Battle of Perryville

When more Confederate divisions joined the fray, the Union line made a stubborn stand, counterattacked, but finally fell back with some units routed.

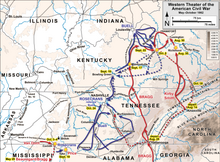

Beauregard retreated down into Corinth, very slowly pursued by the combined Union forces under Maj. Gen Henry Halleck – the armies of Grant, Buell, and John Pope.

Although Halleck had 100,000 men under his command and Beauregard half or less of that number, it took him 51 days to march the 20 miles from Pittsburg Landing to Corinth, which was abandoned by the Confederates on May 29.

In July 1862 Col. John Hunt Morgan carried out a successful cavalry raid in the state, venturing deeply into the rear areas of Buell's department.

Although Bragg was the senior general in the theater, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had established Kirby Smith's Department of East Tennessee as an independent command, reporting directly to Richmond.

Several captured letters from Confederate soldiers boasted that the Yankees would be given the slip (Maj. Gen William Rosecrans was impressed with Sheridan's foray and recommended him for promotion to brigadier general).

[18] On August 9, Smith informed Bragg that he was breaking the agreement and intended to bypass Cumberland Gap, leaving a small holding force to neutralize the Union garrison, and to move north.

He had to decide whether to continue toward a fight with Buell (over Louisville) or rejoin Smith, who had gained control of the center of the state by capturing Richmond and Lexington, and threatened to move on Cincinnati.

[27] The heat was oppressive for both men and horses, and the few sources of drinking water provided by the rivers and creeks west of town—most reduced to isolated stagnant puddles—were desperately sought after.

The 55,000 troops—many of whom Thomas described as "yet undisciplined, unprovided with suitable artillery, and in every way unfit for active operations against a disciplined foe"[33]—advanced toward Bragg's veteran army in Bardstown on three separate roads.

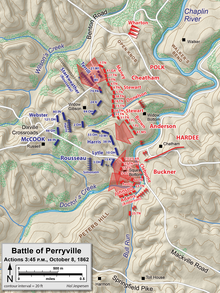

He wanted Polk to attack and defeat what he considered to be a minor force at Perryville and then immediately return so that the entire army could be joined with Kirby Smith's.

Polk sent a dispatch to Bragg early that morning that he intended to attack vigorously, but he quickly changed his mind and settled on a defensive posture.

Cheatham's division marched north from town and prepared to open the attack on the Union left—which Bragg assumed to be on the Mackville Road—beginning a large "left wheel" movement.

The large clouds of dust raised by Cheatham's division marching north at the double-quick prompted some of McCook's men to believe the Confederates were starting to retreat, which increased the surprise of the Rebel attack later in the day.

Gen. George E. Maney forward to deal with Parsons on the Open Knob, but Donelson's brigade could not withstand the fire and withdrew to its starting point at 2:30 p.m. with about 20% casualties; Savage's regiment lost 219 of its 370 men.

Meanwhile, Confederate Brigadier General George Maney's brigade was able to approach the Knob undetected through the woods, as the Union troops' attention was focused on Donelson's attack.

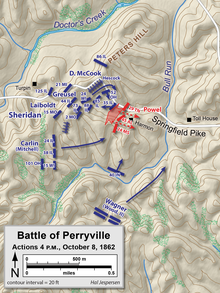

[47] Maney's attack continued to the west, down the reverse slope of the Open Knob, through a cornfield, and across the Benton Road, after which was another steep ridge, occupied by the 2,200 men in the Union 28th Brigade of Col. John C. Starkweather (Rousseau's division), and twelve guns.

Historian Kenneth W. Noe describes Maney's final repulse as the "high-water mark of the Confederacy in the western theater, no less important than the Angle at Gettysburg.

As they entered the valley, his men were cut down by musketry and fire from twelve artillery pieces on the next ridge, where the Union 9th Brigade (Rousseau's division) under Col. Leonard A. Harris was posted.

The corps' right flank, Col. William H. Lytle's 17th Brigade, was posted on a ridge on which Squire Bottom's house and barn were situated, overlooking a bend in the Chaplin River and a hill and farm owned by R. F. Chatham on the other side.

Gen. Bushrod R. Johnson's brigade descending from Chatham House Hill at about 2:45 p.m., crossing the almost-dry riverbed and attacking the 3rd Ohio Infantry, commanded by Col. John Beatty.

The attack was disorganized; last-minute changes of orders from Buckner were not distributed to all of the participating units and friendly fire from Confederate artillery broke their lines while still on Chatham House Hill.

[56] What soldier under Buell will forget the horrible affair at Perryville, where 30,000 men stood idly by to see and hear the needless slaughter in McCook's unaided, neglected and even abandoned command, without firing a shot or moving a step in its relief?

[60] Sheridan, who would be characterized in later battles as very aggressive, hesitated to pursue the smaller force, and also refused a request by Daniel McCook to move north in support of his brother's corps.

At times, we were so close that I was once able to give a Rebel a kick in the rear.Bragg's attack had been a large pincer movement, forcing both flanks of McCook's corps back into a concentrated mass.

The arrival of McCook's staff officer at about 4 p.m. surprised the army commander, who had heard little battle noise and found it difficult to believe that a major Confederate attack had been under way for some time.

When he had escaped he shouted to Liddell and the Confederates fired hundreds of muskets in a single volley, which killed Col. Squire Keith and caused casualties of 65% in the 22nd Indiana, the highest percentage of any Federal regiment engaged at Perryville.

At 9 p.m. he met with his subordinates at the Crawford House and gave orders to begin a withdrawal after midnight, leaving a picket line in place while his army joined up with Kirby Smith's.

Bragg was quickly called to the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia, to explain to Jefferson Davis the charges brought by his officers about how he had conducted his campaign, who were demanding that he be replaced as head of the army.

Historian James M. McPherson considers Perryville to be part of a great turning point of the war, "when battles at Antietam and Perryville threw back Confederate invasions, forestalled European mediation and recognition of the Confederacy, perhaps prevented a Democratic victory in the northern elections of 1862 that might have inhibited the government's ability to carry on the war, and set the stage for the Emancipation Proclamation which enlarged the scope and purpose of the conflict.