to the numerical scarcity of his troops and then, after having verified the situation, he returned to Germany.

[56] To avoid the Marca of Verona, after having crossed the Alps from the Brenner Pass, instead of going along the usual Adige Valley, Barbarossa turned towards Val Camonica;[56][57] its objective was not, however, the attack on the rebellious Italian communes, but the Papacy.

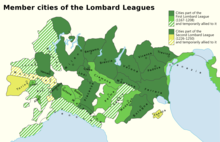

[60] A few months before the epidemic that struck the imperial army, the municipalities of northern Italy had joined forces in the Lombard League,[31] a military union whose Latin name was Societas Lombardiae.

[79] Realizing the mistake he made, which would later prove decisive, the emperor met his cousin Henry the Lion and other feudal lords in Chiavenna between January and February 1176 with the aim of asking for reinforcements to continue his campaign.

[91] On the night of 28-29 May 1176, during the descent towards Pavia, Frederick Barbarossa was with his troops at the monastery of the Benedictine nuns of Cairate[61] for a stop which later proved to be fatal, since it caused a delay compared to the contemporaneous moves of the Lombard League.

[92] Barbarossa decided to stop in Cairate to cross the River Olona, the only natural barrier that separated it from the faithful Pavia, trusting to have the possibility to enter the area controlled by the allied city after having traveled the remaining 50 km in a horse day.

[102] This choice turned out to be wrong: in fact Barbarossa arrived from Borsano (nowadays frazione (hamlet) of Busto Arsizio), that is from the opposite side, forcing the municipal troops to resist around the Carroccio with the escape road blocked by the Olona.

At the time the village represented an easy access for those coming from the north to the Milanese countryside, given that it was located at the mouth of the Valle Olona, which ends at Castellanza;[103] this passage had therefore to be closed and strenuously defended to prevent the attack on Milan, which was also facilitated by the presence of an important road that existed since Roman times, the Via Severiana Augusta, which connected Mediolanum (the modern Milan) with the Verbanus Lacus (Lake Verbano, or Lake Maggiore[105]), and from there to the Simplon Pass (lat.

The Cotta castle was flanked by a defensive system formed by walls and a flooded moat that encircled the inhabited center, and by two access gates to the village: medieval Legnano thus appeared as a fortified citadel.

[118] During the fight, which lasted eight to nine hours from morning to three in the afternoon[119] and which was characterized by repeated charges punctuated by long pauses to make the armies repackage and refurbish,[120] the first two lines finally gave way, but the third resisted shocks.

[123][124] The waters of the river were the theater of the last phases of the battle, which ended with the capture and killing of many soldiers of the imperial army[100][122] and with the sacking of the military camp of Frederick Barbarossa in Legnano.

[6][122] After the battle, the Milanese wrote to the Bolognese, their allies in the League, a letter stating, among other things, that they had in custody, right in Milan, a conspicuous loot in gold and silver, the banner, the shield and the imperial spear, and a large number of prisoners, including Count Berthold I of Zähringen (one of the princes of the Empire), Philip of Alsace (one of the empress's grandchildren) and Gosvino of Heinsberg (the brother of the Archbishop of Cologne).

[6] The position of the lances within this formation, all facing outwards, was certainly another reason for the victorious resistance, given that it constituted a defensive bulwark that could not be easily overcome[6] Furthermore, the municipal troops, grouped on a territorial basis, were linked by kinship or neighborhood relations, which contributed to further compacting the ranks.

[138] The most important contemporary ecclesiastical sources are the writings of the Archbishop of Salerno and the Life of Alexander III drafted by Boso Breakspeare,[138] with the first not referring to the indication of the places,[142] and the second that report the crippled toponym of Barranum.

[158][11] Frederick also lost the military support of the German princes,[159] who, after the 10,000 knights provided at the beginning of his campaign and the 3,000 laboriously collected shortly before the battle of Legnano, would hardly have given Barbarossa more aid to resolve the situation in Italy, which would have brought them very little benefit.

[46][168] As far as legal proceedings were concerned, the imperial vicars would have intervened in disputes only for the appeal cases that involved goods or compensation worth more than 25 lire, but applying the laws in force in the individual municipalities.

[172] The name of Alberto da Giussano appeared for the first time in the historical chronicle of the city of Milan written by the Dominican friar Galvano Fiamma in the first half of the 14th century, that is 150 years after the battle of Legnano.

[174] According to Galvano Fiamma, the Company of Death defended the Carroccio[175] to the extreme and then carried out, in the final stages of the battle of Legnano, a charge against the imperial army of Frederick Barbarossa.