Battle of North Anna

The Battle of North Anna was fought May 23–26, 1864, as part of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

After disengaging from the stalemate at Spotsylvania Court House, Grant moved his army to the southeast, hoping to lure Lee into battle on open ground.

The II Corps under Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock stormed a small Confederate force at "Henagan's Redoubt" to seize the Chesterfield Bridge crossing on the Telegraph Road but did not advance further south across the river.

Gen. James H. Ledlie was repulsed from an ill-conceived assault against a strong position at Ox Ford, the apex of the V. Unfortunately for the Confederates, Lee was disabled with heart issues, and none of his subordinates were able to execute his planned attack.

After two days of skirmishing in which the armies stared at each other from their earthworks, the inconclusive battle ended when Grant ordered another wide movement to the southeast, toward the crossroads at Cold Harbor.

President Abraham Lincoln had long advocated this strategy for his generals, recognizing that the city would certainly fall after the loss of its principal defensive army.

Sheridan's men mortally wounded Stuart in the tactically inconclusive Battle of Yellow Tavern (May 11) and then continued their raid toward Richmond, leaving Grant and Meade without the "eyes and ears" of their cavalry.

Gouverneur K. Warren and John Sedgwick unsuccessfully attempted to dislodge the Confederates under Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson from Laurel Hill, a position that was blocking them from Spotsylvania Court House.

On May 10, Grant ordered attacks across the Confederate line of earthworks, which by now extended over 4 miles (6.5 km), including a prominent salient known as the Mule Shoe.

Attacks by Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright on the western edge of the Mule Shoe, which became known as the "Bloody Angle," involved almost 24 hours of desperate hand-to-hand fighting, some of the most intense of the Civil War.

[11] Grant repositioned his lines in another attempt to engage Lee under more favorable conditions and launched a final attack by Hancock on May 18, which made no progress.

By dawn on May 21 they reached Guinea Station,[17] where a number of the Union soldiers visited the Chandler house, the site of Stonewall Jackson's death a year earlier.

The Union cavalry, riding out ahead, encountered 500 soldiers from Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett's division, which was marching north from Richmond to join Lee's army.

By this time, Lee had a clear picture of Grant's plan and he ordered Ewell to march south on the Telegraph Road, followed by Anderson's Corps, and A.P.

That night, Warren's V Corps bivouacked a mile east of the Telegraph Road and somehow managed to miss Lee's army marching south right next to it.

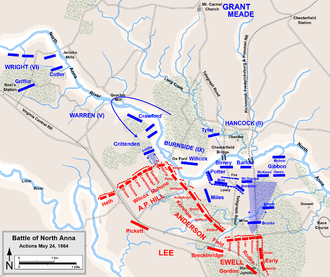

The corps commanders decided that Hancock would continue along the Telegraph Road to Chesterfield Bridge while Warren would cross the North Anna upstream at Jericho Mills.

Hearing from a prisoner that Confederates were camped nearby at the Virginia Central Railroad, Warren arranged his men into battle lines: the division of Brig.

Warren's V Corps was rescued from a significant defeat by his artillery, commanded by Col. Charles S. Wainwright, which placed 12 guns on a ridge and subjected the Confederates to plunging fire.

By moving south of the river, Lee hoped that Grant would assume that he was retreating, leaving only a token force to prevent a crossing at Ox Ford.

At 8 a.m., Hancock's II Corps finally crossed the Chesterfield Bridge, with the 20th Indiana and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters dashing across to disperse a thin Confederate picket line.

Downriver, the Confederates had burned the railway trestle, but soldiers from the 8th Ohio cut down a large tree and the men crossed on it single file.

Mark Grimsley has observed that the source of this view was Lee's aide-de-camp, Lt. Col. Charles S. Venable, who gave a speech about it in Richmond in 1873, which included the "we must strike them a blow" quotation.

Grimsley notes that "no surviving contemporaneous correspondence alludes to such an operation, and the troop movements made on the night of May 23 and on May 24 were limited and defensive in nature."

Col. Vincent J. Esposito of the United States Military Academy wrote that the success of any Confederate assault was not assured because Hancock's men were well dug in.

Wright's VI Corps attempted to flank the Confederate line by crossing Little River, but found that Wade Hampton's cavalry was covering the fords.

[37]As he did after the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, Grant now planned another wide swing around Lee's flank, marching east of the Pamunkey River to screen his movements from the Confederates.

He ordered (on May 22) that his supply depots at Belle Plain, Aquia Landing, and Fredericksburg be moved to a new base at Port Royal, Virginia, on the Rappahannock River.

Gen. James H. Wilson's cavalry division to cross the North Anna and move west, attempting to deceive Lee into thinking that the Union army intended to envelop the Confederate left flank.

They marched east on May 27 toward the crossings over the Pamunkey River at Hanovertown, while Burnside and Hancock remained in place to guard the fords on the North Anna.

[39] In 2011, the Board of Supervisors approved a conditional use permit allowing expansion of the rock quarry (now operated by Martin Marietta Materials Inc. and American Aggregates Corporation).