Battle of Pusan Perimeter logistics

Suffering mounting losses, the North Korean force on the west flank withdrew for several days to re-equip and receive reinforcements.

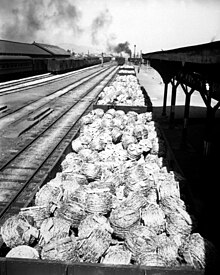

[21] The equipment and ordnance supplies that was available to the United States forces in Korea in the first months of the war was largely due to the "roll-up" plan of the Far East Command which had been in effect for some time before the outbreak of hostilities.

[26] To meet part of the requirements, the US command contracted Japanese manufacturers in August to produce 68,000 vehicles for the ROK Army, mostly cargo and dump trucks, with first deliveries to be made in September.

[29] From the outset, high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) ammunition was particularly scarce, but this changed as US and Japanese manufacturers increased production to meet wartime needs,[30] as a part of the Far East Command's "Operation Rebuild".

Often the cooked rice, made into balls and wrapped in cabbage leaves, was sour when it reached the combat troops on the line, and frequently it did not arrive at all.

One route left from McChord Air Force Base in Tacoma, Washington, and transited through Anchorage, Alaska, and Shemya in the Aleutians before finishing at Tokyo.

This departed from Travis Air Force Base near San Francisco, California, and passed through Honolulu and Wake Island before arriving in Tokyo; the trip was 6,718 miles (10,812 km) and took 34 hours to complete.

A third route was from California through Honolulu, and Johnston, Kwajalein, and Guam Islands to Tokyo: a distance of about 8,000 miles (13,000 km) and a flying time of 40 hours.

[28] The consumption of aviation gasoline during combat and resupply operations was so great in the early phase of the war, taxing the very limited supply available in the Far East, that it became one of the more serious logistical problems facing UN planners.

On a number of occasions throughout the war, the demand of military consumption had the effect of leaving Japanese gas stations with no fuel to sell to the public.

[52] Even the best of them were narrow, poorly drained, and surfaced only with gravel or rocks broken laboriously by hand, and worked into the dirt roadbed by the traffic passing over.

[27] Since the Korean railroads had been built by Japan, repair and replacement items could be borrowed from the Japanese National Railways and airlifted to Korea within a very short time after the need for them became known.

The most successful guerrilla attack behind the lines of the Pusan Perimeter occurred on August 11 against a VHF radio relay station on Hill 915, 8 miles (13 km) south of Taegu.

[56] In mid-July, the UN Far East Air Force (FEAF) Bomber Command began a steady and increasing attack on strategic North Korean logistics targets behind the front lines.

The great bulk of Soviet supplies for North Korea in the early part of the war came in at Wonsan, and from the beginning it was considered a major military target.

Three days later, 30 B-29 bombers struck the railroad marshaling yards at Seoul, another major staging area for North Korean supplies.

In the meantime, carrier-based planes from the USS Valley Forge, which was operating in the Yellow Sea, destroyed six locomotives, exploded 18 cars of a 33-car train, and damaged a combination highway and rail bridge at Haeju on July 22.

This interdiction program, if effectively executed, would slow and perhaps critically disrupt the movement of North Korean supplies along the main routes south to the battlefront.

[31] North Korea's lack of large airstrips and aircraft meant it conducted only minimal air resupply, mostly critical items being imported from China.

[51] The North Koreans tried on several occasions to resupply their units by sea or conduct amphibious operations at the outbreak of the war but each time were decisively defeated.

It also had several crucial connection points to the Soviet Union and China, but it was not designed for military traffic and the weather conditions made travel on the roads difficult.

This method of attack seems to have caused such heavy casualties among the North Korean labor force trying to keep the pontoons in repair that they finally abandoned the effort.

[69] By September 1 the food situation was so bad in the North Korean Army at the front that most of the soldiers showed a loss of stamina with resulting impaired combat effectiveness.

[56] The North Koreans' communications and supply were not capable of exploiting a breakthrough and of supporting a continuing attack in the face of massive air, armor, and artillery fire that could be concentrated against its troops at critical points.

[71] Several units lost crucially needed supply lines in the middle of their offensives, particularly when crossing the Naktong River which had few stable bridges remaining.

The NK 3rd Division stopped receiving food and ammunition supply as it pushed on Taegu in mid-August, forcing one of its regiments to withdraw from the captured Triangulation Hill.

[72] At Naktong Bulge, the NK 4th Division was able to establish a raft system for moving supplies across the river, but it still suffered serious food, ammunition, weapon, and equipment shortages after its August 5 crossing.

[69] Historians contend that for the UN and North Korea, locked in a bitter battle where neither could gain the upper hand, logistics was among the most important determining factors in how the war would progress.

[58] As the disparity in logistics capability widened between the UN and North Korean forces, the well-supported UN troops were able to hold their positions along the Pusan Perimeter, while the morale and the fighting quality of NKPA deteriorated as resupplies became increasingly unreliable.

[71] North Korean logistical inefficiency prevented them from overwhelming UN units in the Pusan Perimeter and enabled the defending UN troops to hold on long enough for a counterattack to be launched at Inchon.