Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

1776 1777 1778 1779 The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a minor conflict of the American Revolutionary War fought near Wilmington (present-day Pender County), North Carolina, on February 27, 1776.

The victory of the North Carolina Provincial Congress' militia force over British governor Josiah Martin's and Tristan Worsley's reinforcements at Moore's was a turning point in the war; American independence was declared less than five months later.

Revolutionary militia and Continental units mobilized to prevent the junction, blockading several routes until the poorly armed loyalists were forced to confront them at Moore's Creek Bridge, about 18 miles (29 km) north of Wilmington.

North Carolina was not militarily threatened again until 1780, and memories of the battle and its aftermath negated efforts by Charles Cornwallis to recruit loyalists in the area in 1781.

[4] In early 1775, with political and military tensions rising in the Thirteen Colonies, North Carolina's royal governor, Josiah Martin, hoped to combine the recruiting of Scots Gaels in the North Carolina interior with that of sympathetic former Regulators (a group originally opposed to corrupt colonial administration) and disaffected loyalists in the coastal areas to build a large loyalist force to counteract patriot sympathies in the province.

[6] At about the same time, Scotsman Allan Maclean successfully lobbied King George III for permission to recruit Loyalist Scots throughout North America.

[9] On January 3, 1776, Martin learned that an expedition of more than 2,000 troops under the command of General Henry Clinton was planned for the southern colonies and that their arrival was expected in mid-February.

[12] Meanwhile, word of the Cross Creek muster reached the Patriots of the North Carolina Provincial Congress just a few days after it happened.

Local committees of safety in Wilmington and New Bern also had active militia units led by Alexander Lillington and Richard Caswell, respectively.

General MacDonald learned of their arrival and sent Colonel Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on all Patriots to lay down their arms.

[15] In a council held that night, the loyalists decided to attack since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area.

[17] Furthermore, the marching had taken its toll on the elderly Brigadier General MacDonald; he fell ill and turned over command to Lieutenant Colonel Donald MacLeod.

MacLeod ordered his men to adopt a defensive line behind nearby trees, but then a Patriot sentry across the river fired his musket to warn Caswell of the loyalist arrival.

In response to a Patriot call for identification shouted from across the creek, Captain Alexander Mclean identified himself as a friend of the King.

He stated in his report that 30 loyalists were killed or wounded, "but as numbers of them must have fallen into the creek, besides more that were carried off, I suppose their loss may be estimated at fifty.

[20][21] Combined with the capture of the loyalist camp at Cross Creek, the patriots confiscated 1,500 muskets, 300 rifles, and $15,000 (as valued at the time) of Spanish gold.

[19] The battle had significant effects on the Scottish Gaels of North Carolina, where loyalist sympathizers refused to take up arms whenever recruitment efforts were made later in the war, and those who did were routed out of their homes by the pillaging activities of their patriot neighbors.

[25] The Moore's Creek Bridge battlefield site was preserved in the late 19th century through private efforts that eventually received state financial support.

[28] Early accounts of the battle often misstated the size of both forces involved, typically reporting that 1,600 loyalists faced 1,000 patriots.

The following units participated in this battle:[30] Minutemen and State Troops: Local Militia: Historian David Wilson, however, points out that the large loyalist size is attributed to reports by General MacDonald and Colonel Caswell.

MacDonald gave that figure to Caswell, representing a reasonable estimate of the number of men starting the march at Cross Creek.

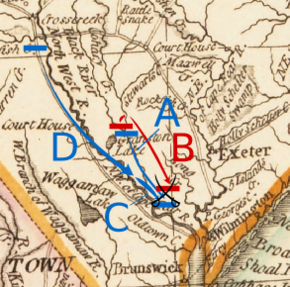

A: Moore moves from Wilmington to Rockfish Creek

B: MacDonald moves to Corbett's Ferry

C: Caswell moves from New Bern to Corbett's Ferry

A: Caswell's movement

B: MacDonald's movement

C: Lillington and Ashe's movement

D: Moore's movement