Giuseppe Garibaldi

However, breaking with Mazzini, he pragmatically allied himself with the monarchist Cavour and Kingdom of Sardinia in the struggle for independence, subordinating his republican ideals to his nationalist ones until Italy was unified.

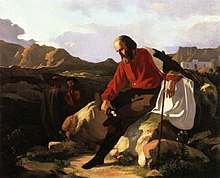

After participating in an uprising in Piedmont, he was sentenced to death, but escaped and sailed to South America, where he spent 14 years in exile, during which he took part in several wars and learned the art of guerrilla warfare.

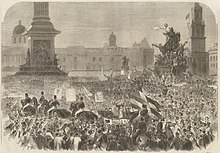

[5][6] He was showered with admiration and praise by many contemporary intellectuals and political figures, including Abraham Lincoln,[7] William Brown,[8] Francesco de Sanctis, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Malwida von Meysenbug, George Sand, Charles Dickens,[9] and Friedrich Engels.

During ten days in port, he met Giovanni Battista Cuneo from Oneglia, a politically active immigrant and member of the secret Young Italy movement of Giuseppe Mazzini.

When the rebels proclaimed the Catarinense Republic in the Brazilian province of Santa Catarina in 1839, she joined him aboard his ship, Rio Pardo, and fought alongside him at the battles of Imbituba and Laguna.

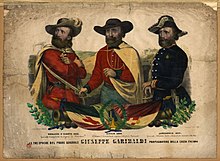

Though contemporary sources do not mention the Redshirts, popular history asserts that the legion first wore them in Uruguay, getting them from a factory in Montevideo that had intended to export them to the slaughterhouses of Argentina.

When news of these reforms reached Montevideo, Garibaldi wrote to the Pope: If these hands, used to fighting, would be acceptable to His Holiness, we most thankfully dedicate them to the service of him who deserves so well of the Church and of the fatherland.

After the crushing Piedmontese defeat at the Battle of Novara on 23 March 1849, Garibaldi moved to Rome to support the Roman Republic recently proclaimed in the Papal States.

Garibaldi, having entered the chamber covered in blood, made a speech favouring the third option, ending with: Ovunque noi saremo, sarà Roma[26] ("Wherever we will go, that will be Rome").

The sides negotiated a truce on 1–2 July, Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops, and ceded his ambition to rouse popular rebellion against the Austrians in central Italy.

He attended the Masonic lodges of New York in 1850, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism, whose minds were open to socialist thought, and to giving Freemasonry a strong anti-papal stance.

A local Italian merchant, Pietro Denegri, gave him command of his ship Carmen for a trading voyage across the Pacific, for which he required Peruvian citizenship, which he obtained that year.

Garibaldi, already a popular figure on Tyneside, was welcomed enthusiastically by local working men—although the Newcastle Courant reported that he refused an invitation to dine with dignitaries in the city.

The young Henry Adams—later to become a distinguished American writer—visited the city in June and described the situation, along with his meeting with Garibaldi, in a long and vivid letter to his older brother Charles.

[48] Garibaldi expressed interest in aiding the Union, and he was offered a major general's commission in the U.S. Army through a letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to Henry Shelton Sanford, the U.S. Minister at Brussels, 27 July 1861.

[7] On 9 September 1861, Sanford met with Garibaldi and reported the result of the meeting to Seward: He said that the only way in which he could render service, as he ardently desired to do, to the cause of the United States, was as Commander-in-chief of its forces, that he would only go as such, and with the additional contingent power—to be governed by events—of declaring the abolition of slavery—that he would be of little use without the first, and without the second it would appear like a civil war in which the world at large could have little interest or sympathy.

[50] A historian of the American Civil War, Don H. Doyle, however, wrote, "Garibaldi's full-throated endorsement of the Union cause roused popular support just as news of the Emancipation Proclamation broke in Europe.

A government steamer took him to a prison at Varignano near La Spezia, where he was held in a sort of honourable imprisonment and underwent a tedious and painful operation to heal his wound.

Following the wartime collapse of the Second French Empire after the Battle of Sedan, Garibaldi, undaunted by the recent hostility shown to him by the men of Napoleon III, switched his support to the newly declared Government of National Defense of France.

[65] Garibaldi suggested a grand alliance between various factions of the left: "Why don't we pull together in one organized group the Freemasonry, democratic societies, workers' clubs, Rationalists, Mutual Aid, etc., which have the same tendency towards good?".

[65] The Congress was held in the Teatro Argentina despite being banned by the government, and endorsed a set of radical policies including universal suffrage, progressive taxation, compulsory lay education, administrative reform, and abolition of the death penalty.

[65] Garibaldi had long claimed an interest in vague ethical socialism such as that advanced by Henri Saint-Simon and saw the struggle for liberty as an international affair, one which "does not make any distinction between the African and the American, the European and the Asian, and therefore proclaims the fraternity of all men whatever nation they belong to".

Although he did not agree with their calls for the abolition of property, Garibaldi defended the Communards and the First International against the attacks of their enemies: "Is it not the product of the abnormal state in which society finds itself in the world?

"[72] In describing the move to the left of Garibaldi and the Mazzinians, Lucy Riall writes that this "emphasis by younger radicals on the 'social question' was paralleled by an increase in what was called 'internationalist' or socialist activity (mostly Bakuninist anarchism) throughout northern and southern Italy, which was given a big boost by the Paris Commune".

He came out entirely in favour of the Paris Commune and internationalism, and his stance brought him much closer to the younger radicals, especially Felice Cavallotti, and gave him a new lease on political life.

In 1879, Garibaldi founded the League of Democracy, along with Cavallotti, Alberto Mario and Agostino Bertani, which reiterated his support for universal suffrage, abolition of ecclesiastical property, the legal and political emancipation of women and a plan of public works to improve the Roman countryside that was completed.

The books were also notable for their vivid evocation of landscape (Trevelyan had himself followed the course of Garibaldi's marches), for their innovative use of documentary and oral sources, and for their spirited accounts of battles and military campaigns.

We need the kind of leadership which, in the true tradition of medieval chivalry, would devote itself to redressing wrongs, supporting the weak, sacrificing momentary gains and material advantage for the much finer and more satisfying achievement of relieving the suffering of our fellow men.

[95] Several places worldwide are named after him, including: Garibaldi is a major character in two juvenile historical novels by Geoffrey Trease: Follow My Black Plume and A Thousand for Sicily.

On 18 February 1960, the American television series Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre aired the episode "Guns for Garibaldi" to commemorate the centennial of the unification of Italy.