Battle of Philippi

The Second Triumvirate declared the civil war ostensibly to avenge Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, but the underlying cause was a long-brewing conflict between the Optimates and the Populares.

[citation needed] The battle, involving up to 200,000 men in one of the largest of the Roman civil wars, consisted of two engagements in the plain west of the ancient city of Philippi.

The Roman armies fought poorly, with low discipline, nonexistent tactical coordination and amateurish lack of command experience evident in abundance with neither side able to exploit opportunities as they developed.

In Rome the three main Caesarian leaders (Antony, Octavian and Lepidus), who controlled almost all the Roman army in the west, had crushed the opposition of the Senate and established the Second Triumvirate.

Although Antony and Octavian had been able to cross the sea with their main force, further communications with Italy were made difficult by the arrival of the Republican admiral Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, with a large fleet of 130 ships.

The Liberators did not wish to engage in a decisive battle, but rather to attain a good defensive position and then use their naval superiority to block the triumvirs' communications with their supply base in Italy.

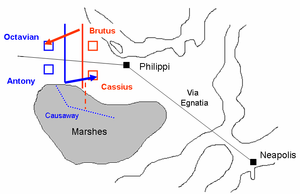

This meant that Brutus and Cassius could position their forces to hold the high ground along both sides of the Via Egnatia, about 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) west of the city of Philippi.

[9] This manoeuvre was finally noticed by Cassius, who countered by moving part of his army south into the marshes and constructing a transverse wall in a bid to cut off Antony's outstretched right wing.

[6] This surprise assault had complete success: Octavian's troops were put to flight and pursued up to their camp, which was captured by Brutus's men, led by Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus.

The battlefield was very large and clouds of dust made it impossible to make a clear assessment of the outcome of the battle, so both wings were ignorant of each other's fate.

On the same day as the first battle, the Republican fleet was able to intercept and destroy the triumvirs' reinforcements of two legions and other troops and supplies led by Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus.

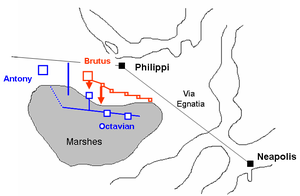

To avoid being outflanked, Brutus was compelled to extend his line to the south and then the east, parallel to the Via Egnatia, building several fortified posts.

While still holding the high ground he wanted to keep to the original plan of avoiding an open engagement and waiting for his naval superiority to wear out the enemy.

The traditional understanding is that Brutus, against his better judgment, subsequently abandoned this strategy because his officers and soldiers were tired of the delaying tactics and demanded he offer another open battle.

If the triumvirs were allowed to continue stretching their lines unimpeded to the east they would ultimately cut off his supply route to Neapolis and pin him against the mountains.

If that happened, the tables would be turned; Brutus would either be starved into submission or be forced to retreat by taking his entire army via the hazardous northern trail that had brought him to Philippi.

Ranged weapons such as arrows or javelins were largely ignored; instead, the soldiers packed into solid ranks and fought face-to-face with their swords, and the slaughter was terrible.

According to Cassius Dio, the two sides had little need for missile weapons, "for they did not resort to the usual manoeuvres and tactics of battles" but immediately advanced to close combat, "seeking to break each other's ranks".

In the account of Plutarch, Brutus had the better of the fight at the western end of his line and pressed hard on the triumvirs' left wing, which gave way and retreated, being harassed by the Republican cavalry, which sought to exploit the advantage when it saw the enemy in disorder.

"[7] Brutus's legions were driven back step-by-step, slowly at first, but as their ranks crumbled under the pressure they began to give ground more rapidly.

[7] The total casualties for the second battle of Philippi were not reported, but the close quarters fighting likely resulted in heavy losses for both sides.

[7] Although they had not been close friends, he remembered that Brutus had stipulated, as a condition for his joining the plot to assassinate Caesar, that the life of Antony be spared.

Antony remained in the East, while Octavian returned to Italy, with the difficult task of finding enough land on which to settle a large number of veterans.

[7] The Battle of Philippi marked the highest point of Antony's career: at that time he was the most famous Roman general and the senior partner of the Second Triumvirate.

Qui parentem meum [interfecer]un[t eo]s in exilium expuli iudiciis legitimis ultus eorum [fa]cin[us, e]t postea bellum inferentis rei publicae vici b[is a]cie. Res Gestae 2.