Battle of Nanking

[18] On November 7 its de facto leader Deputy Chief of Staff Hayao Tada laid down an "operation restriction line" preventing its forces from leaving the vicinity of Shanghai, or more specifically from going west of the Chinese cities of Suzhou and Jiaxing.

[17] In fact, Matsui was highly sympathetic with Yanagawa's actions[23] and a few days later on November 22 Matsui issued an urgent telegram to the Army General Staff insisting that "To resolve this crisis in a prompt manner we need to take advantage of the enemy's present declining fortunes and conquer Nanking ... By staying behind the operation restriction line at this point we are not only letting our chance to advance slip by, but it is also having the effect of encouraging the enemy to replenish their fighting strength and recover their fighting spirit and there is a risk that it will become harder to completely break their will to make war.

[20] On November 15, near the end of the Battle of Shanghai, Chiang Kai-shek convened a meeting of the Military Affairs Commission's Supreme National Defense Council to undertake strategic planning, including a decision on what to do in case of a Japanese attack on Nanjing.

[27] Following the Manchurian Incident of 1931, the Chinese government began a fast track national defense program with massive construction of primary and auxiliary air force bases around the capital of Nanjing including Jurong Airbase, completed in 1934, from which to facilitate aerial defense as well as launching counter-strikes against enemy incursions; on August 15, 1937, the IJN launched the first of many heavy schnellbomber (fast bomber) raids against Jurong Airbase using the advanced G3Ms based upon Giulio Douhet's blitz-attack concept in an attempt to neutralize the Chinese Air Force fighters guarding the capital city, but was severely repulsed by the unexpected heavy resistance and performance of the Chinese fighter pilots stationed at Jurong, and suffering almost 50% loss rate.

As a result, the Chinese infantry were slowly pushed back, and finally broke into a retreat towards Guangde when Japanese troops flanked their positions on the lake's shores via stolen civilian motor boats.

[80] The hills around Jiangyin were the site of vicious fighting, with Mount Ding changing hands several times, resulting in Chinese company commander Xia Min'an being killed in action.

[101] On December 5, Chiang Kai-shek paid a visit to a defensive encampment near Jurong to boost the morale of his men but was forced to leave when the Imperial Japanese Army began their attack on the battlefield.

[102] On that day the rapidly moving forward contingents of the SEA occupied Jurong and then arrived near Chunhua(zhen), a town 15 miles southeast of Nanjing and a key point of the capital's outer line of defense which would put Japanese artillery in range of the city.

Despite facing difficulties in using the fortifications around the town due to a lack of keys, the 51st Division had managed to establish a three-line defense with pillboxes, hidden machine gun nests, two rows of barbed wire and an anti-tank ditch.

[120] The American journalist F. Tillman Durdin, who was reporting on site during the battle, saw one small group of Chinese soldiers set up a barricade, assemble in a solemn semicircle, and promise each other that they would die together where they stood.

The 6th division's progress was slow and casualties were heavy, as Yuhuatai was built like a fortress of interlocking fortifications and trenches, fortified with dense tangles of barbed wire, antitank ditches and concrete pillboxes.

[125] The Japanese attacked the 88th division on December 10, but suffered heavy casualties, as they had to fight through hilly terrain covered in barbed wire barricades and tactically placed machine gun nests.

[128] The Japanese made an attempt to infiltrate a "suicide squadron" bearing explosive picric acid up to the Zhonghua Gate to blow a hole in it, but it got lost in the morning fog and failed to reach the wall.

[132] After some deliberation through the night, the 87th Division, having already suffered 3,000 casualties, abandoned their positions on the Gate of Enlightenment at 2am on December 13 to retreat to the Xiaguan wharfs, leaving some 400 of the most severely wounded who could not walk behind in the city.

[135] At the height of the battle, Tang Shengzhi complained to Chiang that, "Our casualties are naturally heavy and we are fighting against metal with merely flesh and blood",[136] but what the Chinese lacked in equipment they made up for in the sheer ferocity with which they fought, partially due to strict orders that no man or unit was to retreat one step without permission.

[139] The Panay was about twenty-eight miles upstream from Nanjing when Japanese naval aircraft led by Lt. Shigeharu Murata (who would later lead torpedo bomber squadrons against Pearl Harbor) attacked and bombed the gunboat.

[141] The crew and passengers hid in the reeds of a nearby island, and witnessed a passing Japanese motorboat machine-gun the sinking ship and board it briefly before departing; the American flag had still been flying from the bow at that time.

[140] An Imperial Army officer in the vicinity, Col. Kingoro Hashimoto, a founder of one of the right-wing secret societies in Japan, also ordered firing on the Panay as it was sinking, in additional to several British vessels whose identities he knew, including the SS Scarab and HMS Cricket.

[135] On December 12 the 16th division captured the second peak of Zijinshan, and from this vantage point unleashed a torrent of artillery fire at Zhongshan Gate where a large portion of the wall suddenly gave way.

[146] Tang prepared to do so the next day on December 12, but startled by Japan's intensified onslaught he made a frantic last-minute bid to conclude a temporary ceasefire with the Japanese through German citizens John Rabe and Eduard Sperling.

Having obtained some 20 private vessels ahead of time, the 2nd Army managed to evacuate 11,851 officers and soldiers, save for the 5,078 casualties already lost in battle, across the Yangtze River just before Japanese naval units blockaded the way.

However, only half of the gate was open, and combined with the crowd's density and disorganized movements, a deadly bottleneck formed that resulted in hundreds of people being crushed or trampled to death, including Colonel Xie Chengrui of the Training Division.

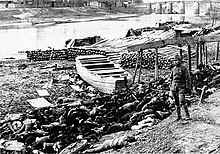

[168][24] By the afternoon of December 13, the Japanese had virtually completed their encirclement of Nanjing, and patrols and sailors on naval vessels began shooting at soldiers and civilians crossing the Yangtze from both sides of the river.

[171] However, the criteria used were often arbitrary as was the case with one Japanese company which apprehended all men with "shoe sores, callouses on the face, extremely good posture, and/or sharp-looking eyes" and for this reason many civilians were taken at the same time.

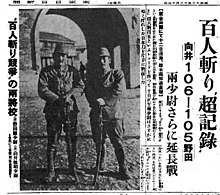

The International Military Tribunal in Tokyo, using the thorough records of the Safety Zone Committee, found that some 20,000 male civilians were killed on false grounds of being soldiers, whilst another 30,000 genuine former combatants were unlawfully executed and their bodies disposed of in the river.

According to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, the total number of civilians and prisoners of war murdered in Nanjing and its vicinity during the first six weeks of the Japanese occupation was over 200,000 while at least 20,000 women were raped, including infants and the elderly.

"[37] An official report of the Nationalist Government argued that an excess of untrained and inexperienced troops was a major cause of the defeat, but at the time Tang Shengzhi was made to bear much of the blame and later historians have also criticized him.

[136][205] Japanese historian Tokushi Kasahara, for instance, has characterized his battlefield leadership as incompetent, arguing that an orderly withdrawal from Nanjing may have been possible if Tang had carried it out on December 11 or if he had not fled his post well in advance of most of his beleaguered units.

Masahiro Yamamoto believes that Chiang chose "almost entirely out of emotion" to fight a battle he knew he could only lose,[208] and fellow historian Frederick Fu Liu concurs that the decision is often regarded as one of "the greatest strategical mistakes of the Sino-Japanese war".

[204] Even so, buoyed by their victory, the Japanese government replaced the lenient terms for peace which they had relayed to the mediator Ambassador Trautmann prior to the battle with an extremely harsh set of demands that were ultimately rejected by China.